Don’t Call Her Shirley: My Month in WashU’s Digitization Unit

In a basement on West Campus, a mile away from Washington University’s Danforth idyll, sits The Shirley. The beating heart of the University Libraries’ Preservation and Digitization unit, a definite article always precedes the name in a tribute befitting its technical grandeur and considerable capabilities. The Shirley observes the world through a 150-megapixel large-format camera mounted on a 40” x 60” Titan copy stand flanked by radiant LED lights, an Olympian arrangement that captures cultural heritage objects in stunning detail. From paintings and oversized scrapbooks to simple paper documents and photographs, The Shirley handles it all, transforming fragile physical materials into pristine digital representations that stand the test of time.

I have been privileged to work with The Shirley for a little over a month as part of a practicum through the University of Missouri, where I am in the master’s program for library and information science with an emphasis in archival studies. A lifelong St. Louisan, I chose WashU as my practicum site because I figured they would have some nice equipment on hand. And folks, let me tell you, your fine school did not disappoint. The digitization unit possesses several substantial machines, such as the BC-100, a dual-camera high-resolution book scanning system that ably captures tomes and tracts swiftly and safely. Still, The Shirley is the shining star, the result of a $100,000 gift from James and Joan Schiele in honor of former Vice Chancellor of Scholarly Resources and Dean of University Libraries Shirley K. Baker.

Capturing images on The Shirley is like climbing to the top of the Statue of Liberty: there are a lot of steps involved, but it gives you an inside view of history that few people are fortunate to see. The ascent begins by assessing the environment around the machine: Is the lighting uniform and unobstructed? Have you sufficiently shaken the dust off the velvet duvet upon which the archival objects rest? In fact, what do the materials you’re about to shoot look like? Anything weird in there? Are any photos all curled and wonky? Do you have enough micro-spatulas and little bean bags to weigh the images down when the time comes?

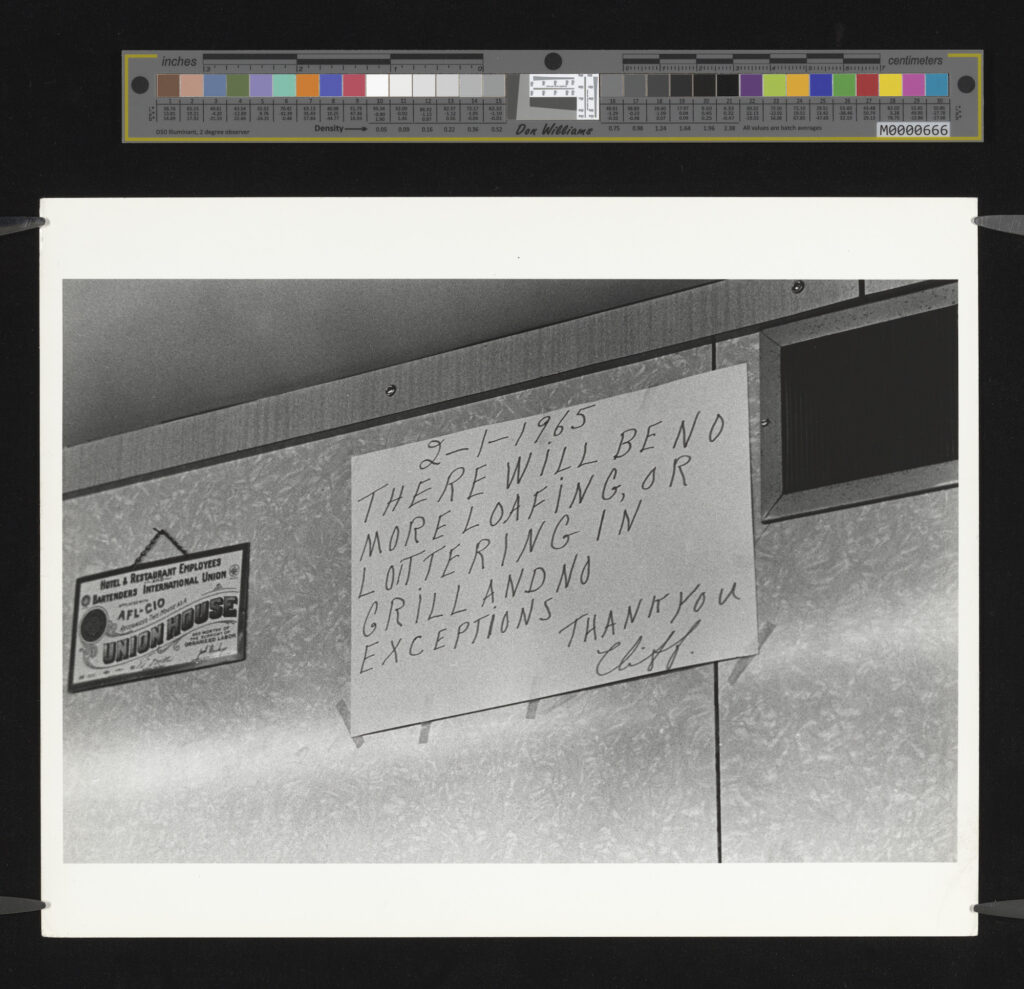

All this fancy hardware is matched by equally fancy software, in this case, the mighty Capture One, a photography suite that controls nearly every aspect of the digital imaging process. Each new session starts by importing the correct LCC, a “lens cast calibration” tool that ensures light falls evenly across all captured images. A corresponding “target image” also saunters into the session at this step, providing an essential reference point for verifying consistency in color balance and exposure. The photographic values in an image can be compared to the tactile targets that are captured alongside each physical object, as demonstrated in the photo above. This makes life much easier for the splendid staff in the digitization unit, who would be stuck eyeballing each image to determine crucial qualities if they did not have the aid of targets.

