The Life and Mystery of Poet Elizabeth Jennings

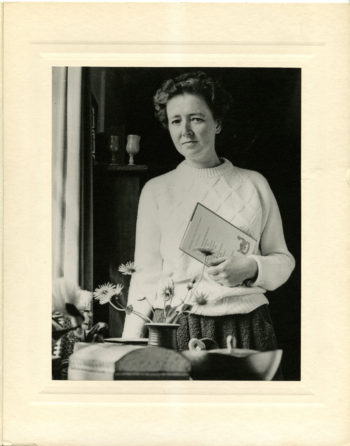

Poet Elizabeth Jennings (1926–2001) led an extraordinary life: the only woman to join the Movement (an English group of poets dedicated to an anti-romantic aesthetic); publisher of twenty-six books of poetry in her lifetime; colloquially known in her later life as the bag-lady of poetry due to her immense poverty; and a dedicated Roman Catholic. Much of her work touched on the periods of her life when she was interned at a psychiatric hospital, though she maintained that she was not a writer of autobiographical poetry.

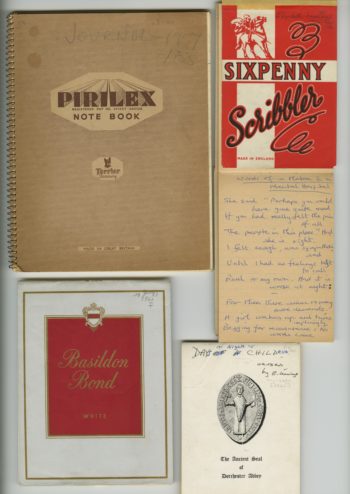

If it were not for the large amount of correspondence and personal notebooks Jennings left behind, it would be difficult to piece all of these aspects of her life together. As a writer, she exalted formalism, striving to maintain a sense of tradition through regular meter and order. In the context of her tumultuous interior life, and her desire to bring this depth of pain into her work, she both respected the Confessional label and shied away from it (as it had become a pejorative term).

Her desire to be in communion with others and her need for isolation was a constant topic of discussion in her letters, as well as a theme in her poetry. She maintained lifelong friendships over correspondence. Rugena Stanley, a Czech refugee, whom Jennings met when at the Warneford hospital, helped her recover from and survive later bouts with mental illness. Other friends, like Dame Veronica Wedgwood, were a source of literary support, and even went as far as typing and editing Jennings’ poems.

While Jennings’ work stands on its own as an expression of a fragmented psyche struggling to live simply, when read in context with her biographical accounts, her poetry can be understood as an almost obsessive quest to fully understand herself. Dana Greene, the author of the first Jennings biography, The Inward War (which shares its title with Jennings’ unpublished autobiography), spoke with the Modern Literature Collection about Jennings’ work. “She almost never revised but would rather write another poem, perhaps on the same theme. This does not allow for a comparison of revised poems, but it gives evidence of the themes which preoccupied her —love, nature, faith, death, friendship, the seasons, childhood—over her lifetime.”

Greene researched the Elizabeth Jennings Papers in the Modern Literature Collection (MLC) for her biography of Jennings because the only original, handwritten copies of her unpublished autobiography are here. Greene: “There were two other iterations of this work, but they were “cleaned up.” The MLC version was more direct in its language, and its title – “The Inward War” – was revelatory. The later iterations were titled “Autobiography” and “As I Am.” Although none of these autobiographies was ever published, Jennings used the title “The Inward War” for her subsequent and unpublished biography of her favorite poet, Gerard Manley Hopkins.”

At the end of her life, Jennings struggled with poverty and ill-health. As the Elizabeth Jennings Project states: “The downtrodden appearance of her later years (cardigan, skirt, ankle socks, plastic carrier bags) became something of an anecdote, culminating in her refusal to deviate from this costume for a dinner at Rules Restaurant to celebrate her CBE Honour or her appearance at Buckingham Palace.” Her legacy has perhaps suffered from her decline in popularity in her later years, but her poetry remains potent for those wanting to read about estrangement, loss, the ordinary, and the sacred.

For those interested in hearing the work of Elizabeth Jennings, poet and professor Mary Jo Bang read “In Praise of Creation”; “World I Have Not Made”; “Ballad of War”; “Years Ago”; “Dream, A Ballad” at the Modern Literature Collection’s 50th Anniversary. The reading was held in John M. Olin Library’s Ginkgo Room on November 20, 2014.