Shakespeare’s Fun with a Pun on Bunghole

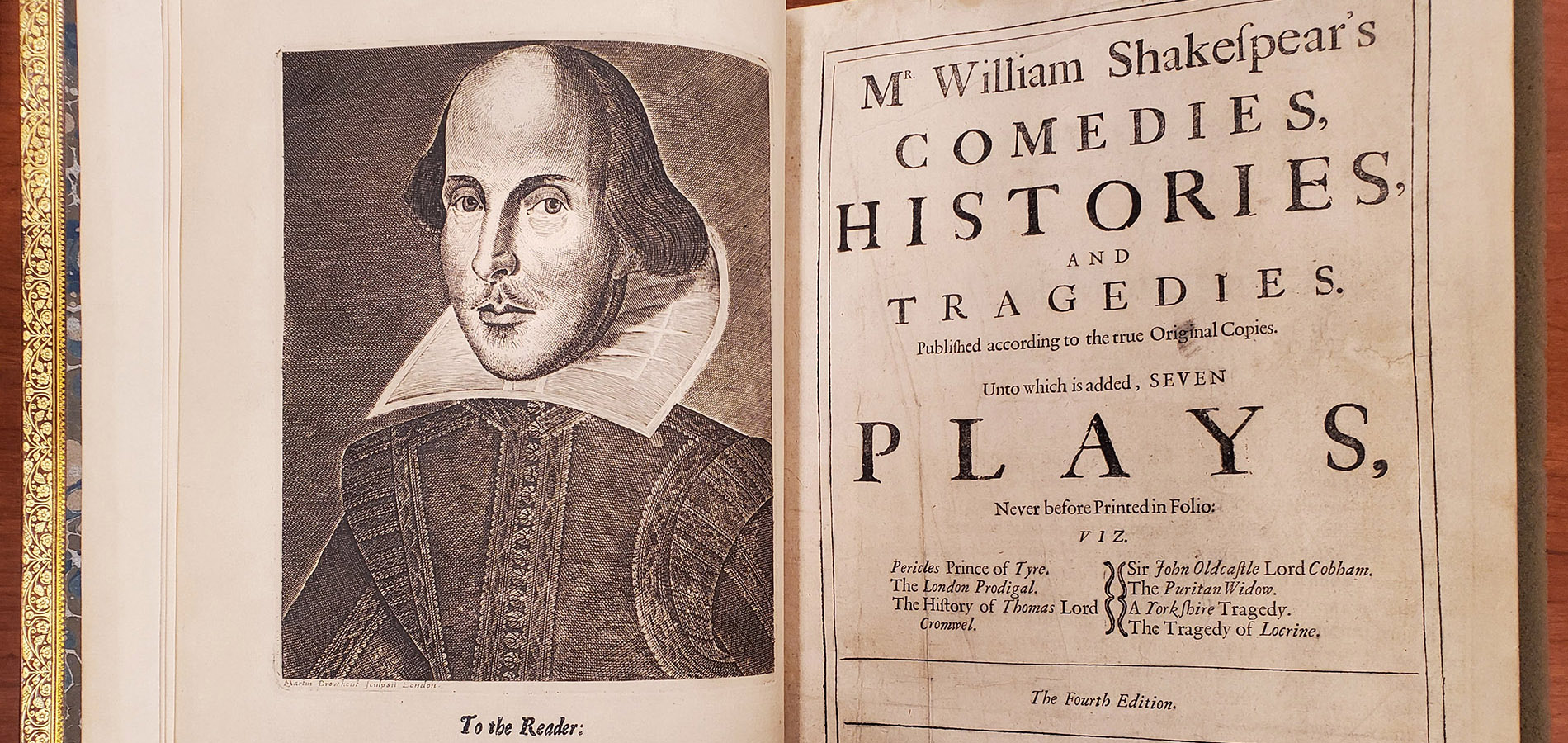

A new exhibition in John M. Olin Library celebrates the 400-year anniversary of the first folio—the first time William Shakespeare’s collected works were printed. The Play’s the Thing: Shakespeare in Special Collections brings together numerous objects and artifacts from Special Collections that highlight the playwright’s best-known works. Numismatist and WashU alumnus Eric P. Newman traced the earliest use of the word “Bung,” which he first encountered in the form of the Bungtown copper—the counterfeit English halfpence—to the fifteenth century and noted its appearance in Hamlet. Items from Newman’s papers in Special Collections are on display in the exhibition.

Genuine and Counterfeit Halfpence

The English halfpenny was the most frequently encountered copper coin in colonial America, analogous to today’s Lincoln cent. Unlike silver and gold coins, the melt value of the halfpenny was less than its face value, and these pieces thus circulated with limited legal tender status. Still, the need for small change led to widespread acceptance of these debased coins.

