“Lunacy and Organization” in the William Gaddis Papers, Part 3

In celebration of the new editions of William Gaddis’s first two novels, The Recognitions and J R, both published by NYRB Classics, we are exploring the origins of the books in the William Gaddis Papers. Read Part 1 and Part 2 of this series. The following is the third and final part.

In my 15 years of working with authors’ literary papers, I have seen a wide range of “lunacy and organization” to incoming collections. While I was not involved in the acquisition or processing of the William Gaddis Papers, I can tell by working with them today that it would have been impractical for library staff (or the appraiser who handled the papers first) to sort everything by format, subject, or other manner before making the collection available to researchers.

More importantly, moving contents around would have violated the papers’ original order, which, as I mentioned in Part 1 of this series, is vital to maintain as much as possible in order to better understand the creative process behind the work being studied.

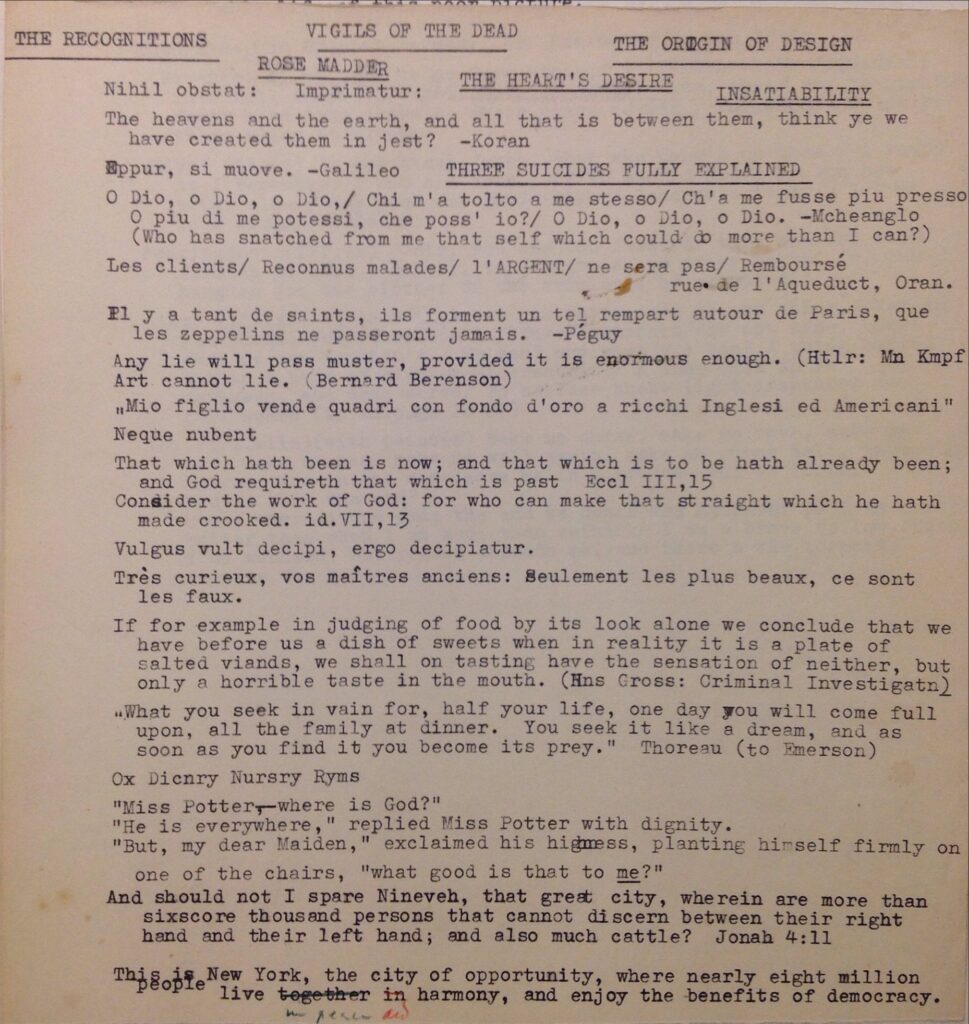

So, for the most part, how Gaddis filed his papers is how the researchers find them as they dig around for their own better understanding of the work. At first glance, the papers may look cluttered, dense, intimidating—much like J R or The Recognitions do at first to many—but they are also an invitation to individual discovery and connectivity, again, much like the books themselves.

