Connecting Contexts: The Modern Literature Collection and The Letters of Samuel Beckett

We are pleased to present Connecting Contexts: The Modern Literature Collection and The Letters of Samuel Beckett, a new digital exhibit that connects one of the world’s major Beckett research collections with the authoritative, multi-volume set of his published correspondence.

The sections of the digital exhibit reflect the cases and iPad station in the onsite exhibit of the same name. The colloquium What is the Word: Celebrating Samuel Beckett, which Washington University hosted in November 2019, is also represented, with videos from six of the sessions and links to further information on that multifaceted event.

The exhibit’s contents were drawn from the Modern Literature Collection (MLC) and were selected by MLC Curator Joel Minor to coincide with the timelines and other content provided by Lois Overbeck, who is co-editor of The Letters of Samuel Beckett and director of the Letters of Samuel Beckett Project at Emory University. The four timelines covering the 60 years of Beckett’s writing life, reflect the volumes of The Letters of Samuel Beckett (LOSB).

In addition to the timelines, Overbeck provided graphics for posters that were incorporated as cases: Friends on the Radical Fringe which profiles those individuals most important to Beckett’s formative years as a published writer; and Actors in Beckett’s Plays which profiles six of the most important actors to Beckett and his work during the three decades he wrote and directed plays. As with the timeline cases, Minor selected items to coincide with the works mentioned in both the Friends and Actors cases.

Both Overbeck and Minor found relevant quotes from the corresponding volumes of The Letters of Samuel Beckett to go with some of the contents and their labels in the onsite exhibit. The digital exhibit includes a quote to go with each item, further solidifying the connection between the object and the letter. Following are some examples of these pairings.

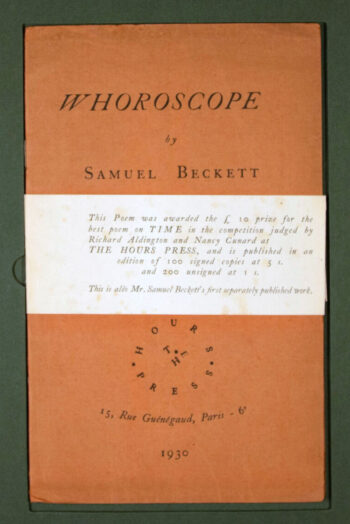

Beckett’s first separate publication was a hastily written and submitted entry into Hours Press’ contest for a poem on the subject of time. We have one of the 100 signed copies of Whoroscope, and include with it an excerpt from publisher Nancy Cunard writing to Louise Morgan that the poem was so good it needed to be printed on its own.

An inscribed, first edition of Beckett’s first novel, Murphy, is presented with an impassioned and sarcastic passage from a November 13, 1936, letter to publisher George Reavey, objecting to the notion of cutting anything from the book in order to get it published in the United States.

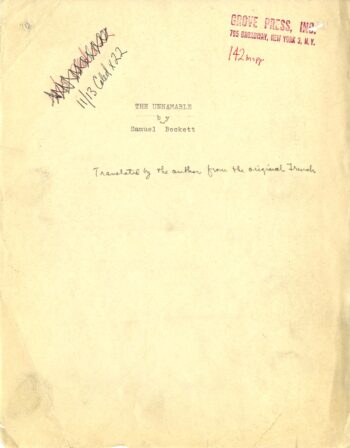

After Beckett started writing and publishing in French, he had to figure out how to satisfactorily translate his absurdist texts into English. As a January 4, 1956, letter to Cyril Lucas shows, in regard to translating his novel L’Innommable, he had found that it would be far easier for him to translate his own works rather than trying to fix what other translators attempted to do. We include an excerpt from this letter with scans from his self-translation typescript, called The Unnamable in English.

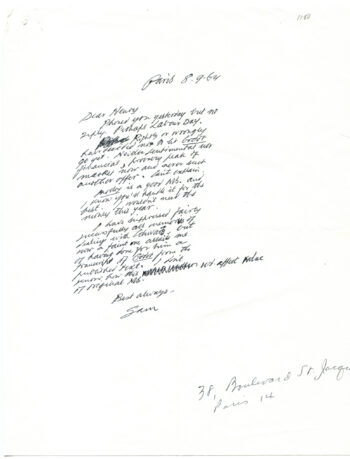

One item in the exhibit directly connects Beckett’s manuscripts and correspondence with The Letters of Samual Beckett and the Modern Literature Collection: a September 8, 1964 note to book and manuscript dealer, Henry Wenning. The short letter shows how Beckett had become close to Wenning and trusted him to sell his manuscripts. It is one of 92 pieces of correspondence from Beckett to Wenning in the Samuel Beckett Papers. Wenning was the source of all our Beckett manuscripts in the mid-60s to early 70s, and this letter is included in Volume 2 of The Letters of Samual Beckett.

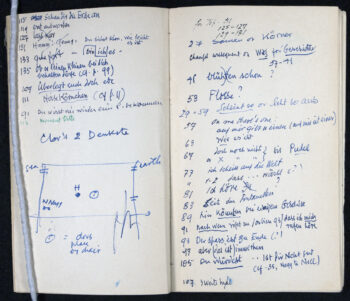

Beckett’s personal copy of Warten aüf Godot, which he used when called to Berlin to consult on a German production of his breakthrough play, En attendant Godot (Waiting for Godot), in February 1965, is extensively corrected and annotated in Beckett’s hand. The quote from an February 8 letter to Barbara Bray shows just how frazzled Beckett felt by the poor state of the rehearsals.

Another personal copy of a book used and annotated by Beckett for a German production of his play (his directorial debut in German) is the bilingual Endspiel – Fin de partie. This book brings out a letter that tells a very different story about a different production. In an August 27, 1967, letter to Avigdor Arikha and Anne Atik, Beckett expresses how pleasantly surprised he is to be enjoying himself in Berlin this time and how well rehearsals for Endspiel (Endgame) are going.

