William Gaddis: Where These Lines Lead – Part I

An Interview with David Ting

In this three-part series, Princeton University student David Ting discusses his research on William Gaddis, his experience with the Modern Literature Collection, and his connection with Gaddis as a bricoleur of historic and cultural fragments.

ML: When and how did you first become acquainted with the work of Gaddis?

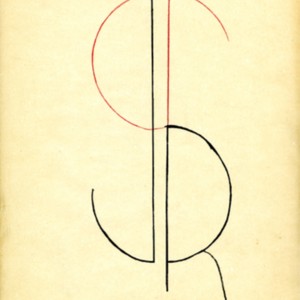

DT: The summer before my senior year of high school, I started reading a lot on my own. A friend had recommended me Dracula, and I found the text online via the Gutenberg Project. I realized there were a host of texts available there for free. These were the big classics I’d heard about—Joyce, Dickens, Balzac, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy. After Dracula I thought, I’m going to come back to this site, there’s a lot of cool stuff here. I read more and more, and I posted these books to GoodReads. Eventually, GoodReads recommended William Gaddis’s novel JR, which is about a young boy who is introduced to the Wall Street system and decides to build a corporation of his own making.

Months passed before I actually read anything by Gaddis. I physically came across his work for the first time in Princeton’s campus bookstore, Labyrinth, after I’d recently been admitted. A copy of JR was sitting on the shelf (from Dalkey Archive Press, which has also published a beautiful edition of Gass’s novel The Tunnel). I bought JR and immediately began to read it.

It took me a month to finish, but it was such a welcome break from all the other fiction I’d experienced, stylistically. Its subject also felt unique, as there has been no American narrative work that tackles the corporation so well as JR. I decided to read his other novels–A Frolic of His Own, Carpenters’ Gothic, and his final novel Agape Agape, which hit me as the most succinct and accessible version of his voice. In Agape Agape, he directly addresses the reader about his concerns with art and the absence of the artist in a mechanizing world, a world that permits the unskilled to make work that would otherwise have been reserved for the prodigious or virtuosic in another era. He has a line in Agape Agape about “every four year old with a computer,” speaking to the idea that with software programs, you can now sketch up a whole bunch without needing any expertise.

That voice spoke to me because I wanted to write a creative thesis for my undergrad at the time, against those forces, and Gaddis’s was a voice that rang close to my ear and straight to my heart.

After reading Agape Agape, you begin to hear his voice in blips. Those blips are otherwise unnoticeable in a work like JR where there are so many different voices it’s easy to get lost in the tunnel. But after hearing what his voice is like or at least meeting the alter ago and recognizing how that fictional self speaks, you begin to hear his voice elsewhere. Seeing the circuit selves through which Gaddis speaks, I felt the desire to return to my roots as a reader, to go full circle by writing a thesis on Gaddis. His was the voice that wrapped me up in literature so much in the first place.

ML: I really like what you said about hearing Gaddis’s voice in blips. That’s a good lead-in to another question I had about his specific voice and the ways his tone is often read. Some of Gaddis’s enthusiasts and literary compatriots have spoken of him as an intellectual or difficult writer. Do you share this sensation of his difficulty? Do you feel that’s a useful distinction to make about his work? And how do you see “difficulty” as a running theme or progression throughout his work?

DT: Whenever he interviewed, Gaddis liked to tell the press that he didn’t intend for his books to be difficult, that it’s really what people make of them. Keeping that in mind, there were plenty of moments in JR where I had no clue what was going on. Notoriously, the difficulty is due to the unattributed dialogue; if you take a quick flip through the pages, you’ll see that every line of dialogue by a new character is broken up by a (—). A quick glance reveals dozens of (—)s rifling, raining out of the page, and that’s really scary. It’s really scary to wander into a novel and have no idea who’s talking, who’s cursing—and then the TV cuts in.

The TV actually is one of the coolest stylistic innovations of JR. After an unbroken stream, it’s musical when suddenly the TV snaps on and it’s Smokey the Bear in an ad for the National Park Rangers. Moments like those manage to assuage the difficulty. It gives you enough humor to keep rolling along.