Thanks in large part to Crystal Alberts, associate professor of English at the University of North Dakota, who was the first scholar to work with the papers when they arrived in March 2002, we can read about the process behind the acquisition of the William Gaddis Papers in the finding aid itself (click on the “Additional Description” tab). This is a level of detail one typically does not find in a finding aid, but warranted in the case of an author whose work is so meticulously studied as Gaddis’s.

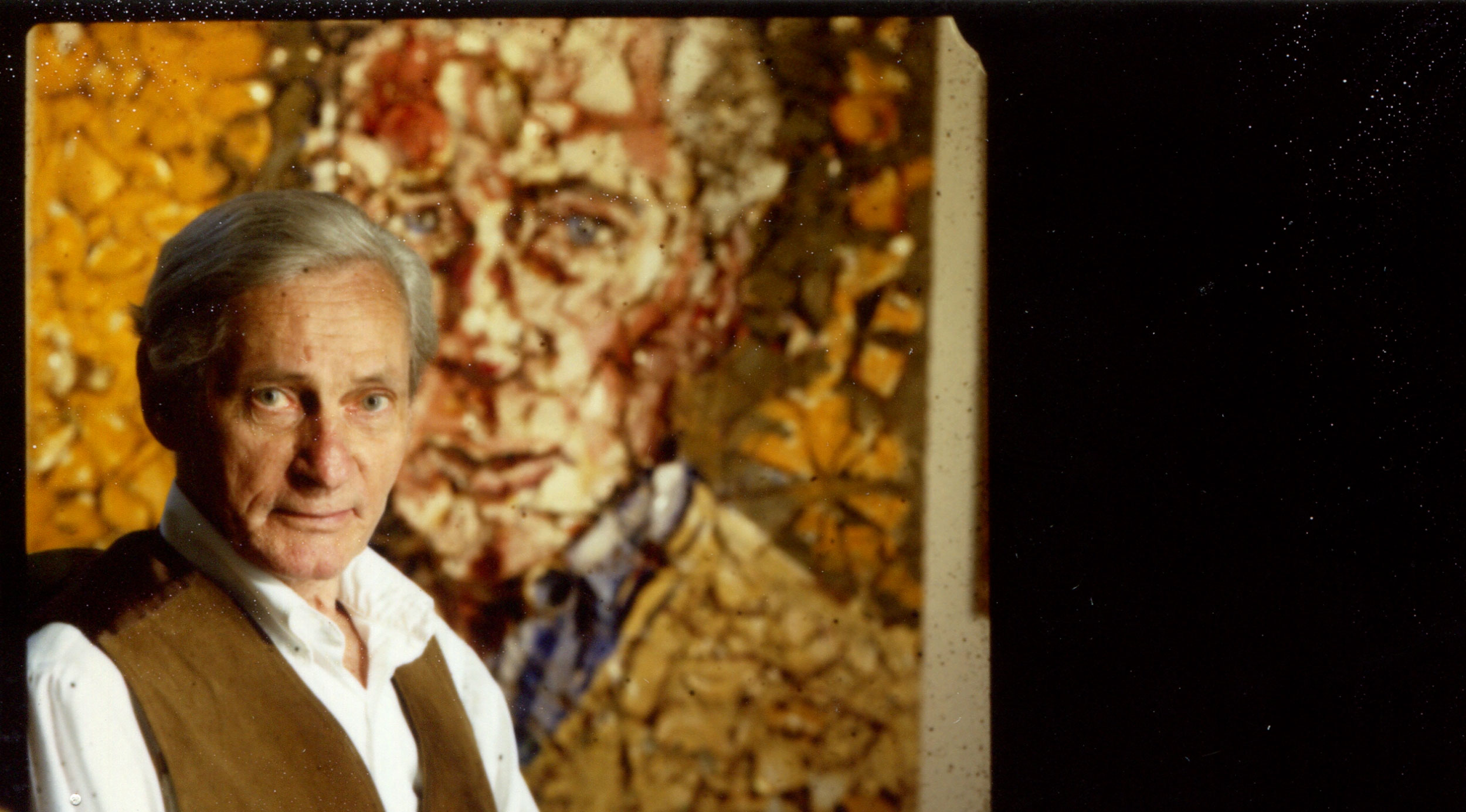