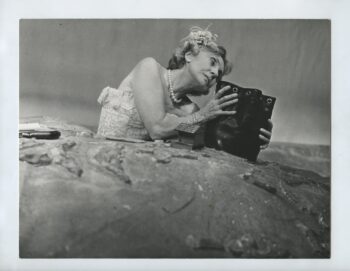

Classically trained French actress Madeleine Renaud was very popular in her native country when she took on the role of Winnie in Oh les beaux jours (Happy Days). We included three artifacts from this unlikely but very successful pairing: an original production still, a playbill, and an LP of excerpts. Beckett may have initially had misgivings over Renaud playing Winnie, but as his November 1, 1963, note to the actress shows, he was deeply moved by her portrayal, just as much as critics and audiences were.

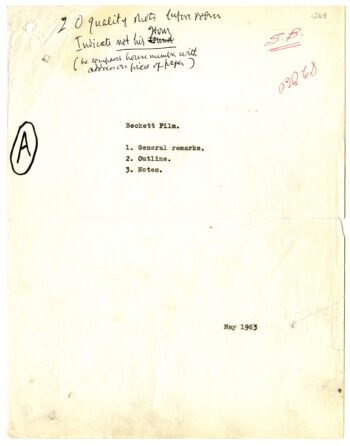

We also have a few examples of what we hold related to Beckett’s only foray into film, including a corrected carbon typescript draft. We present this with excerpts from an April 13, 1963, letter to Barney Rosset of Grove Press, in which Beckett describes his initial ideas for what would become known simply as Film, starring Buster Keaton.

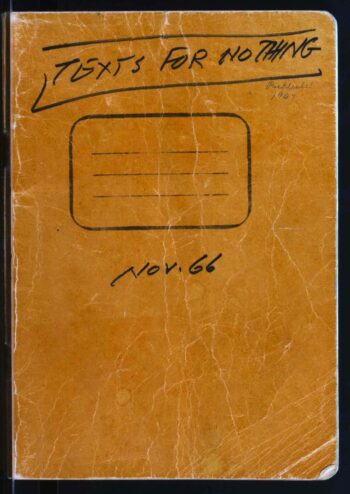

The Samuel Beckett Papers contain nine notebooks the author used for first or early drafts of his prose and short radio or television plays, from the mid-1960s. Some of these were used for his auto-translations, including Texts for Nothing, originally written as Textes pour rien. The notebook shows Beckett’s struggle with translating the work, as does the short excerpt from a December 1, 1966, letter to his good friends Avigdor Arikha and Anne Atik saying “it’s rather knocked me silly.”

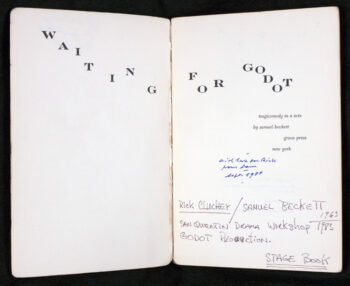

One of our most exciting acquisitions in recent years was the Rick Cluchey Collection of Waiting for Godot Materials, which includes two prompt books from productions Beckett assisted with. Both books are heavily highlighted and excised, showing how much Beckett continued to revise his work. With the book for the 1975 production we excerpt a January 19 letter to Jocelyn Hebert, expressing his desire to get out of directing.

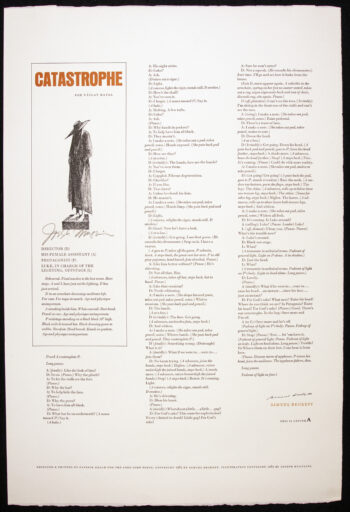

For the fine-press broadside edition of Catastrophe, Beckett’s only dramatic foray into politics (albeit still in a Beckettian manner), to benefit the imprisoned Czech writer Václav Havel, we included the entire text of a letter from Havel to Beckett after Havel was released from prison. The letter expresses his deep gratitude for Beckett’s play, how much it helped get him through his time in prison, and Beckett’s influence on his own writing.

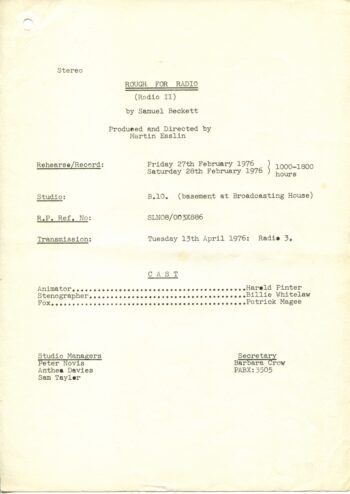

With an actor’s script for Rough for Radio II, we include a letter from Beckett to the director Martin Esslin answering questions related to the sound effects. The production was the English-language premiere and starred Harold Pinter, Billie Whitelaw, and Patrick Magee, for a BBC broadcast on the occasion of Beckett’s 70th birthday celebration.

There are many more scans and excerpts to discover in Connecting Contexts, which we hope will help illuminate the extraordinary life and work of Samuel Beckett, for both scholar and casual fan alike. To find more of our Beckett resources in Special Collections, see our Introductions to Selected Authors & Their Collections.

Lastly, we are also launching a companion digital exhibit, “If you could finish it…” also based on an onsite exhibit, which focuses on Beckett’s auto-translations.