Refugee Access to Higher Education in Western Europe

The juxtaposition of beauty and struggle was the central theme of my Newman Exploration Travel Fund excursion. Over three weeks, I traveled to four countries as a personal pilgrimage and research exploration to investigate refugee access to higher education. Upon visiting Paris, Brussels, Berlin, and London, I embraced the history, architecture, and culture of each city, interspersing my days with site visits to universities and community-based organizations, gathering information on how these European countries are attempting to tackle the crisis of refugee brain waste.

I arrived in Paris around 8:00 am on Saturday, May 27, full of the adrenaline one experiences when embarking on a new adventure. With three full days to explore the city before beginning my intense meeting schedule, I set my sights on the thirteenth-century gothic church, La Sainte-Chappelle, followed by a long walk along the Seine stopping to browse the quintessential riverside bookstands. I explored the Jardin de Tuileries until I finally succumbed to jet lag and returned to my quaint studio apartment in the bustling 2nd Arrondissement. The following two days were spent meandering through historic cathedrals such as the Eglise Saint-Eustache and the Eglise Saint-Suplice, a tour of the Louvre, the National Archives, and the Musee du Luxembourg while interspersing these visits with long walks and fresh pastries. As the workweek loomed, I prepared for my site visits and a week of French class in Le Marais.

Part I: Paris

While Paris is a dream tourist destination, the city of love is frequently a nightmare for displaced persons due to rising costs, language barriers, access to employment, and scarcity of housing. Recent 2023 data “indicates that 613,272 persons with refugee status and 64,034 asylum seekers” were registered across France. Among the top five resettlement countries for displaced persons, France has been forced to develop programming that facilitates integration into French society, workforce, and education. My motivation for visiting Paris was to gain first-hand knowledge of Reseau MEnS, a network of fifty-four institutions assisting exiled students in transitioning into French university programs. At the Ecole de Ponts ParisTech, I was able to spend the day as a student where I participated in French class and community integration programming.

Over a canteen lunch, students shared their stories of exile and their hope for a safer and more prosperous future in France. They detailed the need to improve French proficiency for academic and professional success and that a French diploma would supersede their home country diplomas while providing more visibility in the job market. They also highlighted that beyond the tangible benefits, they were gaining cultural knowledge and a sense of community. The program administrators, Cedric and Firmin, graciously provided me with detailed information related to their intake, curriculum, and guidance processes. Additionally, they highlighted the great need; in 2022, eleven Reseau MEnS programs received over 1000 applications for only approximately 275 spots. I also met with officials from the Sorbonne, Sciences Po, and Reseau MeNS leadership; these visits provided me with a comprehensive understanding of university programs in Paris working to integrate displaced persons into academic and professional programming.