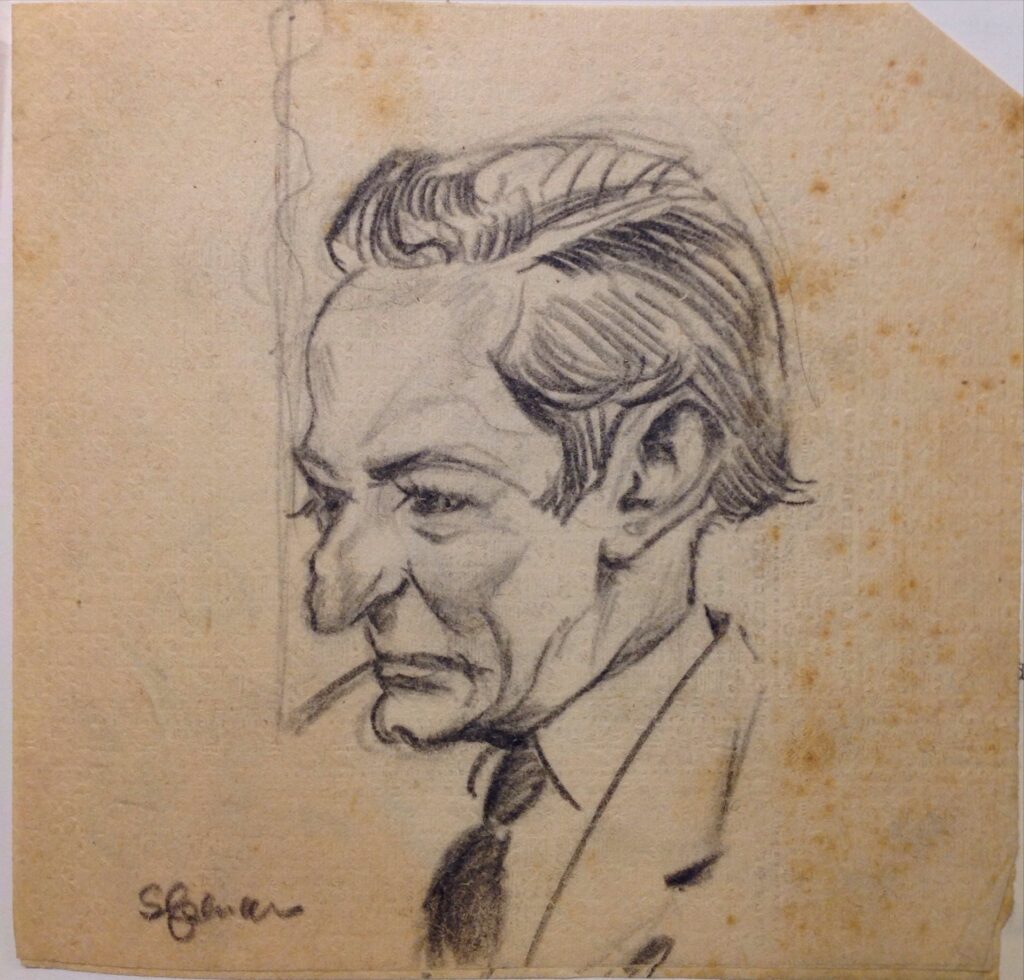

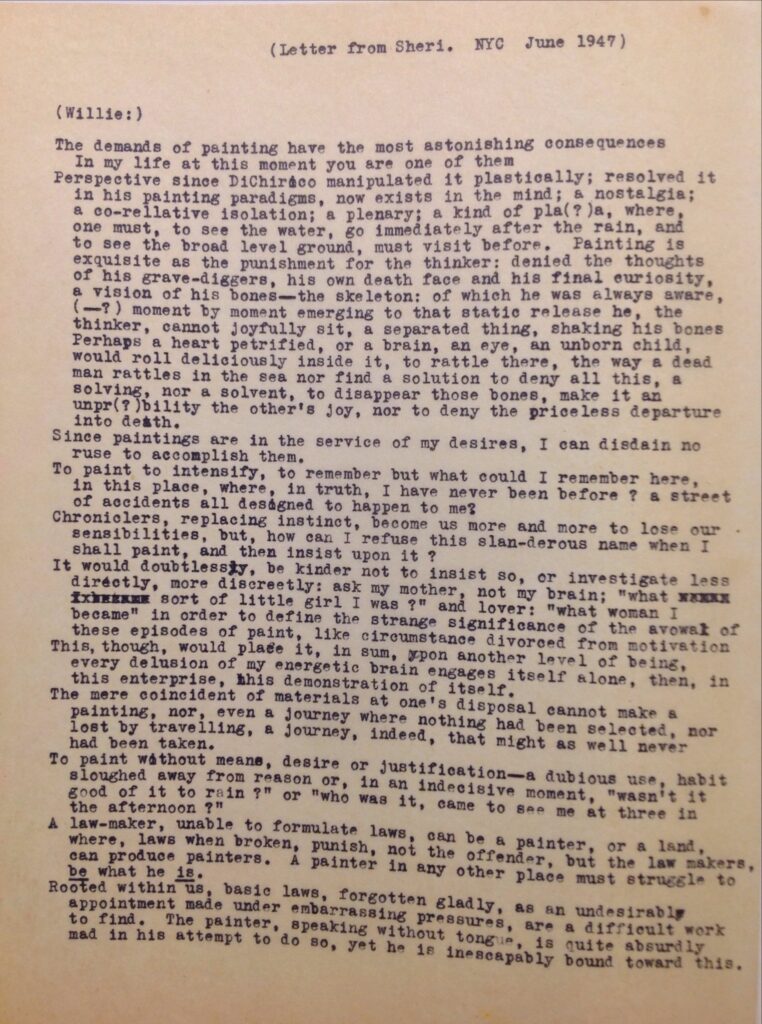

Alberts wrote two scholarly articles centered on the William Gaddis Papers and his first novel, The Recognitions. In “Valuable Dregs: William Gaddis, the Life of an Artist” (Paper Empire: William Gaddis and the World System, 2007), Alberts explores the archive’s physical order and how a writer as guarded of his personal life as Gaddis was, who wanted to keep it separate from his work, left us an archive where the two inevitably interact.

