The Black Panther: A Comic Book History

The late 1960s was a tumultuous time for America both domestically and abroad. The events taking place outside U.S. shores, such as the Vietnam conflict, began to affect domestic unrest in already existing social movements, most notably the Civil Rights Movement. Although President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law on August 6, 1965, which banned discriminating voting policies, just five days later, riots broke out in Watts, a section of Los Angeles, centered around police brutality toward African Americans. Times were indeed tense, and the issues of race were at the forefront. The fires that burned in Southern California were not solely about one incident per se, but a response to continued systematic oppression. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who, by this time, was venturing outside of the Jim Crow South to address poverty in America’s ghettos in urban centers like Chicago and Los Angeles, called the emerging riots the “language of the unheard.”[1]

The larger implications of socioeconomic inequality were now part of a larger critique of what America was and was not. This was the backdrop that Marvel Comics’ Stan Lee and Jack Kirby used to create their new character, Black Panther. The character’s alter ego, King T’Challa, was ruler of the fictional African kingdom of Wakanda. He was the first black superhero to debut in American comic books.

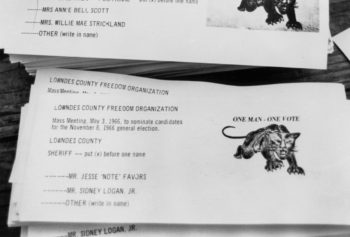

Originally conceived of as the “Coal Tiger,” Black Panther cannot be separated from the times in which he burst onto the comic book scene in Fantastic Four #52 in July of 1966. Prior to the release of the comic, Lee and Kirby, according to writer Sean Howe, were very much aware and influenced by an article in The New York Times that discussed the formation of the Lowndes Country Freedom Organization (LCFO), which had as their emblem a black panther.[2] Howe attributed that article as the impetus for changing the name of the character that Lee and Kirby had been working on for months.

The media referred to the LCFO as “The Black Panther Party,” after its formation in 1965 under the direction of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) field secretary, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture). Carmichael believed that African Americans’ political power resided in the will and political self determination of local people.[3] This was his organizing principal for the voter registration work that he was engaged in. However, that was easier said than done. “Bloody Lowndes,” as it was commonly known then, earned that unflattering nickname from decades of violence and terror inflicted on African Americans to disenfranchise them. To have a clearer understanding of just how dire things were in 1965, we must grasp the fact that no African American had successfully registered to vote there in over sixty years. Additionally, 86 white families owned 90 percent of the land.[4]

Today animal symbols readily associated with political parties are the donkey and elephant. In Alabama, election laws required that political parties have a unique symbol. John Hulett, Sr., a local leader in Lowndes Country during the time, explained that African Americans felt like their backs were pushed against the wall socio-politically and metaphorically they believed that they would respond like a cornered panther to take control of their political fate. Thus, the black panther embodied both identity and strength as members of the party sought to vote for their elected officials—nominees that came from their community, which was 80% African American at the time. The LFCO mascot did not just inspire Lee and Kirby, but it also inspired the formation of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense in Oakland, California in October of 1966. Given this historical context, it is hard to see how the Marvel character could be viewed as anything other than inherently political.

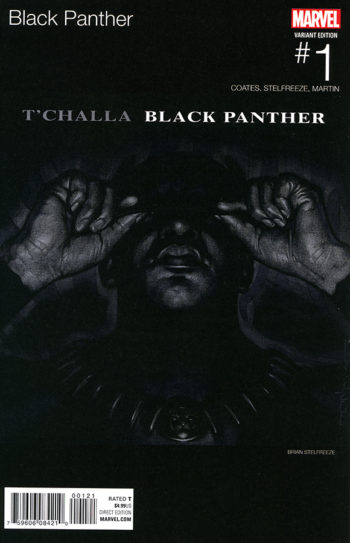

When interviewed about Black Panther, a year before the recent film was released, Stan Lee seemed to downplay the political import with a normalizing attitude toward diverse representation in the artistic medium. “It wasn’t a huge deal to me,” he confessed, “A good many of our people here in America are not white. You’ve got to recognize that you’ve got to include them in whatever you do.”[5] So it could be argued that with the Black Panther character, Lee and Kirby were attempting to chip away at the intolerance in comics by introducing T’Challa to American audiences. The film based on the comic has enjoyed tremendous success, and as such, questions of cultural impact have been part of the conversations about the character and the film. Many journalists, cultural critics, and scholars have chimed in about what Black Panther means for American popular culture if anything. In her essay, “And All Our Past Decades Have Seen Revolutions,” Rebecca Wanzo, Associate Professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Washington University in St. Louis, maintained, “If we recognize that representation matters, and that Black representation has been a tool in white supremacy, tracing the character over decades illustrates an epic struggle to make a “real” Black character out of something that was a white fantasy of blackness.”[6]

