Emmett Till: What Were We Seeing Then, What Are We Saying Now?

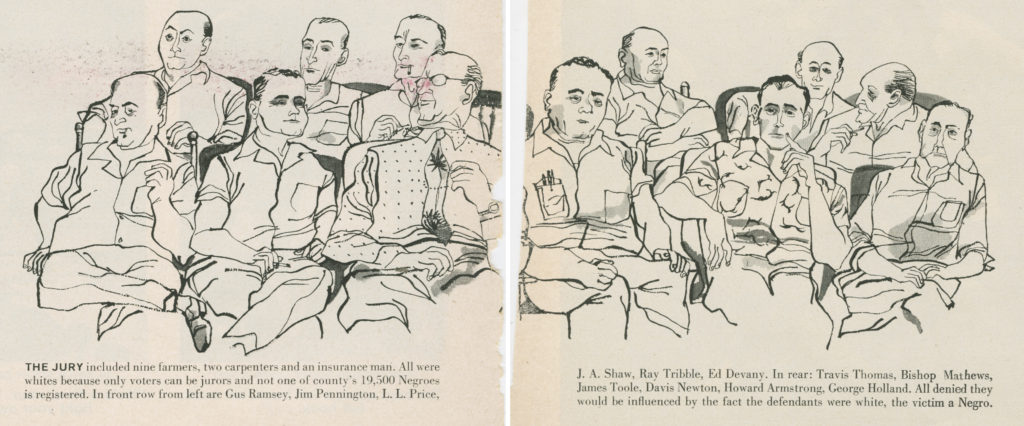

October 3, 1955: Life publishes Frank McMahon’s illustrations from the trial of Emmett Till’s murderers. Often considered the full igniting spark of the civil rights movement, Till’s lynching continues to provoke conversations surrounding race relations in the United States today. The conversation around Emmett Till and his representation in the American public’s imagination began with what has been described as a “sham trial” of an all-white, male jury, and continued when Jet magazine published images of Till’s brutally disfigured face at his mother’s urging, forcing the public to confront the violence of American racism in September of 1955 (1).

It was revived in 2007 when “the woman at the center of the case, Carolyn Bryant Donham, recanted her original testimony in an interview with the historian Timothy Tyson, admitting that Mr. Till never made advances toward her” (2).

In 2012 with the shooting of Trayvon Martin.

In 2014 with the shootings of Michael Brown and Tamir Rice.

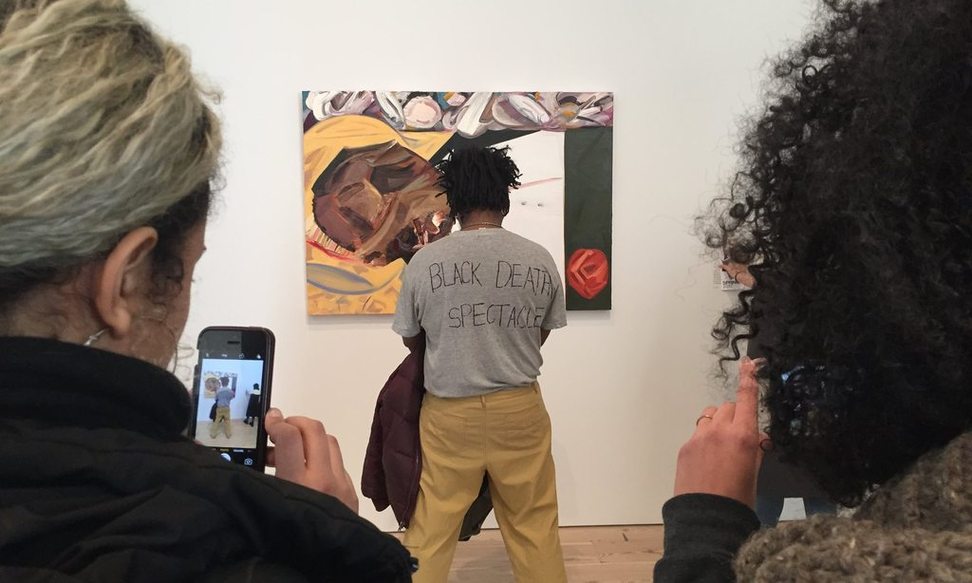

Till’s very image was at the center of the conversation around representations of violence against black and brown bodies in the context of the Black Lives Matter movement when the Whitney Biennial included an artistic interpretation of his open-casket images produced by white artist, Dana Schutz.

Parker Bright, a black artist, conducted peaceful protests by standing in front of the painting, partly blocking the view of the painting wearing a T-shirt that reads “Black Death Spectacle” on the back (3). Other artists joined the protests.

“’The subject matter is not Schutz’s,’ Ms. Black [a fellow black artist] wrote in a Facebook message that has been signed by more than 30 other artists she identifies as nonwhite. ‘White free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go.’ She added that ‘contemporary art is a fundamentally white supremacist institution despite all our nice friends’” (4).

“Representation in art is an arena of conflict and confrontation for Black people,” Sharpe says. “Dana Schutz walked into that, and what we’re seeing are vigorous responses.” As for the protesters, she adds, they are “keeping watch with the dead, practicing a kind of care” (5).

