William Gaddis: Where These Lines Lead—Part II

An Interview with David Ting

In this three-part series, Princeton University student David Ting discusses his research on William Gaddis, his experience with the Modern Literature Collection, and his connection with Gaddis as a bricoleur of historic and cultural fragments.

ML: I really like the idea of a novel as a space to meet different kinds of people. You said something interesting about how, through the course of this research, you feel you’ve come full circle. In some ways, it sounds like you view this project as a kind of archive, a collection of the values and ideas you’ve accrued through the course of your education.

What is your particular experience with archives? How do you feel the Modern Literature Collection has served you as a resource for this project?

DT: I’ve been amazed by the quantity of the William Gaddis Papers. I was quite excited and a little bit nervous to rifle through one of my favorite author’s pages. Gaddis saved nearly everything, from what I know, so many scraps and bits of paper. It’s an expression of the quality of the archive when the smallest bits of paper have been neatly arranged among the larger sheets.

From those bits and pieces, to the working drafts, to the manuscripts, with the final published work you see on the shelves, you can assemble a full idea of Gaddis’s process. You can see the perfectionism that plagued Gaddis. In his papers, certain phrases appear over and over again. For example, “pushpin pushkin” is a phrase that appears only once in Agape Agape. It’s this pun about people who hear the name Pushkin and think, “what do you mean, a pushpin?” because apparently the public is so uneducated that they no longer know of this Russian great, Pushkin. This phrase is repeatedly written on different pieces of paper, as if he’s trying to find a place in the novel where this two-word phrase will fit exactly.

There’s also a nexus of content that forms in response to the Austrian author Thomas Bernhard’s novel The Loser. Gaddis makes notes continuously to the effect of, “I’m going to take a couple lines from Bernhard and plagiarize them, put them right into the novel without attribution.” These phrasal pebbles are deposited all over the notes, typed out over and over again.

This repetitive habit formed prior to his writing The Recognitions . Before he decided on the title of his first novel, he drafted other titles, one example of which is “Ducdame.” He penciled these titles in various gothic scripts and then inked them in very carefully, as if they were the title pages of 17th-century manuscripts he’d imagined himself starting. After making headway, Gaddis would stop so he could retype on fresh sheets from the beginning, often only with changes of one or two words.

I think the collection is incredibly well-organized and I’m happy that I’m able to see these pages right next to each other. You get to feel, very tangibly, the evolution of process, of single sentences that contribute to a finely crafted clockwork.

ML: What is the effect of physically being in an archive, of personally viewing these fragments opposed to researching Gaddis online?

DT: You sense the sheer quantity, paging through the repetitions, proofs, scribbles. The scent, also. The age. I think any archival research online, while it gives you the text—which is the cheaper, freer take-away—is absent of that sense of volume, the sense of touch. You find unexpected marks of the author on the pages. Thumbprints in ink.

I think there’s a chill that goes through anybody when they’re rummaging through the papers of somebody they’ve long admired and find an everyday note—for groceries, perhaps—that reminds you that these were people too. They weren’t just papers at one point.

But of course, Gaddis would be happy to simply “be” his novels. He liked living his life out on the page. “Heard and not seen” was his phrase at the acceptance speech for the National Book Awards in ’76.

ML: I’d like to know more about your project itself. From what I understand, its focus has reshaped itself through the course of your research. What is the basic outline of your project? When you’re doing this research, what are you looking for?

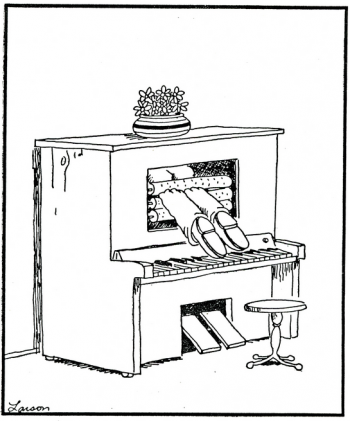

DT: The three biggest reducible terms are art, technology, and science. A practice we used to revere for its creativity is now changing, shifting with the advent of machines who do our work for us. I’m looking for the dialogue between art and the encroachment of technology and science. That comes across most strongly in Agape Agape.

The collection is especially important to me for its entire catalogue of Gaddis’s research on the player piano, which stems from before the publishing of The Recognitions up to the time he died. He was always trying to figure out how an artist grounds himself against a world of machines and electronics. That strain I’m looking at—art, technology, science—is a relevant crisis for anyone working in visual media, sculpture, architecture. I’d originally hoped to write a study about references to alchemy in The Recognitions. Last spring I took a class with Jennifer Rampling and Thomas DaCosta Kaufmann on science and art in the Renaissance. We discussed alchemical writings, how paintings relied on scientific ideology, theories of light.

With that foundation fresh in mind, I’d hoped to take a crack at The Recognitions and see what literary scholars without backgrounds in the history of science were missing. I’ve speculated about the amount of alchemical information in The Recognitions after peeking at Stephen Moore’s A Reader’s Guide to William Gaddis’s The Recognitions, which is an annotated bibliography of Gaddis sources. I saw in the first 100-200 pages that alchemy kept popping up. I thought, maybe I’ll use this class knowledge to cover an area that hasn’t really been addressed.

Delving deeper into the critical literature, I learned that some literary scholars had already looked at the relationship between Gaddis and alchemy. As I went through his swamp of drafts and notes, I found less alchemical content than I’d hoped. Slowly, the option diminished of making a 75-100-page thesis on this topic. As I continued researching, I departed from The Recognitions to look at JR. There, I became interested in the technology of the corporation, which has its roots in the assembly line.

ML: And you were returning to your own roots as well, going back to the first Gaddis book you discovered.

DT: It’s a nice way to return, but 4 years ago I would’ve never recognized all the things that JR was doing. I hope I’ve matured a lot as a reader. Now, my project might encompass all of the novels, speaking to Gaddis’s massive intellectual grasp on how different systems of law, science, religion, and society cohere, coexist, and work against each other. What I’m finding, more and more, is that I can’t only talk about art and technology. I have to also figure how these languages bleed into each other. So, the project is just getting bigger and bigger.

At this point, I think after I go home and allow my brain to cool off a bit, I’ll be able to whittle down the massive chunk I’ve bitten off. But right now I do really want to focus on the replacement of the artist by technology. That’s quite frightening, and it’s even more relevant now than it was at the time of Gaddis’s death.

ML: Do you feel that in the course of your reading, filtering through fragments, you’ve come across anything that surprised you?

DT: I didn’t know Gaddis was such a big reader of Plato. I don’t remember so many of those references in JR because the last time I read it was several years ago, but I read The Recognitions more recently to trace allusions. His copy of the Dialogues is quite marked up. So, while I’d previously thought of JR as a novel unmoored from tradition, built around big, stylistic leaps, it’s actually in conversation with the classics. I would like to return to the corporation and its ethics, as this is of course an animal of a species different from anything Plato and his contemporaries could’ve imagined.

That opens up new avenues for Gaddis researchers who have otherwise been framing Gaddis’s work alongside DeLillo, Gass, and Pynchon. How do we position Gaddis in the notorious “Western Canon”? I don’t think scholars have given him enough attention as a responder to tradition.

For me, one of the collection’s biggest advantages is the access it gives me to Gaddis’s personal library, all the books that he annotated. I think that’s also an area that previous researchers hadn’t really looked into. Seeing all the slight resonances in Plato or Socrates, and cracking them apart, you get a sense of where Gaddis might’ve found some of his ideas. Coming here and digging into the archive has yielded a lot.

For more William Gaddis materials, see the William Gaddis Papers or the MLC Digital Archive.