Race, HIV/AIDS, and Health Care Access in 1980s St. Louis

In conjunction with programs at The Griot Museum of Black History, Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis is taking a closer look at the history of HIV/AIDS and sexual health in St. Louis. This post by Mapping Project intern Eliza Murray focuses on the 1980s.

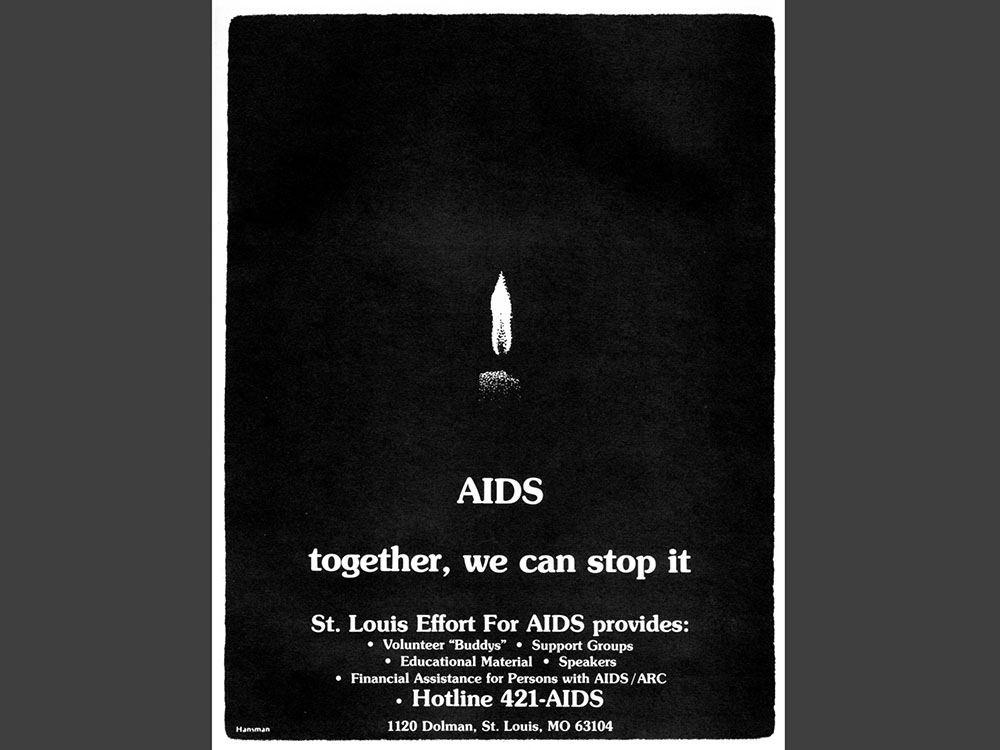

In the mid-1980s, efforts to understand, treat, and prevent HIV/AIDS were still in their infancy. Facing this challenge, St. Louisans worked to fashion a network of support that addressed the roots of stigma, called attention to the city’s inadequate health care system, and promoted HIV/AIDS prevention for Black LGBTQ residents.

Awareness and Advocacy

In October 1986, the St. Louis Effort for AIDS (EFA) hosted a panel discussion with the National Minority AIDS Council (NMAC). At this program Dr. Arthur Brewer, chair of the NMAC, pushed back on the assertion that HIV/AIDS was a “white, homosexual disease” and warned, “AIDS has been an epidemic in the black community from the very beginning, but because we refuse to talk about it and refuse to educate ourselves about the disease, we will continue to die in large numbers.”[1]

Writing about the event for the St. Louis American, journalist Patricia Washington explored the social and political issues of the growing epidemic under the headline, “AIDS TARGETS BLACKS.” Along with statistics, and coverage of the EFA event, she also contacted the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays (NCBLG). NCBLG member Gil Gerald drew attention to the harm of stigma, noting, “Because blacks deny homosexuality as a problem in their community, they deny AIDS, but what they don’t realize is that the disease is affecting heterosexuals increasingly and on a national level it is caused primarily by IV drug users.”[2]

Dr. Rensow Scherer, a physician at Chicago’s Cook County Hospital AIDS clinic, noted a lack of federal funding, particularly for smaller centers and those in the Midwest. Scherer’s clinic was not alone. The St. Louis Regional Medical Center was also lacking funding for people living with HIV/AIDS.

Access to Health Care in St. Louis

In the 1980s people in St. Louis city and county, and particularly people who were Black and LGBTQ, faced limited public health care options. This inevitably led to less testing and less treatment for people living with HIV/AIDS.

Homer G. Phillips Hospital – a once-thriving hospital, and historic training center for African American physicians and nurses, in the historic Ville neighborhood, was closed by the city in 1979. City Hospital became the only remaining option for people unable to afford private medical care, although it too was closed in 1985. In their place was the St. Louis Regional Medical Center (“Regional”) at 5535 Delmar Boulevard, jointly operated by St. Louis City and County [5].

Activists including Walle Amusa of the Campaign for Human Dignity, and Zenobia Thompson, nurse and co-chair of Health Care is a Human Right Coalition (HCHRC), called attention to the inadequacies of St. Louis’ health care options through letters, petitions, picketing, and lawsuits. Located in the city, Regional was hard to reach for a large portion of county residents. Herman Blumenthal, co-chair of HCHRC, wrote in the St. Louis American, “County patients represent only about 13 percent of Regional’s occupancy whereas the original agreement between the county and the hospital anticipated occupancy of 30 percent.”[3] In 1987, HCHRC sued Regional in state circuit court to prevent physical expansion of the Delmar facility, but the court ruled in Regional’s favor.

And HCHRC members coordinated with other regional health care organizations to support health care access and education about HIV/AIDS. Together with the Human Rights Office of the Catholic Archdiocese, Planned Parenthood of St. Louis, the Family Care Center of Carondelet, St. Louis Effort for AIDS, and others, HCHRC signed a statement opposing federal funding restriction on AIDS education. The bill, sponsored by US Senator Jesse Helms, banned “federal financing for any organization that advocates homosexuality while teaching about AIDS.”[4] Although passed in 1987, it was replaced by Congress with a less discriminatory bill the following year.

Efforts by activists both locally and nationally were needed to fight social stigmas, pressure politicians on funding public health programs, and advocate for people living with HIV/AIDS.

SOURCES:

[1] Washington, Patricia. “AIDS Targeting Blacks” St. Louis American, November 5, 1986.

[2] Washington, “AIDS Targeting Blacks” St. Louis American, November 5, 1986.

[3] Blumenthal, Herman T. “Definitive Response to Health Care Matters” St. Louis American, February 26, 1987.

[4] Manor, Robert. “11 Groups Oppose Bill on AIDS Education” St. Louis American, November 5, 1987.

[5] Connolly, Ceci. “St. Louis Offers The Long View.” Washington Post, June 24, 2001.

EXPLORE MORE:

- Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis. Political Timeline.

- Joyce Marie Fitzpatrick and Brian Shackelford. “The Color of Medicine.” 2018. https://www.thecolorofmedicine.com/ Documentary film about Homer G. Phillips Hospital.

- Jonathan Bailey. “As Proud of Our Gayness As We Are of Our Blackness” Black Perspectives, Feb. 24, 2016. https://www.aaihs.org/as-proud-of-our-gayness/ An overview about the National Coalition of Black Lesbians and Gays.

Completed as part of an internship with the Julian Edison Department of Special Collections, under direction of Miranda Rectenwald.