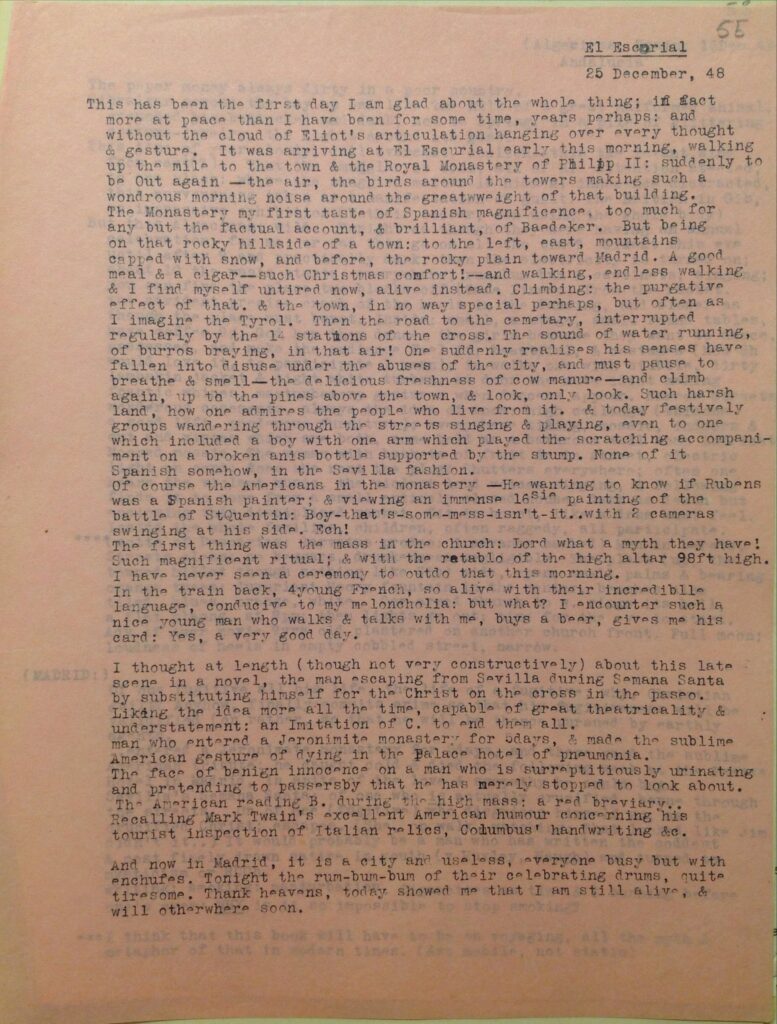

In “Mapping William Gaddis: The Man, The Recognitions and His Time” (William Gaddis, “The Last of Something,” 2010), Alberts compares excerpts from the travel journal Gaddis used in Spain with excerpts from the novel. Using geographical information systems, she charts the travels of the author and his fictional characters to show how and when they overlap. Drawing this direct connection between the two can only be done using the archive, and Alberts contends more work like it can be done by others.