Part II: Brussels

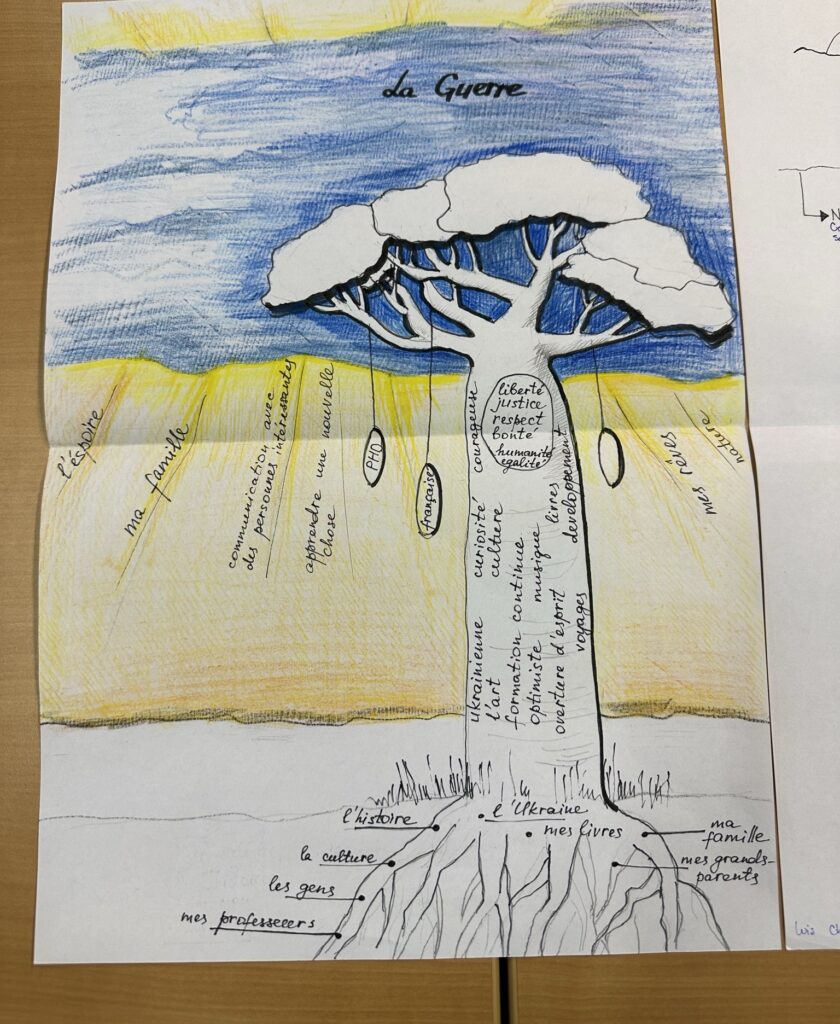

After nine days in Paris, I embarked on the next leg of my journey in a crowded Eurostar train through the French countryside to Brussels, Belgium. Upon arrival, I quickly reacquainted myself with a manual transmission and driving in Europe. My destination was the literal newest town in Belgium, Louvain-la-Neuve, established in 1972, after the historic University of Leuven split between French and Dutch speakers. Louvain-la-Nueve became the site of the new French-speaking Universite catholique de Louvain (UCL). There, I would spend several days meeting with officials and observing classes for the UCL “Access2University” program designed to prepare refugee students to enter Belgian universities. While similar to Reseau MeNS programs in France, Access2University at UCL provides a more robust support system for their refugee students through a network of local community-based organizations, university-sponsored psychological support, access to legal guidance, and integration into UCL student life through peer mentoring. Students engage in academic French courses that combine language study with guided reflective practice. During one class observation, students created “trees of life” to depict their past, present, and future combined with the current obstacles preventing the realization of their dreams.

Several of the students in the class were from Ukraine and Syria. It was striking to see the clear depiction of “war clouds” covering the skies of their future. The instructor conducted the lesson in intermediate French eliciting descriptive vocabulary, yet asking students pointed questions such as, “How does this make you feel?”; “What do you do when you have these feelings?”; “What do you need to overcome these obstacles?”; and “What is worrying you most today?”. Two Ukrainian students described a bombing that had occurred the previous evening in their hometown and that guilt is the prevailing feeling over fear. How can they possibly feel safe, happy, and hopeful while their loved ones are living in such danger with uncertain futures? I sat through the remainder of the day humbled that these students were willing to allow me as a total stranger to observe their classes as well as their vulnerability. It is not easy to leave behind your home, abandon the life you had planned, learn a new language, and be a stranger; yet, given this long list of obstacles, these students were determined to create a new future through the opportunity provided by Access2University. Ultimately, my takeaway from UCL is that the added burdens and mental load that refugee students carry indicate the need for higher education institutions to provide access to specific supports appropriate for displaced persons’ needs beyond academic coursework.

Part III: Berlin

On a Wednesday evening in early June, I boarded a Brussels Airlines flight to Berlin where I had arranged to meet with people from the American institution, Bard College, and the open higher education organization, Kiron. In comparison to the idyllic fairytale locations of Paris and Belgium, Berlin is harsher and more serious; yet, no less full of rich history and, most importantly for my research, asylum seekers.

