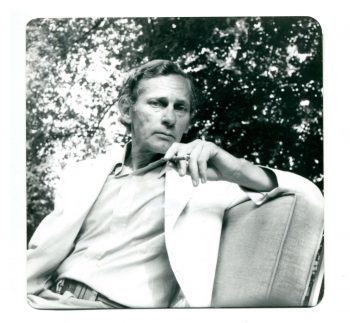

William Gaddis: Where These Lines Lead—Part III

An Interview with David Ting

In this three-part series, Princeton University student David Ting discusses his research on William Gaddis, his experience with the Modern Literature Collection, and his connection with Gaddis as a bricoleur of historic and cultural fragments.

ML: Does it feel freeing to give a body to all these bits and pieces, or is it kind of overwhelming?

DT: Overwhelming.

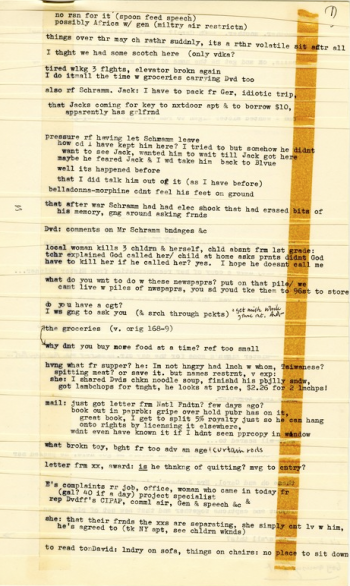

I’m reminded of a word in German that was used to describe Thomas Bernhard: Zeitungsfresser, which means, ‘newspaper devourer.’ You’ll find it in the afterword to The Loser. Gaddis’s were identical. There are hundreds, thousands of newspaper clippings in the collection. He produced subplots from headlines. He hoarded articles, clippings, and advertisements for the player piano. After reading a novel of Bernhard’s he said, “this guy plagiarized my ideas before I had them.”

That’s why he ended up plagiarizing a couple of lines from Bernhard for Agapē Agape. I looked through his copy of Bernhard and saw a number of vertical markings by the lines he appropriated into his own published work. There were so many hints and traces everywhere.

His markings are numerous, but they are simple. The primary varieties are vertical marks, check marks, and underlines. As a quick example, these are abundant in his copy of Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. When I think of a passage that exemplifies Gaddis’s struggle with the concept of being a “difficult” writer, I think of the introduction to that book, the attention Gaddis paid to it as evidenced by those markings. In it, Carnegie talks about his reading, how—after reading Freud, all the contemporary psychoanalysts, all the classics, Aristotle…—this is the book that he’s come up with. (laughs) Carnegie’s saying, “You don’t have to read any of those people. It’s all here in this book and this is all you need.”

So, Gaddis is really perturbed by this, but he also recognizes how much of a selling point this is. He questions: if you can sum up all the knowledge into one text, do you need all of the species of truths that the ancients express in their dialogues? Or do you only need a couple of things to make life easy for you (and get rich by)?

Gaddis exhibits his personal concerns through the passages he’s underlined. You might see certain habits—“Flattering People,” for one—that have been especially underlined. Absences of underlining and annotation are also telling. For example, when Carnegie’s talking about compromises, and making it seem like the other person has won when really you’ve established a foothold in their respect: basically, your ability to make them do something they won’t want to later. Gaddis refuses to compromise on certain points, so you’ll see in this chapter and others: no markings at all. It’s as if he skipped them.

But there’re so many bits and pieces to nibble on, dropped everywhere, dropped in so many different books, and you don’t know whether or not he used everything he annotated. He was notorious for not wanting to discard any scrap of an idea.

While flipping through his copy of War and Peace, I found a mention of a book by Thomas a Kempis—which is what Pierre reads after he’s been introduced to the head of the Freemasons–and according to Tolstoy’s absolute narrator, Pierre picks up this book and feels for the first time his spirit being lifted. Beside this line, Gaddis has drawn a faint pencil mark. Then, in The Recognitions, you find the same name, Thomas a Kempis, contrasted against the character of Wyatt Gwyon, who is also searching for that same epiphanic state and exaltation of freedom.

This process of finding one author pulled from another, linked by annotation, starts to feel like a humongous lattice of pretzels. The references have pretzeled so much it’s hard to tell what came from where. My work is trying to untangle that a little bit, to see how he’s using his corporate background to tinge his arguments against technology in JR or Agape Agape. I’m trying to trace back.

ML: What do you feel your responsibility to those “pretzels” might be? To what extent does your research act as a body or parcel for those complex connections, and to what extent are you yourself putting out fragments?

DT: I think the parceled statement at the end, that eureka moment where you say, “Aha, now I know where all of these lines lead!”… You discover the statement. You invent the parcel. The key is preventing that sentence from being a verdict you can memorize without much engagement…or put into practice without having to open your eyes.