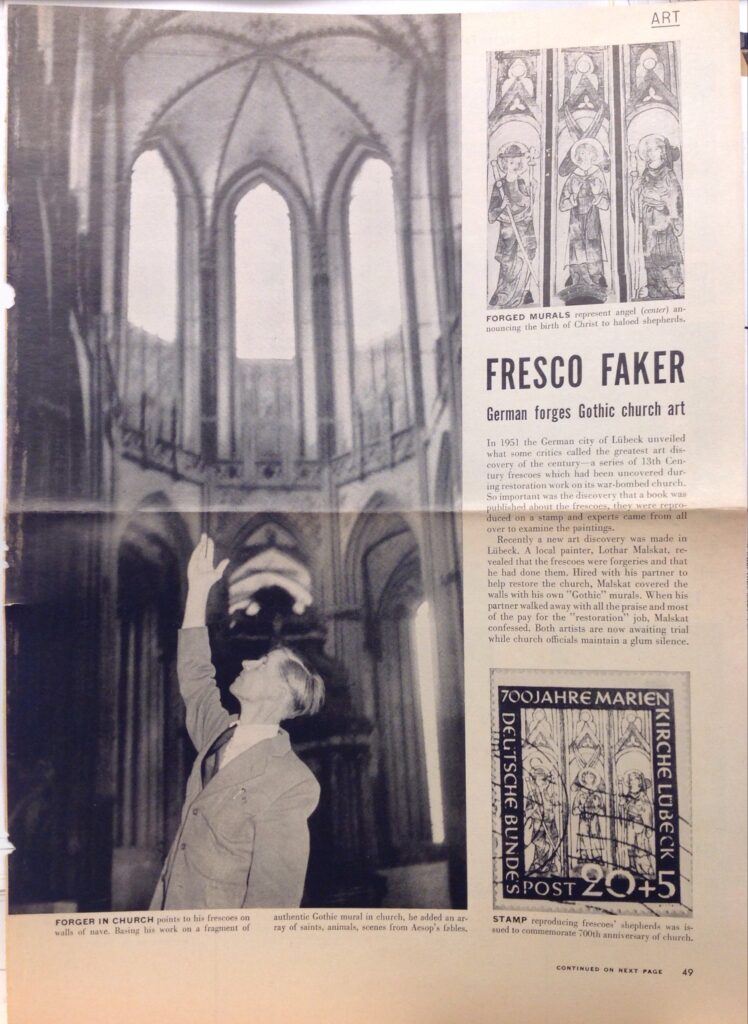

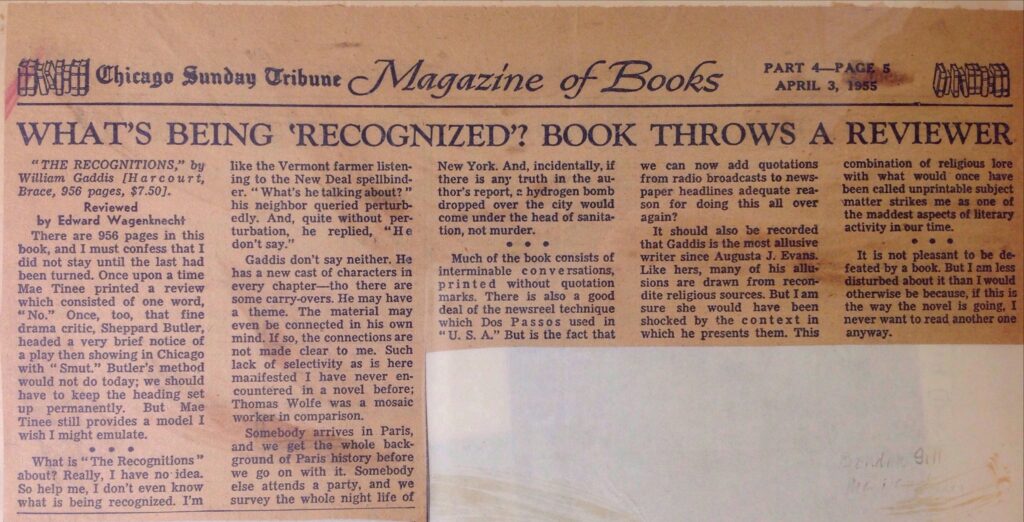

As Alberts notes in “Valuable Dregs,” in addition to key correspondence and notebooks, Gaddis also filed in his Recognitions boxes the reviews, articles, and essays related to the book. Many of the negative reviews when The Recognitions was first published in 1955 were called out by name in a series of particularly scathing issues of Jack Green’s newsletter, called newspaper.