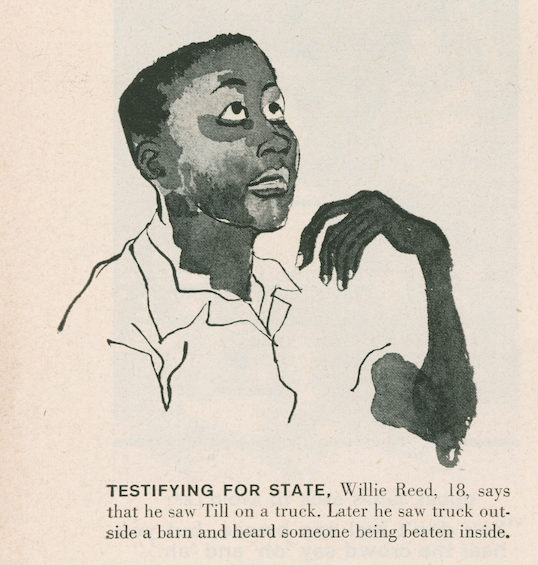

Testifying for State: Willie Reed, 18, says that he saw Till on a truck. Later he saw truck outside a barn and heard someone being beaten inside.” Life, 3 October 1955, p. 36, illustrated by Frank McMahon.

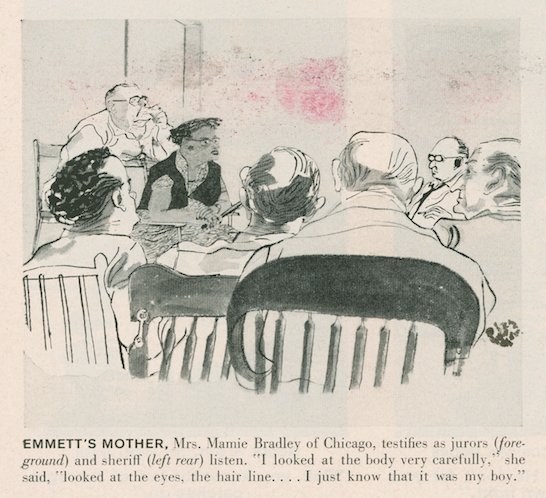

Emmett’s Mother “Mrs. Mamie Bradley of Chicago, testifies as jurors…and sheriff…listen, ‘I looked at the body very carefully,’ she said, ‘looked at the eyes, the hair line…I just know that it was my boy.’” Life, 3 October 1955, p. 36, illustrated by Frank McMahon.

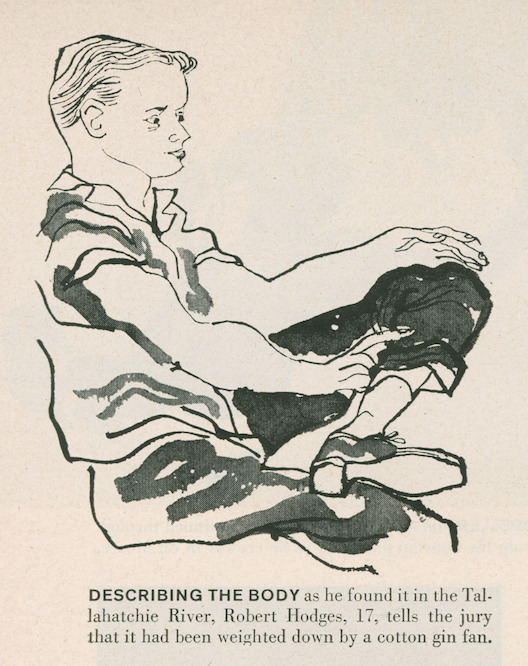

“Describing the body as he found it in the Tallahatchie River, Robert Hodges, 17, tells the jury that it had been weighted down by a cotton gin fan.” Life, 3 October 1955, p. 36, illustrated by Frank McMahon.

It is significant that these illustrations were published in Life, traditionally a wholesome magazine published for the white masses. The accompanying text demonstrates an intended angle on the story, calling out the injustice of the case and demanding Life’s white readership confront the realities of the criminal justice system at the time, a task which our current mass media continues to demand (however successfully) of the American public.

Sources

- Berger, Maurice. “The Lasting Power of Emmett Till’s Image.” The New York Times 5 (2017). https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/04/05/controversy-contexts-using-emmett-tills-image/

- Berger, Maurice. “The Lasting Power of Emmett Till’s Image.” The New York Times 5 (2017). https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2017/04/05/controversy-contexts-using-emmett-tills-image/

- Kennedy, Randy. “White Artist’s Painting of Emmett Till at Whitney Biennial Draws Protests.” The New York Times 21 (2017). https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/21/arts/design/painting-of-emmett-till-at-whitney-biennial-draws-protests.html

- Kennedy, Randy. “White Artist’s Painting of Emmett Till at Whitney Biennial Draws Protests.” The New York Times 21 (2017). https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/21/arts/design/painting-of-emmett-till-at-whitney-biennial-draws-protests.html

- Mitter, Siddhartha, and Christina Sharpe. “‘What Does It Mean to Be Black and Look at This?’A Scholar Reflects on the Dana Schutz Controversy.” Art, Interview. Hyperallergic. http://hyperallergic. com (2017). https://hyperallergic.com/368012/what-does-it-mean-to-be-black-and-look-at-this-a-scholar-reflects-on-the-dana-schutz-controversy/

Images from Life are part of the Walt Reed Illustration Archive at the Dowd Modern Graphic History Library.