That’s where all the fragmentation comes in. You have to see what it took, how many years it took, how many sheets of carbon paper, yellow legal pads. You see the pretzel first. Then, you get the parcel.

It’s almost vulgar to talk about an epiphany as a parceled object. In order to prevent anything from being completely useless and floating off into a space of its own, you have to allow it to penetrate your life in some way. The aesthetic has to permeate the daily, otherwise it doesn’t have much use for us. That has become a big problem.

For me, my duty, the obligation I feel in showing this pretzel—making it visible—is: I’m foregrounding an unheard timbre of Gaddis’s voice for contemporary America…looking closer at invasion by corporation, mechanization, alienation, and the artist as an oppressed outsider.

I don’t know how many people are going to end up reading my thesis. That’s the problem of publishing anything; you don’t know who it’s going to affect, or how, or if it’s just going to get buried among all the other theses and dissertations. But at least for me, I want the chance to walk in the footsteps of someone I greatly admire, to see if I can come to some of the same conclusions he did. I’m looking for a way to open up a conversation about Gaddis that hasn’t happened before. And I want to increase his readership, even if only by single digits.

ML: What are some of your objectives for the future of this project?

DT: I don’t know at this point if it’s going to be expanded or condensed. I might panel it in conversation with another author concerned with art and technology, maybe Pynchon; these two authors were my heroes when I was in high school. Everything remains to be said. If I could contact Joseph Tabbi, Stephen Moore, or any of the other important scholars who have worked on Gaddis to share something new that I find, that would be great. I like to take things one step at a time, though.

ML: But you know that you definitely want to share it in the future.

DT: I would like to, yes. I don’t want to box up an epiphany and put it on a shelf.

ML: Have you worked in other archives—whether through Princeton or anywhere else—prior to your experience with the MLC? How does this experience differ and compare?

DT: I’ve worked in Princeton’s Special Collections and I think the experience differs based on what material you want to pull out. You can go to any university with certain materials you’re looking for and have a good experience … get what you’re looking for, or maybe not. There, I was mainly concerned with Herman Melville’s copy of Paradise Lost. I was looking at the marginalia, trying to figure out Melville’s intellectual development, because Melville is a writer responding very much to the European tradition.

I think the main thing that irritated me was the mildew…but you get over that. (laughs)

I like the Princeton Special Collections as well as I do here, but for the purposes of my Gaddis research, the Modern Literature Collection is perfect. It has everything. Everything I need.

ML: Do you have a particular sensation of this collection as a writer yourself?

DT: As a writer, I’m enamored with this collection’s pieces of Gaddis, Gass, Nemerov, Merrill, Beckett. I like seeing the big questions they worked with, the many notes they took, or the sparseness of their journals. They’re examples. We don’t necessarily have to follow them, but it gives you an idea for how to tune your own routine and practice, to help you become the writer you need to be.

I’m interested in writing poetry after med school. As Chekhov says, “Medicine is my lawful wife and literature is my mistress.” When I get tired of one, I go to the other.

I guess there are several famous doctors in the history of the lit world. Francois Rabelais. Louis-Ferdinand Celine. (laughs) What a terrible man.

So far I’ve been more interested in reading literature than medical texts. This summer I was hoping to split time between the archives and MCAT prep but that did not happen. The archives swallowed me. Even in my spare time, to unwind from Gaddis’s voice—which I’ve heard hours and hours of every weekday—I go into the stacks and start pulling books. I’m reading John Ashbery, James Merrill—I have the Changing Light at Sandover waiting for me. It just makes me happy to meet a lot of different people. That’s how I’ve always considered novels: as a chance to spend time with somebody, listen to them at your own pace. You get to learn from them. It helps you become a better reader. And it also helps you shape your writing. That has been very important to me.

ML: Do you have any questions for me?

DT: As a writer, having had this conversation, how do you think you might use the archives?

ML: That’s a really good question. I’ve been thinking a lot about that since I started working here. There’s a lot of anonymity in an archive, a lot of people who disappear into the fragments. I think you take for granted how much of this material is unidentifiable until it passes through your hands.

DT: Yes…sometimes it’s hard to look at a small piece, a scrap, and know what’s really important.

ML: I’ve always been interested in ghosts, memory, material that slips into the ether of time. I’ve always been interested in fragments, the idea of making them tangible in some way. Specifically, the kinds of rhythms we assemble, diurnal rhythms, the minutiae of day-to-day life. The way they develop a particular sensation on the page. An accumulation.

DT: Yes, you said earlier that you were interested in how Gaddis’s voice accumulates across the course of a novel.

I’m beginning to see the process of cultivating a writer’s voice informed by the archives. Witnessing the evolution, the conversation between not only a writer’s works, plays, and poems, but also the moments that are not completely formed. The embryonic moments. The richness you glean from them.

(Here, William H. Gass discusses the evolution of critical discourse around William Gaddis’s writing.)

For more William Gaddis materials, visit the William Gaddis Papers or the MLC Digital Archive.