Reference Volumes on Native American Tribes

As we come to the end of Native American Heritage Month, we want to highlight some of the extensive volumes of 19th and early 20th- century reference books we have in the Edison Department of Special Collections. Although these reference materials are all written from an Anglo-American perspective, their beautiful illustrations and photographs provide a unique, but curated, look into Native American life.

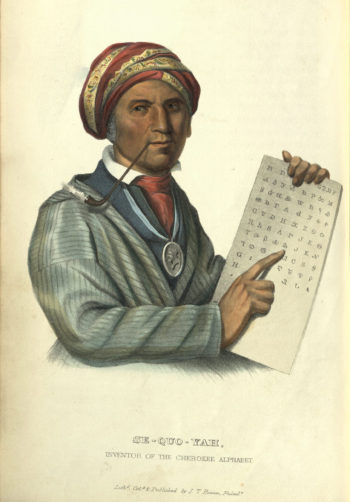

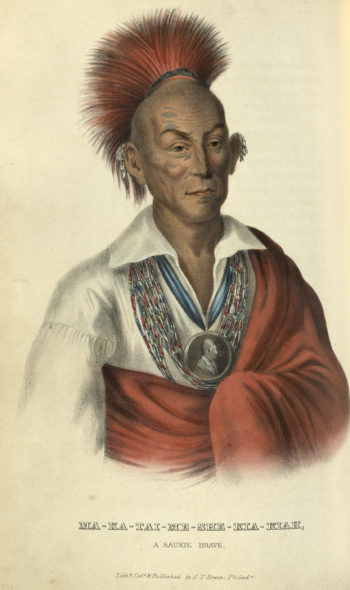

McKenney’s Indian Tribes of North America

Thomas L. McKenney’s three-volume History of the Indian Tribes of North America: With Biographical Sketches and Anecdotes of the Principle Chiefs is the smallest of the three sets of reference books we will be highlighting in this post, but it is also perhaps the most beautiful in terms of its illustrations.

Thomas McKenney was the US Superintendent of Indian Trade in Georgetown and the first director of the Office of Indian Affairs. While he was working for the federal government in these roles, he commissioned painter Charles Bird King to paint the portraits of more than one hundred Native American delegates as they visited the capitol between 1821 and 1842.

The three volumes of History of the Indian Tribes of North America, originally published around 1848, contain lithographs of King’s portraits alongside detailed descriptions and histories of each of the Native Americans featured. The original portraits were unfortunately later lost in a fire at the Smithsonian in 1865.

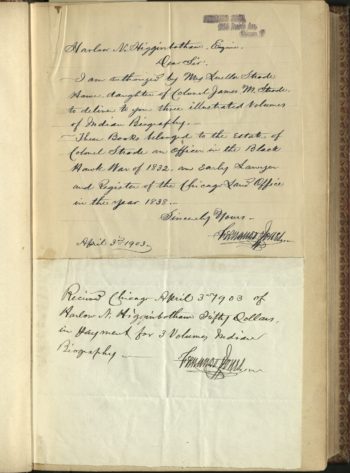

Washington University Libraries’ edition of this set, published in 1854, contains a hand-written note in the front saying that the volumes come from the library of Colonel Strode, an officer in the Black Hawk War of 1832. Black Hawk himself is featured in the volume (pictured above), although the author of his bio says that the reader will be “disappointed at the discovery that, although a respectable person, he was by no means a hero” (213). The descriptions of the Native Americans in this volume strongly reflect the prejudices of its time, and are unfortunately often derogatory and demeaning.

Schoolcraft and Indian Tribes of the United States

Henry Rowe Schoolcraft was an American geologist whose expeditions brought him all over the United States before he finally settled in Michigan in 1822. There he married Jane Johnston, granddaughter of a Ojibwe chief, and had two children with her. His extensive interactions with Native American people led him to begin an ethnological research project on various native tribes, and in 1846 he was commissioned by Congress to create a comprehensive reference work titled Archives of Aboriginal Knowledge : Containing all the Original Paper Laid Before Congress Respecting the History, Antiquities, Language, Ethnology, Pictography, Rites, Superstitions, and Mythology, of the Indian Tribes of the United States.