Next up, the camera needs to be focused and calibrated to the right PPI for the job. Photographs shot on The Shirley typically clock in at 600 PPI, or “pixels per inch.” Shooting at a high PPI can unveil details in images that are difficult to perceive with the human eye but become clear as day when they are enhanced, Blade Runner style. For example, Blewett Hall is currently home to faculty offices for WashU’s music department. As the picture below shows, though, in 1955 the building played host to an unexpected houseguest in the form of fire. Holding this photo in my hands, I could tell by the illumination of the smoke that something was amiss but I couldn’t quite make out the details. Was the building ablaze, or simply caught in the misty morning sun? Thankfully, shooting the image on The Shirley unveiled key characteristics, like ladders stacked against the building as well as two intrepid firemen hoisting a hose to one of the upper windows. Given that Blewett Hall is still standing strong on Forsyth Boulevard, I’d say those fellas did their job.

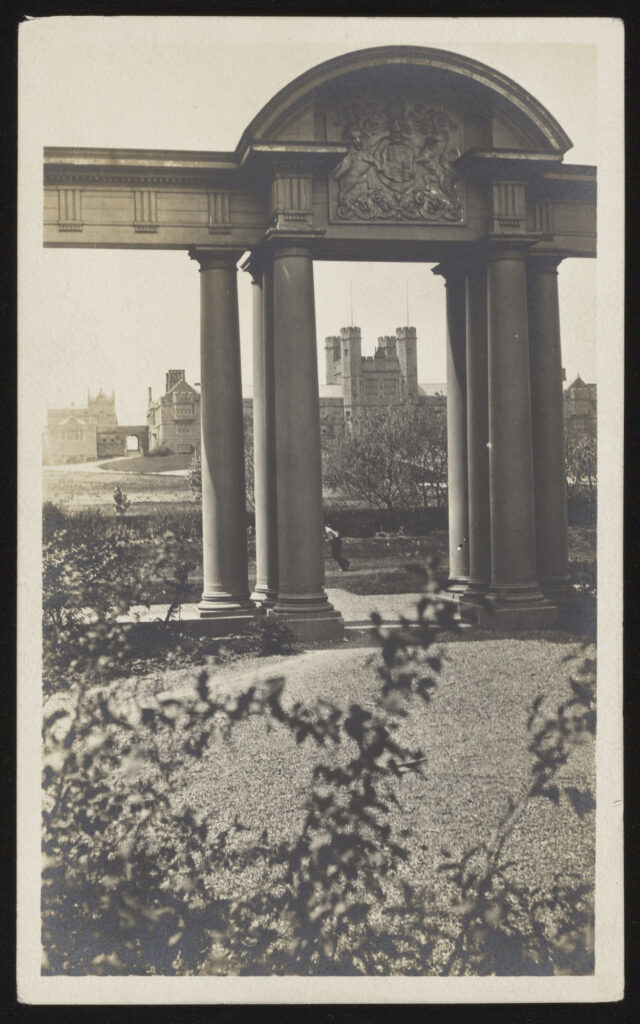

As fascinating as I find this fifties inferno to be, however, it’s not my favorite photo that I digitized in my brief time at WashU. That honor goes to the columned arch on the right, a Doric triumph that once stood next to the British Pavilion Building, purchased by the university after the World’s Fair to house the art department until it was demolished to build Bixby Hall in the 1920s. I’m naturally drawn to neoclassical stuff like this, but that’s not why I love this photo. When you hold this 3.5” by 5.5” picture in your hand, the arch framing a distant Brookings Hall appears to be the most prominent subject. But if you digitize this tiny photo on a state-of-the-art imaging system that allows you to witness the scene in high resolution, you can zoom into the base of the left bank of columns to discover an individual almost certainly tripping and falling to the ground. This pic was snapped way back in 1908, and it’s possible that not even the photographer noticed when this person lost their fight with gravity. Yet here we are, 115 years later, permitted by The Shirley to wonder about this long-deceased individual.

These digitized images provide glimpses into history, literal snapshots from the past that roar back to glorious life through the diligent work of the Preservation and Digitization unit. I found my month in the department to be endlessly fascinating as I learned how to capture high-quality photos that I then processed into archival and access copies for current and future use. I also prepared metadata that will help with discovery down the line, although I was not allowed to use the phrase “Man eats it in front of arch” as the title for the image above. C’est la vie.

If you are at all interested in history, archival preservation, or just looking at pictures of old buildings and people, I can’t recommend enough that you reach out or take a tour of the digitization unit. Along with student worker or work-study programs that will give you experience with The Shirley and with Capture One, you can also place requests for materials in the university’s collections to be digitized both for academic and personal projects. (Be sure to contact a curator or the librarian in charge of the collection you want to have digitized; they’ll help you get set up.) I know of one student who requested a bunch of digitized photos for a series of short documentaries, just one of many ways that you can take advantage of the immense digitization capabilities on offer at your school. So get to know The Shirley, and see Washington University in ways you never expected.

Mike McHugh is a current graduate student in the University of Missouri’s Library and Information Science program. He recently completed a 90-hour practicum, supervised by Mitch Sumner, with the Digitization unit.