At the same time, because counterfeiters could produce imitation pieces at less than face value, many of the circulating halfpence were fake. In 1753, 40 percent of the circulating copper in England was found to be counterfeit. English anti-counterfeiting efforts led to many of these coins being exported to colonial America, where even more imitation pieces were being produced. While American coining technology lagged behind Europe, at least one operation, Machin’s Mills in New York, produced counterfeit halfpence in the 1780s.

Genuine examples of the George III (1738-1820) halfpence were produced between 1770 and 1807. The obverse depicts a laureate bust of George III facing right, while the reverse exhibits a seated figure, representing Britannia, with a spear and shield to her side. Britannia sits on a globe, no doubt intended to convey the worldwide influence of the British Empire. The Machin’s Mills pieces are clearly cruder in manufacturing style; the dyes are less textured, the rims are uneven, and the overall fabric is somewhat reminiscent of folk art.

Eric Newman and the Bungtown Coppers

Over time, counterfeit English halfpence circulating in America became known as “Bungtown” coppers. Eric P. Newman (1911-2017), numismatist and graduate of Washington University Law School (’35), endeavored to understand the origin and usage of the word “bungtown,” a study that led in an unexpected direction. Newman traced the usage as far back as 1787, when the Newport (RI) Mercury used the word in reference to imitation halfpence. Newman put forth North Swansea, MA, as the most likely site of the word’s origin. This city was called “Bungtown” in earlier times and had a history of counterfeiting activity, both coins and paper money.

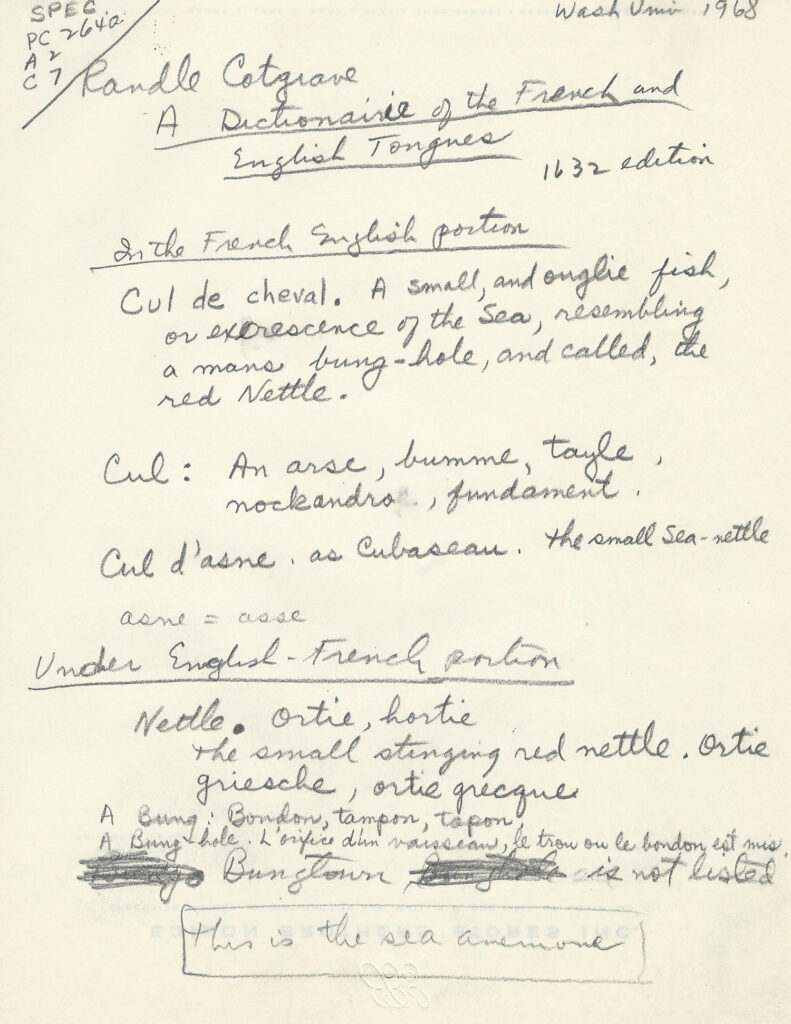

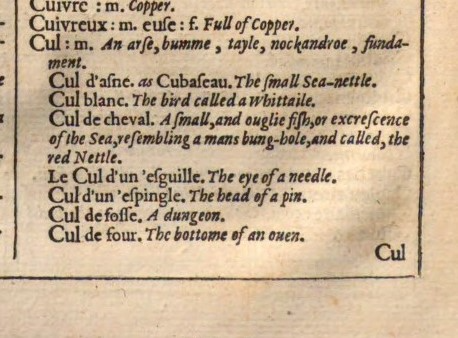

Digging further, Newman traced the term “bung” as far back as 1632, when it was included in Randle Cotgrave’s A dictionarie of the French and English tongves. Here, the comparison with the red nettle fish leaves no doubt that the word “bunghole,” in the time of Shakespeare, constituted a reference to the anus.