Published in 1962 when a paperback edition of The Recognitions was garnering a second look from readers and critics, these newspaper issues, titled “Fire the Bastards!”, were in effect reviews of the reviewers, and gained a notoriety of their own, eventually published as a book in 1992 with an introduction by invaluable Gaddis critic Steven Moore. But as pointed out in a notation on one copy of newspaper in the archive, “it also had excellent reviews,” and the clippings bear that out.

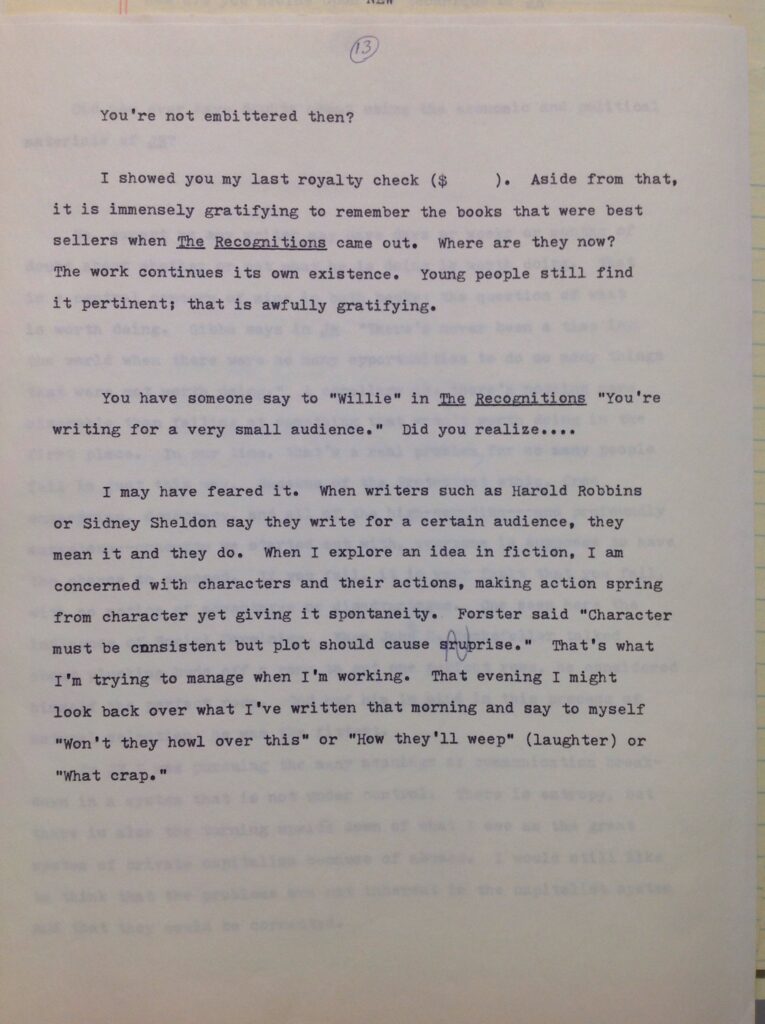

Also included in Paper Empire is a theretofore unpublished interview that postmodern literature critic Tom LeClair conducted with Gaddis in 1981. Gaddis filed his original typed responses to LeClair’s questions, many of which address central themes of not only The Recognitions but J R, his two published novels at the time. He returns to the idea of making order out of disorder as what most drives him as a writer.

The Recognitions may not have gotten the “recognition” it deserved when it landed in 1955, but as Gaddis noted to LeClair in 1981, considering that most of the contemporary bestsellers had by then been all but forgotten, the author was no longer embittered about it. Indeed, through at least six subsequent editions, numerous foreign editions, and critical studies, it certainly has taken its rightful place in the pantheon of 20th-century fiction.