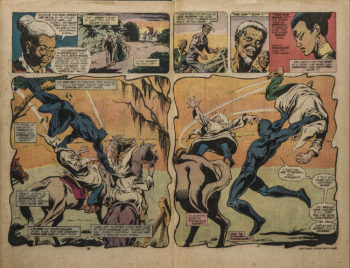

Making sense of that very “struggle” for representation is exactly one of the subjects the latest Special Collection exhibit in Olin Library attempts to convey. The goal of the exhibit is not to give critical commentary, but rather to highlight the way the character has changed over the decades. The exhibition starts with 1966 to the most recent iteration of the character. This allows visitors and patrons to see the evolution of Black Panther starting from the Lee and Kirby era to the most contemporary rendition by Ta-Nehisi Coates and Brian Stelfreeze. This exhibit was curated by Skye Lacerte, curator of the Modern Graphic History Library, and Vernon Mitchell, Jr., Curator of Popular American Arts and Culture. Their exhibit focuses on the art of Black Panther by highlighting comic book covers and spreads that they believe give some insight into the way the character changes over the last fifty-two years. The comic books used in this exhibition are from the Center for the Humanities Comics Collection, transferred to the DB Dowd Modern Graphic History Library in 2012.

Typically, we do not tend to associate comic books with libraries, but we absolutely should. Black Panther gives the library the opportunity to reach different audiences and also expose this particular genre of book to those that may undervalue its contribution or be unfamiliar with the work. “Comics reveal a great deal about our varying identities,” mentioned Lacerte, when asked why comic books and graphic novels should be available in libraries. “Comic book characters,” she went on to say, “are something people can see themselves in and it helps people feel like they belong or have someone on their side. Comics can also teach us about ourselves (in the present) and then teach others about people in the past.” Other University Library staff, such as Garth Reese, (former) Head of Curation, asserted that comic books also give us a view into material culture as well. “Comic books today are printed and produced with better materials and technology than just a decade ago. They also can give glimpses into popular culture that traditional literature can never reveal.”

The Black Panther comic book exhibit can teach us a great deal about the medium and its larger impact on society or vice versa. The character, Black Panther, was born out of the cultural and social revolutions of the 1960s, and what impact and meaning that has on our understanding of the series and subsequent characters is left to the visitors, patrons, and scholars. However, what better time to talk about comics and their influence in popular culture than at this very moment, when the superhero film genre is arguably at its apex?

[1] Martin Luther King, Jr., “The Other America,” (speech) Grosse Pointe High School, 14 March 1968.

[2] Sean Howe, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story (New York: HarperCollins, 2012), 32, 33. “Negroes Lose Fight to Oust All Officers in Lowndes County,” The New York Times, 1 April 1966; John Corry “The Changing Times IN Lowndes County: An All-Negro Ticket; The Changing Times in Alabama: All Negro Ticket,” The New York Times, 31 October 1966.

[3] Peniel Joseph, Stokely: A Life, (New York: Basic Civitas, 2014), 87.

[4] Rebecca Woodham, “Lowndes County Freedom Organization,” Encyclopedia of Alabama http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-1781 (Accessed 14 May 2018).

[5] Joshua Ostroff, “Marvel Comics Icon Stan Lee Talks Superhero Diversity And Creating Black Panther,” Huffpost, 9 September 2016. https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2016/09/01/stan-lee-marvel-superhero-diversity_n_11198460.html Accessed 8 May 2018.

[6] Rebecca Wanzo, “And All Our Past Decades Have Seen Revolutions: The Long Decolonization of Black Panther” The Black Scholar, 19 February 2018.