Roots/Routes: A Thousand-Year-Old Story of Migration

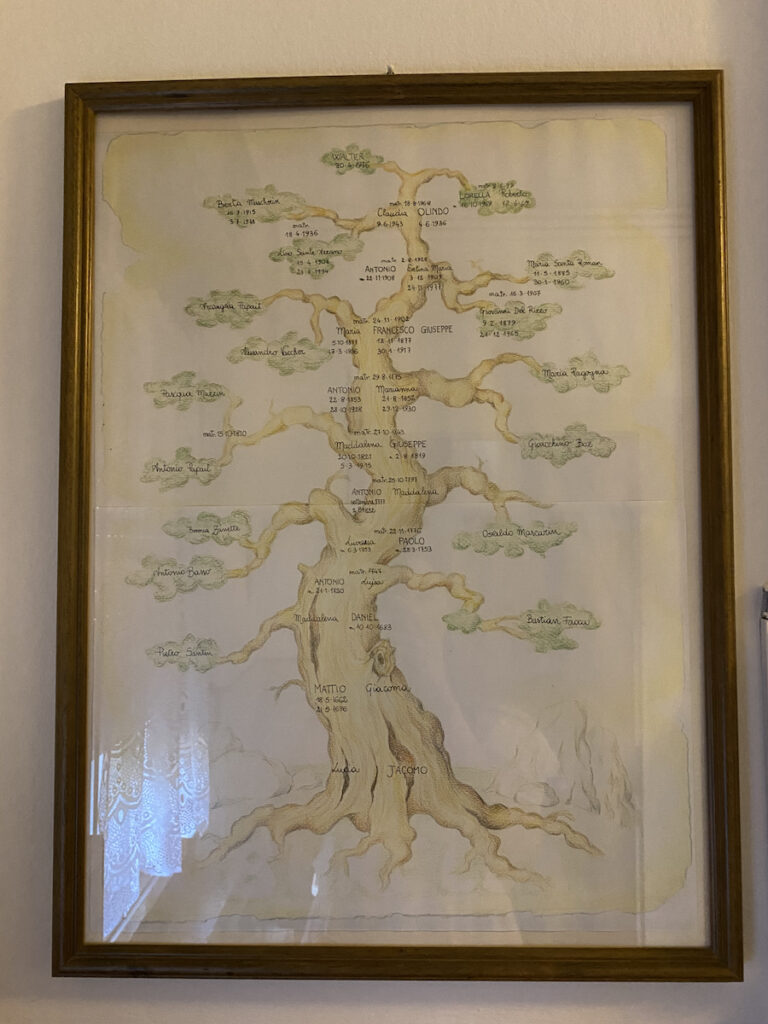

Last December, I sat down at my childhood kitchen table, looking at old, black and white photographs with my nonna. One after another, she showed me images of lively dinner tables from decades ago, filled with wide smiles and laughter. Arms wrapped around each other—sisters and brothers, aunts and uncles, cousins, and friends. My nonni (grandparents) immigrated to Canada in the 1950s and 1960s from Northeastern Italy and while my mother is well-connected to her cousins overseas, I’ve always felt this sense of unfamiliarity with that side of my family.

The connection between two sides of a family separated by an ocean is like a fraying rope. Separated by time and distance, then language and culture, the rope gets thinner as each generation goes by. Now, with video calls and instant messaging, we can hold on to that rope more easily than ever before. But how do you hold on to someone you don’t know?

This summer, I returned to Italy for the first time since I was twelve years old. It felt like a re-introduction. My cousins—ones who I remember playing with through broken words and hand gestures because we didn’t know the other’s language—were all grown up. We discussed our lives and interests, our jobs and studies, and our history. I learned that many more of my relatives came to Canada before eventually returning to Italy, and I wondered what life would have been like if they had stayed.

I was also joined by my mother and nonna; it was beautiful to see them reconnect with their generation. She brought me to the church where she and my nonno were married. We met one of her friends from school whom she used to walk home with every day, both of them now with families of their own. I asked her what it was like to come to Toronto, she was so young when she moved away, and I can’t imagine what that journey felt like. I’ll never know that feeling, but I traced that journey’s footsteps.

