The Medieval Mind of Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892-1973), the English writer known to many for his celebrated fantasy novels The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings trilogy, spent much of his life fascinated with medieval history. Several books in the Rare Book Collections display the influence of this era and its myths upon his work.

From a young age, Tolkien possessed an avid interest in languages and mythology. After fighting on the front lines in World War I, he held an academic career as a professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University. In addition to giving lectures and developing literary criticism, Tolkien wrote his fiction alongside the members of the Inklings (an informal literary group including members such as C.S. Lewis, Owen Barfield, and Charles Williams).

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings were published between 1937 and 1955. Decades after their release, these stories still find great resonance in the world today—in large part, it can be argued, thanks to the author’s interest in medieval culture and mythic story structures.

Myth and Medieval Influence

While most familiar with Tolkien’s work can see his love for the medieval world in the construction and themes of The Lord of the Rings, this focus preoccupied his academic, linguistic, and artistic projects as well.

The medieval era (from Latin medium aevum, meaning “middle age”) is known as the time between the end of the Western Roman Empire and the Renaissance: approximately the mid-fifth century AD to the end of the fifteenth century. In Western Europe, this period was filled with folklore and epics including Beowulf and Arthurian legends such as the Holy Grail. Tolkien was most interested in Norse and Finnish myths and Germanic languages, especially Old English. His academic output surrounding Beowulf includes a prose translation which was published posthumously. Artistically, he appreciated the creations of visionary William Morris, who printed many medieval classics as a leader in the nineteenth-century Arts and Crafts movement (to find more about Morris’ Kelmscott Press, see the Triple Crown Collection).

For all his serious academic concern with myth and story, Tolkien wrote about these things with joviality and humor. It was important to him that he craft a world that felt real and complete (what he called participating in “sub-creation”), but he wasn’t afraid of inverting literary traditions, either. For example, instead of following the customary quest storyline in which the hero goes in search of an object or person, Frodo in The Lord of the Rings already has the One Ring and is seeking to destroy it.