But I don’t think people should be so intimidated by the unattributed dialogue. As Gaddis himself said, he wants his readers to take everything in at spoken pace. It’s quite slow. There’s no need to rush with it. He asks us to appreciate the musical flow of the language, which I think is enough. Not everything that he’s writing about has to hit you. You don’t have to grasp everything. You just have to get the feeling.

That’s why I think the transmission of his rage in Agape Agape is so potent. It’s a direct access. It’s the feeling that counts, not the density.

ML: Do you feel like there are specific moments where Gaddis’s voice speaks really strongly, or do you think that it sneaks up on you through a slow accumulation?

DT: To me, it seemed that the end of JR when the boy is talking on the telephone about his idea for a new company (even though his last idea for a company, the JR Family of Corporations, had just failed) was a moment where Gaddis was tapping at the reader, asking, “hey, are you listening?” It could seem like Gaddis was being cranky, adopting that persona. However, he’s actually trying to express something essential about the American spirit: the idea that even after it’s failed, it will get back up on its feet and try the same things over again, sometimes without having improved in any way ethically. (Laughs)

It is a slow accumulation. You have to pay attention really closely if you want to catch things. He demands total rigor from the reader. To my mind he’s saying, “if you’re going to pick up my book, you’d better listen.”

ML: On the subject of adopting different personae: I’ve heard that you’re going on to pursue studies in another realm (the medical field) after your BA. What role do you think this project might play in your future? Do you feel a kinship with Gaddis as a fellow writer who worked within different fields (documentary filmmaking, PR) throughout his life? Do you feel like having a cross-disciplinary background has informed your research?

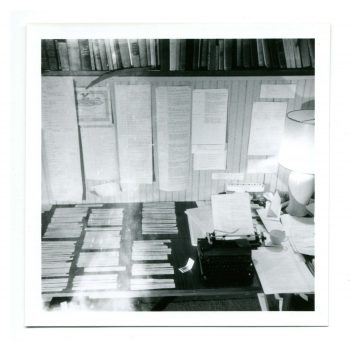

DT: Being a History of Science major, I don’t think Gaddis was ever skilled or knowledgeable enough about a scientific profession that he could have pursued one as a career, though in the years between publishing The Recognitions and JR he worked for IBM, and other industry giants. He was mainly channeling the scientific information he gleaned from others, then putting a slight spin on it in his scripts, ghostwritten speeches, and education proposals. He often bends scraps of scientific information towards an aesthetic purpose. You’ll find Thoreau dropped in along with a line about television education.

For me, his dabblings in science are not interesting as the work of a scientist but rather as somebody who comes from the humanities, who manages to take in scientific information and mash it up with the humanities allegorically. I’ll be going to med school after college and I don’t see much in Gaddis that would interest any doctor seeking medical information. I’m just interested in Gaddis because I like art.

ML: I’m curious about your plans for this project. Is this something that fits into the broader scheme of your career, or is it something you’re pursuing primarily because it’s personally rewarding to you in this moment?

DT: It’s personally rewarding to me because it brings me full circle from where I was at the beginning of college. It’s a metric of how I’ve grown. The benefit of the humanities is not always obvious for someone going into a career in science, but I think they develop your soul.

Through his novels, Gaddis gives you a fuller picture of the human race. He builds this picture in bits, through observations about how a corporation is run, notes about the way people’s voices sound when they’re ticked off—little tips that help you adjust your behavior when you’re around other people. You’re meeting a lot of people whenever you open a Gaddis novel.

A lot of these points have recently been expressed by Joseph Tabbi in his biography of Gaddis, Nobody Grew But The Business. Tabbi stresses that paying attention is the most important thing when you open a Gaddis novel. Paying attention is a good lesson for those in the medical profession as well. I think there are ways to cross-train your brain between soft science, hard science, humanities, engineering. There are ways the disciplines can learn from each other.

For more William Gaddis materials, see the Wiliam Gaddis Papers or the MLC Digital Archive.