Shakespeare’s Use of Bung

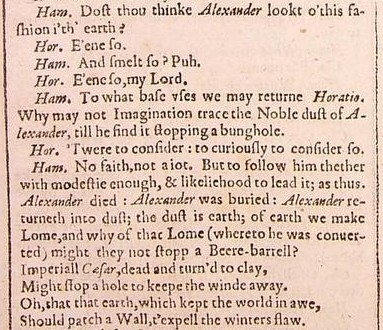

Newman discovered such usage in Hamlet (Act V, Scene I) that relies on the double meaning of “bunghole” as a barrel stopper. In this graveyard scene, Hamlet and Horatio graphically contemplate the disintegration of corpses into dust:

Hamlet: Dost thou think Alexander looked o’ this fashion i’ the earth?

Horatio: E’en so.

Hamlet: And smelt so? pah!

Horatio: E’en so, my lord.

Hamlet: To what base uses we may return, Horatio! Why may not imagination trace the noble dust of Alexander, till he find it stopping a bung-hole?

Horatio: ‘Twere to consider too curiously, to consider so.

Hamlet: No, faith, not a jot; but to follow him thither with modesty enough, and likelihood to lead it: as thus: Alexander died, Alexander was buried, Alexander returneth into dust; the dust is earth; of earth we make loam; and why of that loam, whereto he was converted, might they not stop a beer-barrel?

Imperious Caesar, dead and turn’d to clay,

Might stop a hole to keep the wind away:

O, that that earth, which kept the world in awe,

Should patch a wall t’expel the winter flaw!

Newman, the son of a proctologist, summarized in his essay, “American Circulation of English and Bungtown Halfpence” (American Numismatic Society, 1976):

“It … becomes apparent that Alexander has been converted to dust, to loam, to food, and into feces. The feces stops up the lower bowel and prevents the expulsion of flatus or gas from the anus. Then follows the simile of expelling the winter’s flaw (flaw being a sudden gust of wind) by it’s being held back by a patch in a wall.”

Shakespeare’s Bawdy and the Shakespeare Bulletin

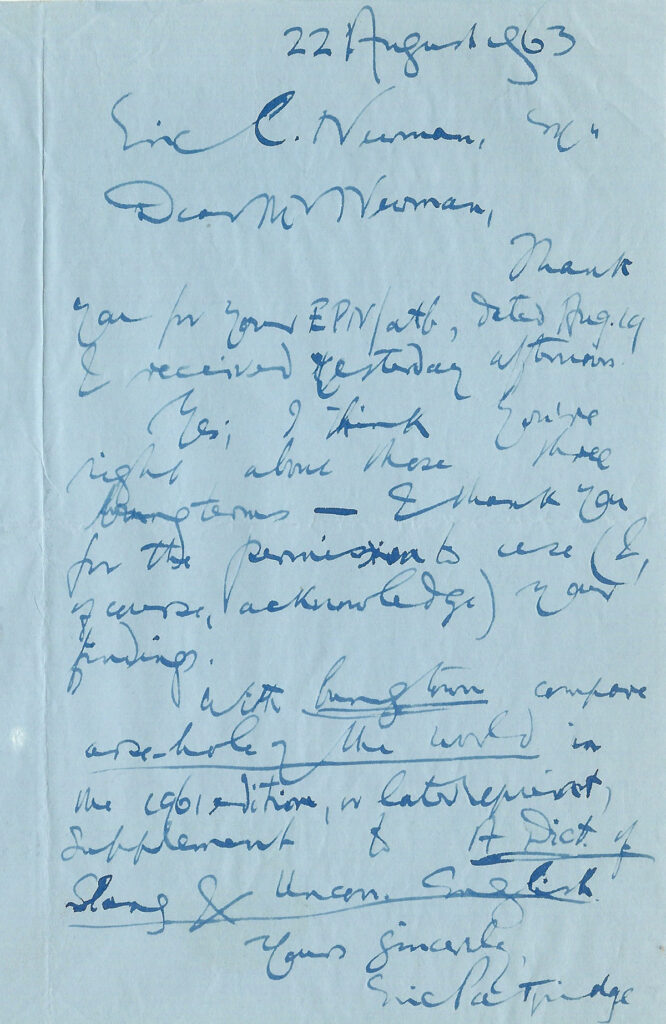

Newman shared his findings with Eric Partridge, English lexicographer and author of Shakespeare’s Bawdy. Partridge wrote to Newman on August 22, 1963, “I think you’re right about those three bung terms & thank you for the permission to use (&, of course, acknowledge) your findings.” Partridge noted the usage in the 1968 edition of Shakespeare’s Bawdy. The Shakespeare Bulletin, in 1991, published Newman’s “Shakespeare’s Fun with a Pun on Bunghole.”