In 2019, Bard College received funding from the Open Society Foundation for the Open Learning Initiative Project to support higher education opportunities for refugee students. The Open Learning Initiative (OLIve) Project is a full academic year and prepares students to apply for BA programs while supporting students’ language, writing, study skills, and disciplinary knowledge. Bard Berlin is in the Pankow-Niederschonhausen neighborhood, a former politically significant area in East Germany or the German Democratic Republic (GDR); the college resides in former embassy buildings and is architecturally reminiscent of the Soviet era. I had arranged two important meetings for my Bard College visit. The first was with Jeffrey Champlin, the Academic Director for the OLIve Project and humanities faculty member. During this meeting, we discussed programmatic details including admissions processes, finances, academic assessment, language proficiency courses, mental health support, and socialization for refugee students at Bard Berlin. The purpose was to add to my growing knowledge of best practices in higher education bridge programs for refugee students. The second meeting was with a new and influential OLIve Project student at Bard Berlin, Aisha Khurram, who was formerly the Afghan Youth Representative to the UN and an avid activist for women’s rights in Afghanistan. I can’t put into words the significance of my meeting with Aisha. She is a remarkable young woman with a harrowing story of resilience and survival. Aisha was in the middle of her undergraduate study in law at Kabul University when the fragile Afghan government was toppled by the Taliban in 2021, which, as a UN-recognized Afghan female leader, immediately put her life in danger. Through her brother’s assistance and a perilous journey, Aisha eventually made it to Germany. There, she applied for asylum and attempted to put the pieces of her life back together and build a future in international law and human rights work. Our conversation was long and varied, but the predominant point was this simple question Aisha asked me, “If Afghan girls and women are willing to die to learn, what are you willing to do to help them?” Meeting Aisha ignited my already burning ambition to find a way to support the academic dreams of Afghan women now living in the US.

Following my Berlin site visits, I spent a weekend visiting historical sites before flying to my final destination, London. On Friday evening, I walked to the Brandenburg Gate and the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe, a somber and striking dedication. After spending time reading the museum’s first-hand accounts from the Holocaust and sitting in quiet reflection, I eventually made my way to the historically relevant, yet rather kitsch destination of Check-Point Charlie. Walking around Berlin on a summer Friday evening, the city was full of Berliners strolling the streets, sitting by the river, enjoying the warm weather, and basking in the prolonged daylight. Berlin is a unique city; evidence of the impact of WWII remains visible, as does the striking difference in architecture between East and West Berlin. Plus, the city is awash in graffiti, yet it’s clean and orderly and feels inordinately safe.

Part IV: London

I wrapped up this three-week whirlwind tour with my shortest stint in London visiting the University of East London, another Open Learning Initiative (OLIve) Project from the Open Society Foundation. This site was a late addition; the purpose was to visit a program supporting refugees in an English-speaking country.

The University of East London (UEL) is a career-focused city university in the diverse community of East London, which makes it an ideal institution to offer a pre-university refugee support program for students to acquire language skills coupled with discipline-specific courses and career guidance. While visiting UEL, I was able to spend time meeting with the Program Director, Yesim Deveci, attend the current student cohort’s program completion luncheon, and meet with a student focus group. What I learned at UEL echoed much of what I garnered in Paris, Belgium, and Berlin. However, the difference between UEL and my other site visits is the current strong political opposition to illegal immigration in the UK, which includes asylum seekers who arrive in the UK illegally. The path for these individuals to achieve official refugee status is unclear and asylees have limited rights. Importantly, they are not eligible for student financial aid and they are not allowed to work, thereby their futures in the UK are relatively uncertain. Programs like OLIve provide the opportunity for asylum-seeking students to find a pathway into university; however, the options for undocumented students to enter a degree program following OLIve are few. Despite my previous meetings with students who had experienced extreme hardship, the students and the staff at UEL seemed more desperate and anxious regarding the realistic options for asylum-seeking students to achieve academic and professional goals while living in the UK.

Ultimately, I am incredibly grateful to each person who spent time meeting with me during my NEXT excursion. Witnessing programs in progress and meeting professionals dedicated to refugee student success was invaluable. This method of information gathering allowed me to analyze program strengths, weaknesses, gaps, and unexpected hurdles to develop a working model for universities in the United States to support refugee students’ matriculation. As a result, English Language Programs in the School of Continuing and Professional Studies recently received a grant for $491,000 from the Missouri Office of Refugee Administration to begin an intensive language and professional certificate program for St. Louis-area refugees. Thank you to the Newman Exploration Travel Fund for providing impetus for this impactful project.