Tolkien in Special Collections

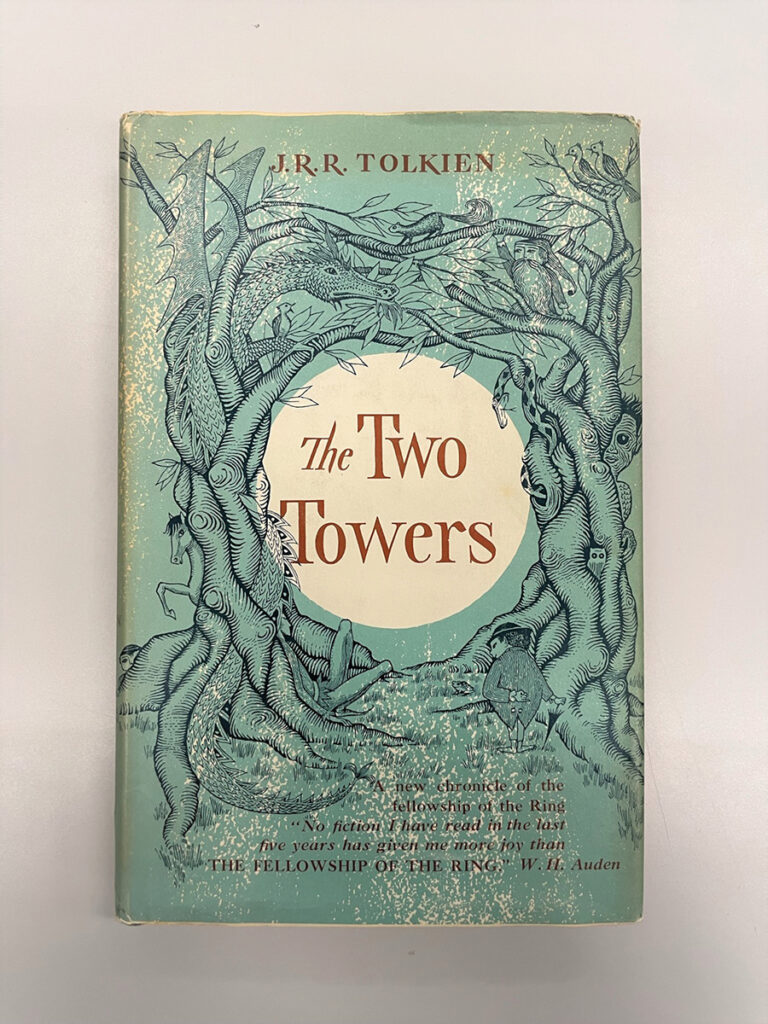

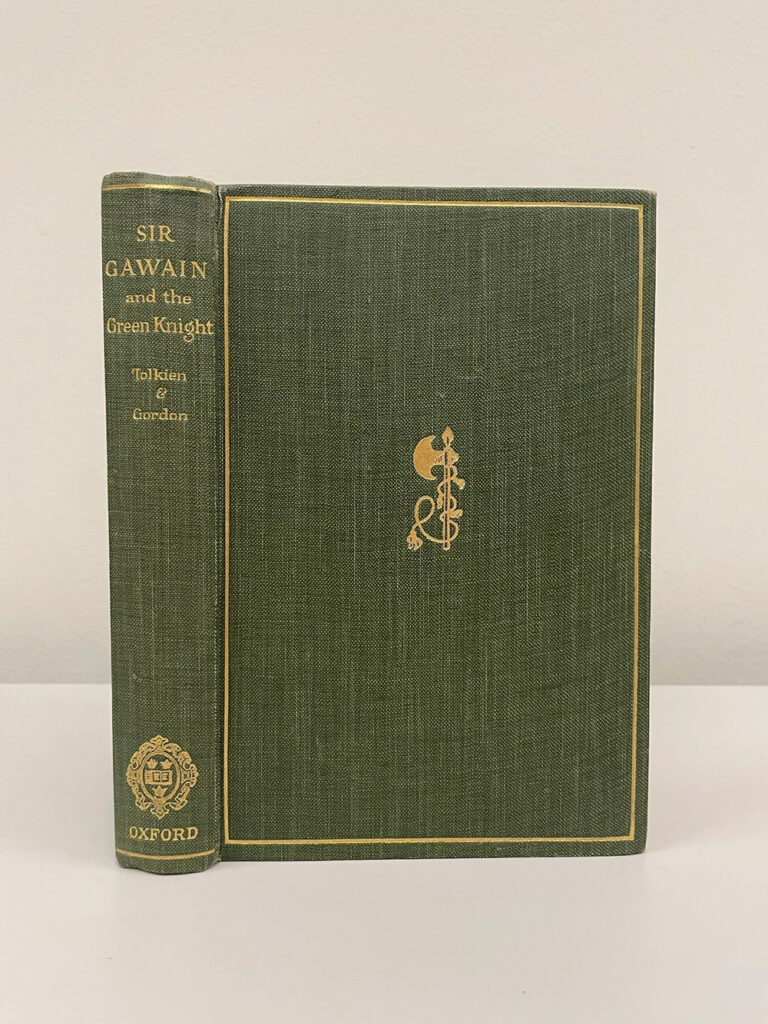

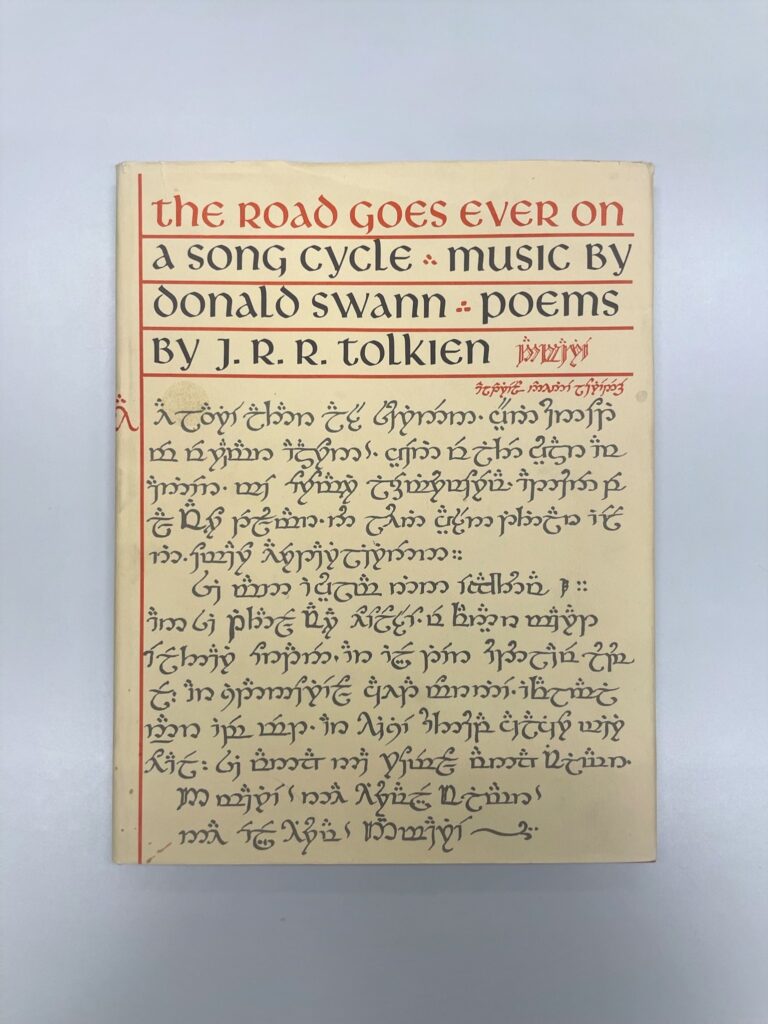

Special Collections’ Tolkien selections include his edited version of the medieval text Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a first American edition copy of The Two Towers, and books featuring reproductions of his illustrations and musical settings of Tolkien’s poems by British composer Donald Swann. Other works in Rare Books include texts inspired by Tolkien’s writing and historical renditions of the legends that inspired him.