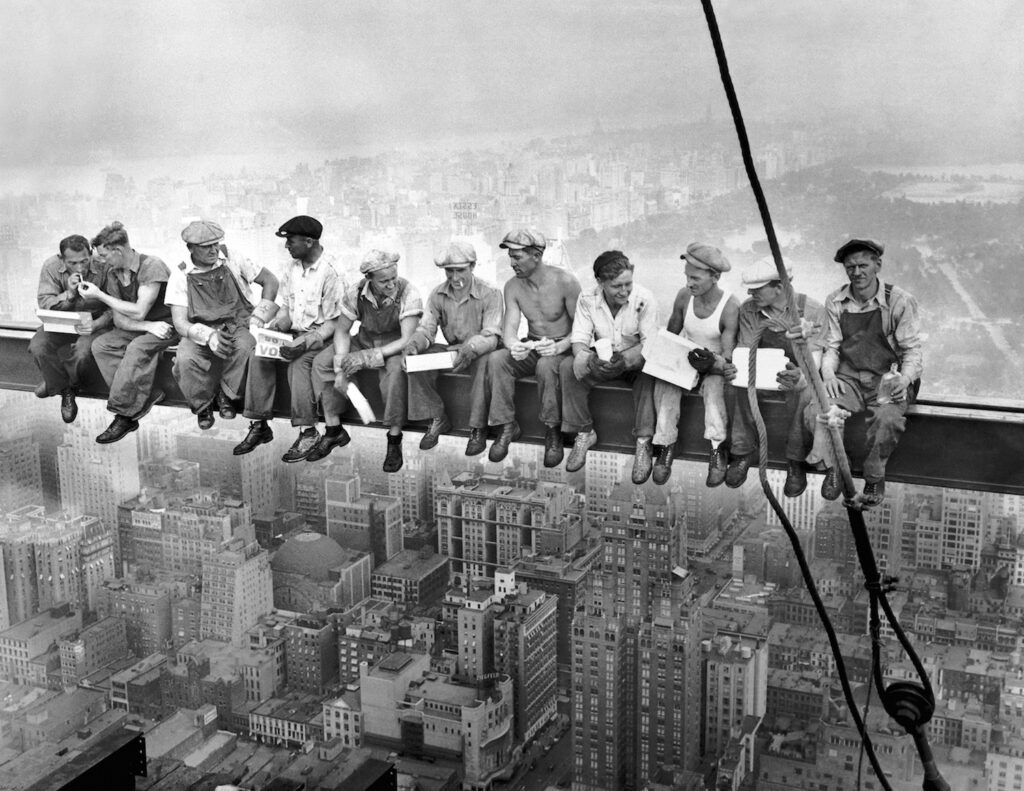

From my nonni’s hometown of Azzano Decimo, I boarded a train to Genoa, where my nonno emigrated. Genoa is a beautiful Northwestern city on the coast of the Ligurian Sea, with colorful apartments lining the nearby hills. Inside a twelfth-century building, Genoa is also home to the Italian Museum of Emigration. Their exhibits simulated sitting on the steel skeleton of a high-rise building using an array of mirrors, after the iconic photo Lunch atop a Skyscraper. They detailed stories of emigrants from all points of history, as well as many promises that were told to them that were not always honored or true. One particularly impactful exhibit was The Labyrinth, a literal maze where you interacted with digital customs agents of various countries who were often hostile and spoke in a language you didn’t understand let alone speak. You would be denied entry if you made the wrong move. This only scratched the surface of the obstacles and hostilities that migrants often face.

From Genoa, I traveled again by train to Naples, a much larger city farther in southern Italy. My nonna emigrated from Naples, and to this day vows never to step foot on a boat again. Coming from the rural northeast, the hustle and bustle of such a large city must have been intimidating.

Her story of coming to Naples to begin a new life was juxtaposed with the storied life of the city itself. Naples has a rich history spanning millennia, with modern-day tightly-packed apartments overtop Roman architecture and a maze of tunnels that snake underneath the old town. It is also home to the National Archaeological Museum. Among scores of magnificent mosaics and marble statues, the museum contains some of the oldest artifacts from Paleolithic (Stone Age) populations from the area. This brought me to my other purpose for traveling to Italy and the final phase of my trip: Sicily.