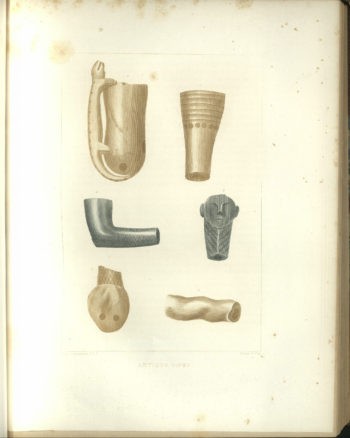

The large six-volume set was published between 1851 and 1857. It contains illustrations borrowed from other texts, including many of the lithographs from McKenney’s work, as well as illustrations of its own, such as the drawing of the pipes below and the sketch of Itasca Lake by Captain S. Eastman above. The latter is based on a sketch made by Schoolcraft himself on one of his journeys.

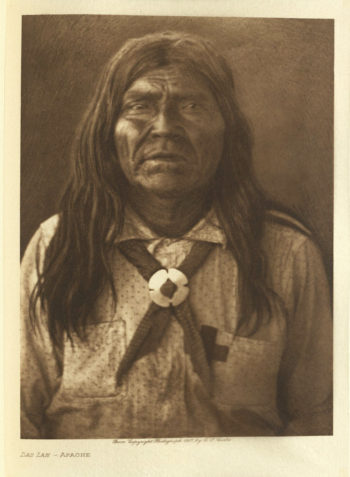

Photographs from The North American Indian

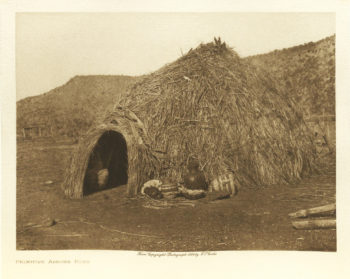

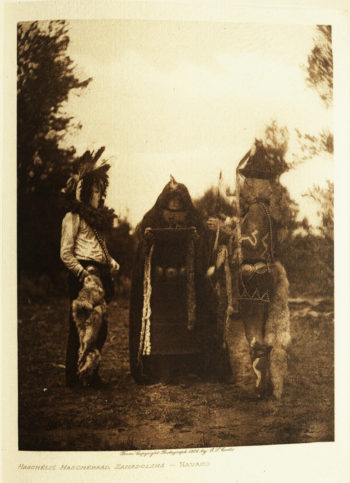

With sixteen massive volumes, Edward Curtis’ The North American Indian: Being a Series of Volumes Picturing and Describing the Indians of the United States is certainly the most massive of our reference books on the Native American tribes. Published between 1907 and 1930, each volume is devoted to between two and nine individual tribes. For example, the first volume (photos from which are featured in this post) is titled “Apache, Jicarillas, Navaho.”

When Curtis was publishing his volumes, he had difficulty obtaining subscribers, and as a result, his work was largely forgotten before it was even finished. In recent years, however, his sepia-toned photographs of Native Americans have experienced something of a revival.

Although Curtis has been criticized for staging and doctoring photos to present a very specific, romanticized version of native peoples, these photos nonetheless provide a glimpse into the lives of Native Americans in the early twentieth century. Contemporary author N. Scott Momaday has said of the photographs:

“[T]he world of these photographs is one in which breadth and luminosity are indispensable dimensions of spirit and reality. This definitive collection of the Curtis photographs is an American treasure. They are not artifacts or cultural exhibits; they are not fossil records or curiosities. They are validations of an important and unique moment in the evolution of an American identity. That moment is forever ours, and it is indeed a sacred legacy.”

N. Scott Momaday

Curtis’ volumes and their extensive photographs have been digitized in their entirety and made available at Northwestern University Library’s Edward S. Curtis digital collection.