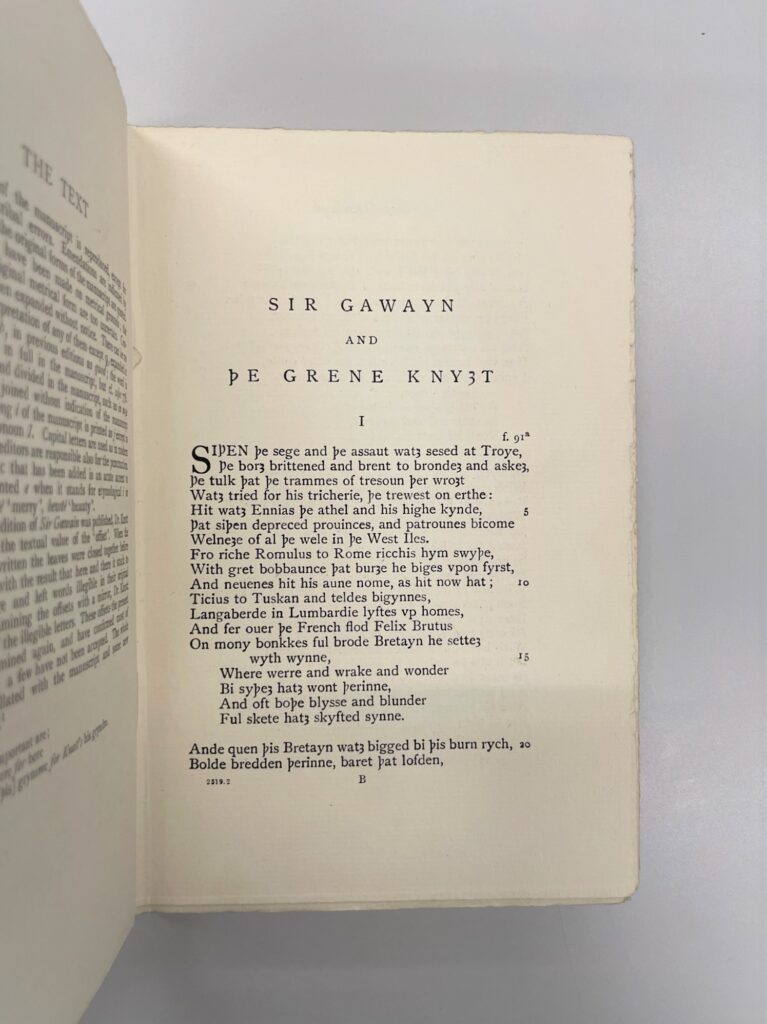

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a significant Arthurian romance from the late fourteenth century. In the story, Sir Gawain (a Knight of the Round Table) takes up the challenge to win the axe of the Green Knight. His quest is circular, leading Gawain to return a changed man—not unlike Bilbo’s journey to go “there and back again” in The Hobbit. Tolkien co-edited this copy of the Middle English text with E.V. Gordon and would later write a translation that was published after his death.

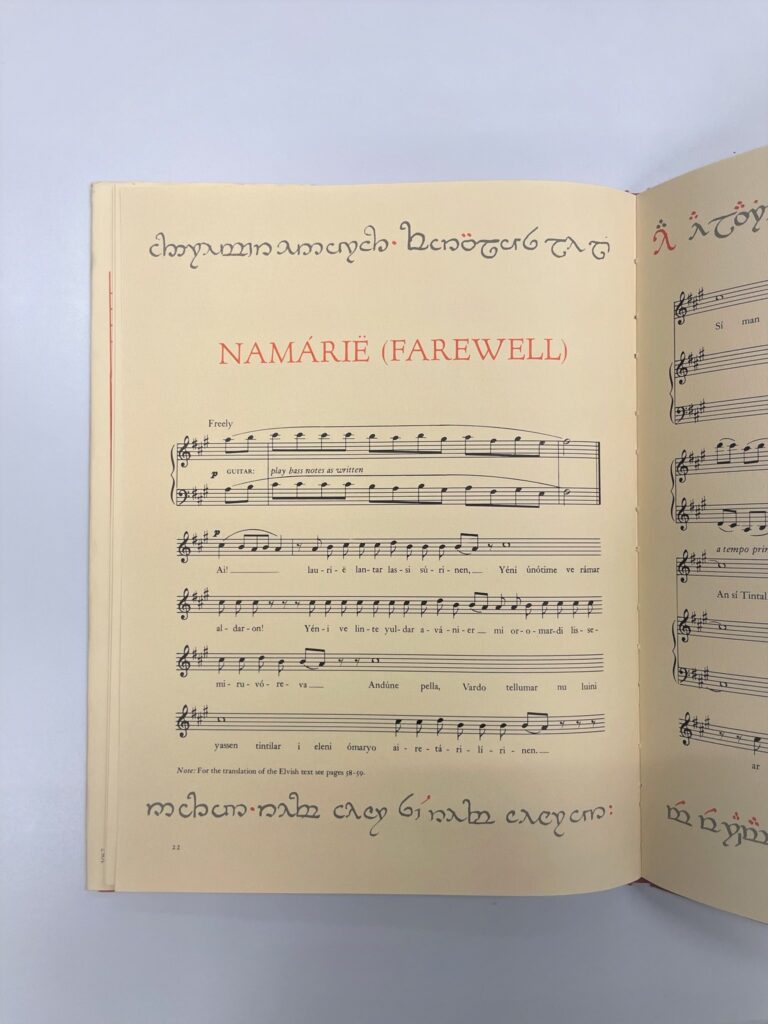

In the 1960s, English composer Donald Swann approached Tolkien with music he had set to several of Tolkien’s poems. The then-retired professor approved five of the songs but balked at Swann’s version of “Namárië,” Galadriel’s farewell in The Lord of the Rings. Tolkien hummed the tune as he had always imagined it, drawing from the tradition of Gregorian chant (a Roman Catholic form of sacred song developed during the ninth and tenth centuries), and Swann transcribed it.