Sicily is considered by many scholars to be the earliest island in the Mediterranean region to ever be occupied by humans, but when and how this feat was achieved remains unknown. Sicily is less than two miles from mainland Italy, which may seem like a small distance but would have been extremely difficult for early human migrants to cross. I traveled to Sicily to join the Early Occupation of Sicily (EOS) Project, an archaeological research project led by Dr. Ilaria Patania, a former post-doctoral researcher in the Department of Anthropology at WashU. The EOS team searches for land and underwater paleolithic sites that contain fossils and archaeological remains to shed light on the timing and modes of the earliest human migrations over the Mediterranean. To encourage public understanding and interest in the deep past and to make sure their research benefits the local community, EOS incorporates citizen science projects into their research agenda, and that is what brought me there this summer.

EOS collaborates with local divers, museums, schools, libraries, and other cultural institutions to preserve and contextualize their work. The team is based on the eastern side of the island in Augusta (Ilaria’s hometown), where there exist many open-air and submerged archaeological sites nearby that have not yet been studied. Ilaria invited me to join her team to collaborate with the Museo Civico di Storia Naturale di Comiso (MSNC), where a new hall of Sicilian archaeology is set to open. I drove sixty miles from Augusta to Comiso to see the museum for myself. The MSNC is the only natural history museum with a research laboratory on the southeastern side of the island and their collections are incredible, which is in no small part due to the passion of the museum’s director. He gave me a tour of the museum, eyes dazzling at each exhibit and specimen. The museum proudly displays collections that represent incredible natural history from around the world but especially highlight the extraordinary biodiversity found in Sicily. From the iconic dwarf elephant of the Middle Pleistocene to a wall of colorful Mediterranean sea creatures, the museum tells a beautiful story of the evolution of life in the area and how it has transformed over time.

Together with the museum’s director, we are creating a series of educational posters that will be displayed alongside the new archaeological exhibit. These posters will also be freely available online and distributed to schools and libraries. By creating these stand-alone pieces that introduce what it means to be an archaeologist and discuss how archaeological evidence gives us insights into how human tools and technology have changed over time, our goal is to create resources that have long-lasting benefits that extend beyond EOS to highlight the importance of archaeology to the modern-day.

These posters are the first of many outreach projects that I will work on with EOS, and Ilaria and I agreed that to understand this work and be able to capture its significance, I needed to see the sites themselves. So, we geared up and hopped on a boat to one of the cave sites on the coast of the island. First found in the 1870s by a German naturalist, this cave was lost to memory until the EOS team rediscovered it last summer. Our boat anchored away from the cave’s edge to avoid hitting rocks nearby we swam inside, climbing up sharp rocks onto the rocky and muddy cave floor. We turned on our headlamps and saw animal fossils littered across the floor. These fossils show that the cave was periodically occupied by animals and humans from the middle Pleistocene to the Crusades. Ilaria described the signs of occupation, how distinct layers of dirt indicated different periods, and how she could identify the period she was looking for. We even found a small obsidian blade, distinctly glossy and sharp among the dirt and bones. She took me to the different areas of the cave where they will excavate, and into the back chambers of the cave where even more areas are sealed off from compounded dirt. In many areas, the cave floor was wet from where the tide had swept in. The rising sea swept away material that she remembered from last year but could not excavate; now gone forever. The evidence that remains of how the earliest humans lived in the area is already few and far between, and every year that goes by risks losing the only information we have.

On the last day of my journey, I took one last swim in the sea and breathed in the salty air. I had traveled from the cool mountains of northeastern Italy to the hot, arid landscapes of eastern Sicily. I reconnected with loved ones, explored the regions of my cultural heritage, and felt that rope becoming stronger again. I met passionate and brilliant people who inspire connection to our natural world and human history. The posters we made will be donated to schools and libraries this winter to share the importance of archaeology with young students. This experience and all that was created from it would have been impossible if not for the Newman Exploration Travel Fund’s generosity. It created another rope, one that extends across the sea to an island in the middle of the Mediterranean where this story first began, thousands of years ago.