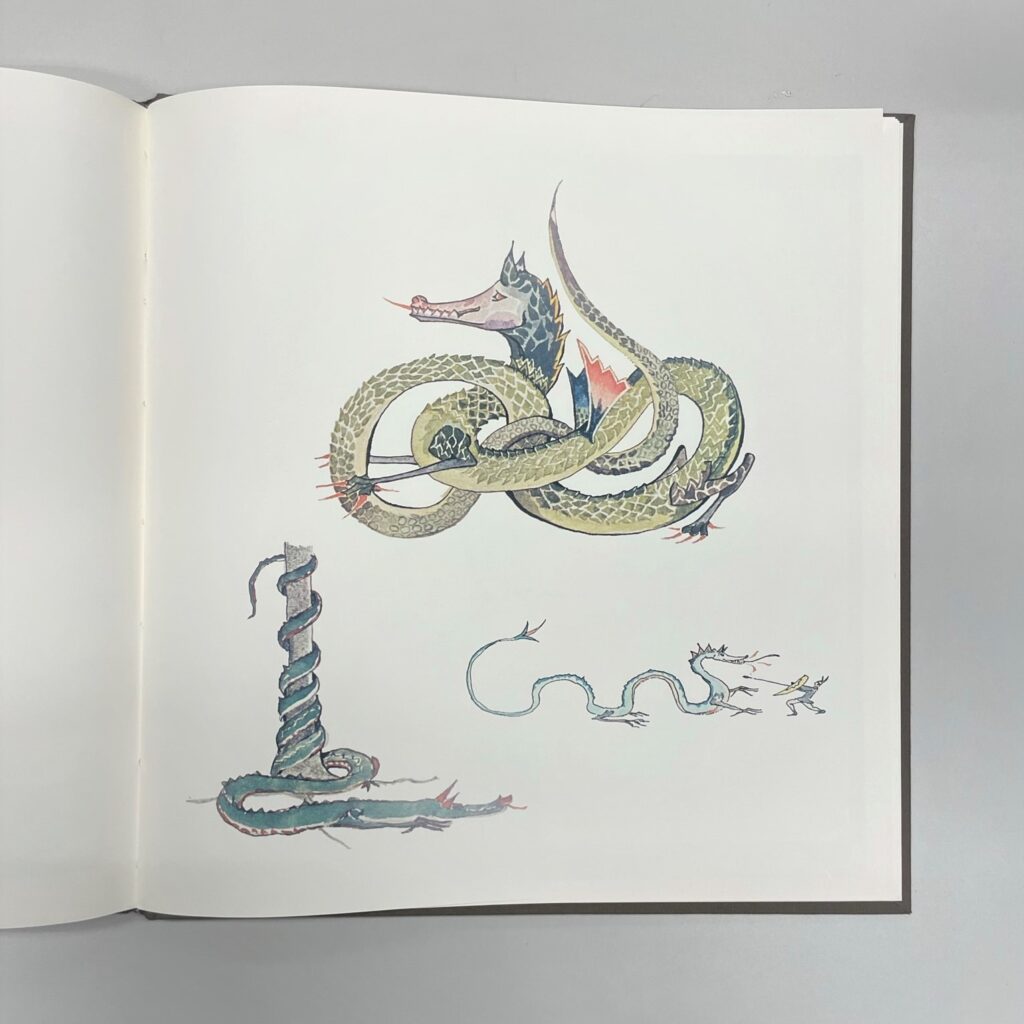

While Tolkien was not an artist by trade, he did produce many illustrations in the process of writing his fiction. These drawings range from penciled landscapes of Rivendell to colorful heraldry for the island kingdom of Númenor, whose history is chronicled in Tolkien’s The Silmarillion, Unfinished Tales, and the appendices of The Lord of the Rings. The above dragon illustrations are inspired by Nordic knotwork and decorative elements in medieval illuminated manuscripts.

To take a closer look at these and related materials, set up an appointment at Special Collections by emailing spec@wumail.wustl.edu or calling (314) 935-5495.

Further Reading

Lee, Stuart D. and Elizabeth Solopova. The Keys of Middle-Earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Tolkien J. R. R. On Fairy-stories. London: Harper Collins, 2014.

Bernadette Lamb is an MFA in Illustration and Visual Culture candidate at the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts.