No Elvis, Beatles, or the Rolling Stones: A Collector’s Journey

“A Collector’s Journey” is a companion essay to the exhibition Pasted Youth: Analog Design of the Punk Movement, currently on view in the Thomas Gallery at John M. Olin Library through July 7, 2024.

The summer of 1977 was one of the most formative periods of my life. From the first encounter with punk rock, the music, posters, and fashion immediately struck me. The broader popular culture of the mid-1970s held zero interest for me. I detested the pretensions of prog rock, whose often shapeless, indulgent music dominated the airwaves then. Except for The Who, I had no music to call my own. Hearing the first Clash record in June 1977 flipped a switch in my brain and my musical world was transformed.

My father’s family lived in London, and every summer during my teens I would visit relatives for several weeks. My cousin, John Krivine, was immersed in punk fashion, having founded the King’s Road shop Acme Attractions with Steph Raynor in the early 1970s, followed by BOY in 1977. I spent several days in the shop that July, and while John conducted BOY business I would observe the exotic (in some instances, rather scary) punk patrons in the shop. Many afternoons I would walk up and down the King’s Road, going to record shops and, with trepidation, step through the entrance of Seditionaries, the ground zero for punk fashion. For a 16-year-old lacking self-confidence and an ocean away from his suburban home, Seditionaries was an awesome and menacing place.

By the time I returned to Briarcliff Manor (my hometown within New York City’s commuter belt) in early September 1977, I had become a devout proselytizer for punk. Kitted out with oxblood DMs, blue suede brothel creepers, several BOY and Seditionaries shirts, and bondage zipper trousers, I was convinced that within weeks, punk was going to sweep America and I would be credited for being the cool “first mover” in Briarcliff. How much more deluded could I have been? My classmates were bemused and made a few sarcastic comments but basically tolerated my obsession with punk. A few years later, I spent my junior year at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England. UEA was part of the university touring circuit and nearly every exciting British band that passed through Norwich performed there or at local clubs. A wealth of “new wave” musical creativity, the Cure, a very young U2, Altered Images, the Au Pairs, Echo & the Bunnymen, the Jam, Madness, and the Skids.

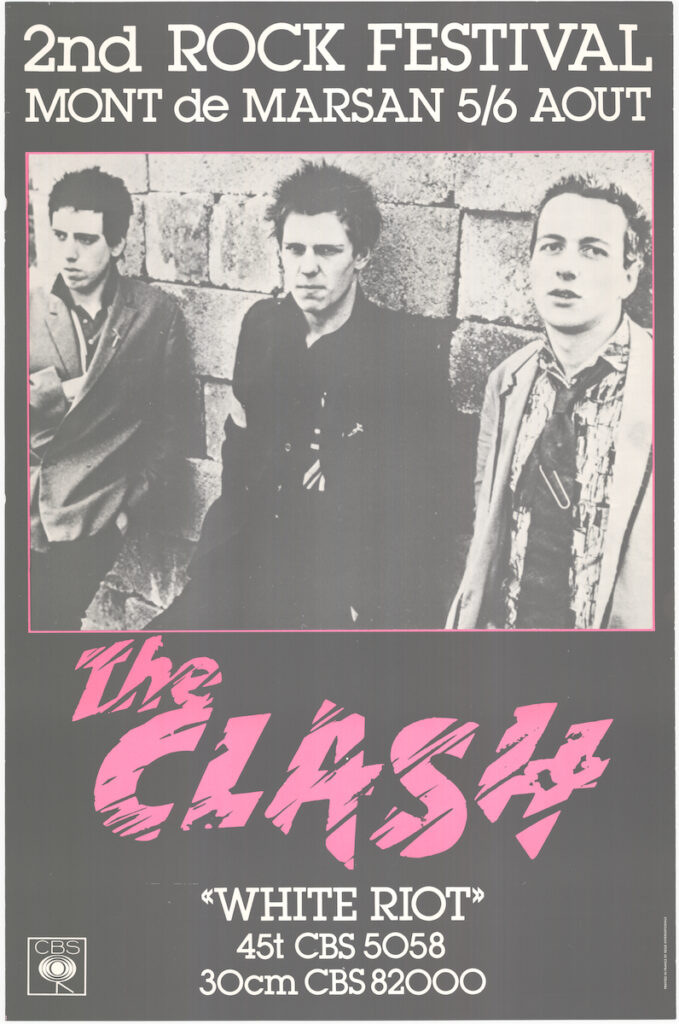

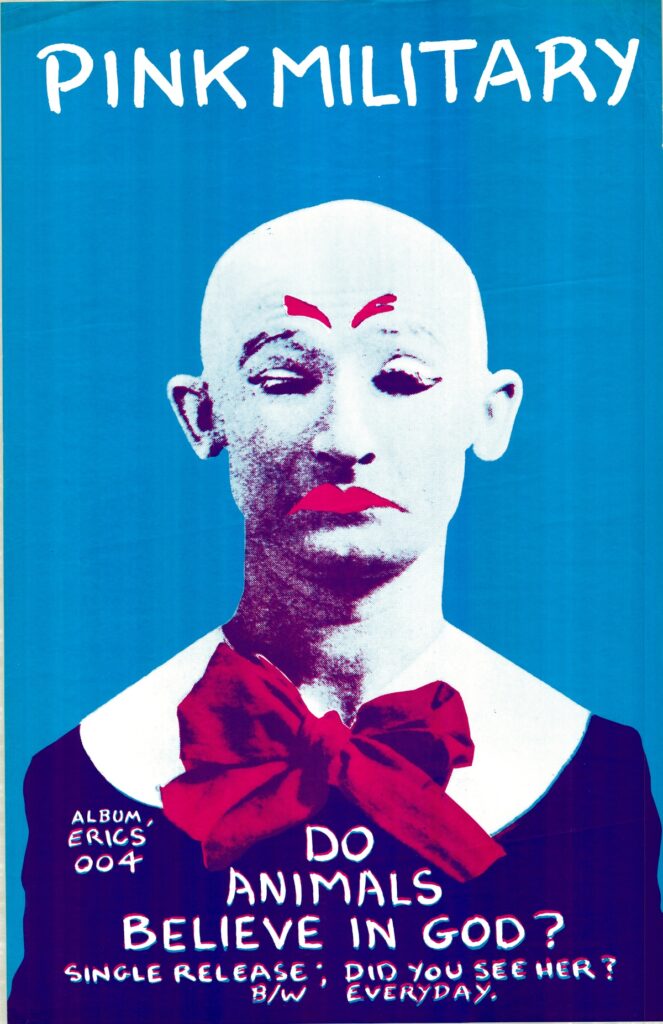

After university, I continued to add to my collection, for both a love for the music and an appreciation of the artistry of countless punk, new wave, and post-punk poster designs. I was compelled to devote as much time and effort as possible to my collection. The fashion, graphic designs, the intense irritation punk provoked in the older generation, and, of course, the music itself, all fueled my passion. Punk sonically pulsates; it has velocity, aggression, and humor. Punk rejects hypocrisy and pretense. There are no entry requirements, no barriers to prevent you from joining a band and making a racket. A rudimentary command of guitar, drumming, or even singing is all you need (as I can well attest: a dreadful guitarist, which didn’t stop me from playing in Bloody Hell).

Graphic design and music in the punk era were closely fused, particularly in Britain. Musicians such as Viv Albertine, Adam Ant, Ian Dury, John Foxx, Mick Jones, Glen Matlock, and Paul Simonon all studied at art schools before forming bands. The widely accepted narrative of punk’s spontaneous, untutored DIY impulse—while true for the music—is largely inaccurate regarding the designs. Many of the young Britons who would become designers or join bands came up through art colleges being exposed to art, graphic design, and fashion. The T-shirts and trousers stocked by BOY and Seditionaries—as well as the gear created by the bands themselves—were embossed with slogans, patches, typography, and symbols, Vivienne Westwood created several hand-made t-shirts, which fused Sex Pistols lyrics with provocative imagery. From the very start, the music and graphics of punk were merged into a symbiotic dance.

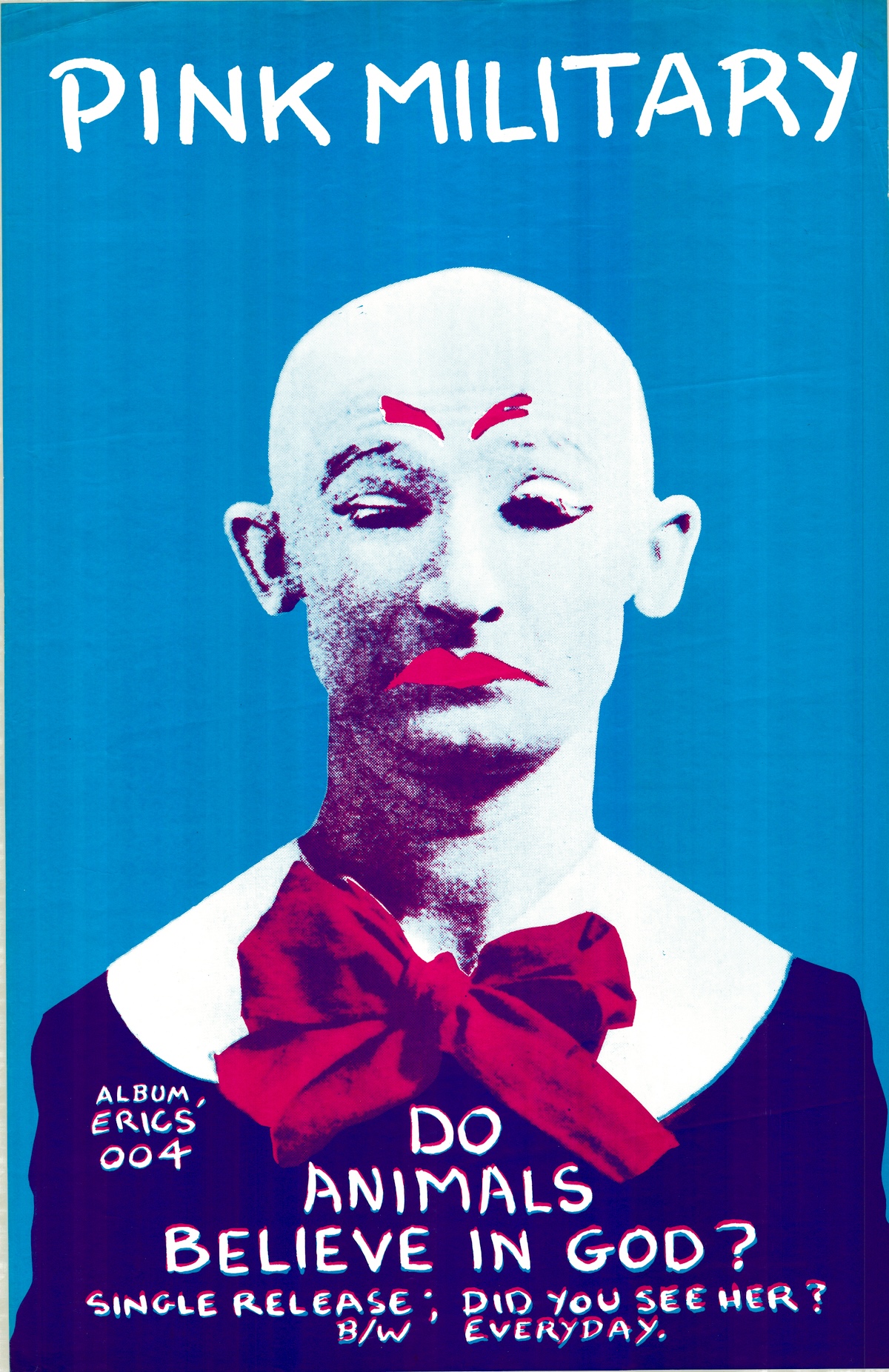

In Julien Temple’s film The Clash: New Year’s Day ’77, we see The Clash customizing their boiler suits and shirts in a dank London taxi repair garage, using stencils and spray-paint guns. The resulting clothes can be seen worn by the band on the cover photo of the single “White Riot.” The Clash epitomize the idea of Gesamtkunstwerk—a creation that synthesizes the musical, theatrical, and visual arts—we see how the band’s music (the inaugural gig at the Roxy), graphic art (Paul Simonon’s mural on the wall of their Rehearsal Rehearsals practice studio), and their self-made clothing all fused seamlessly.

During the first wave of punk, the fashion had vitality and immediacy from multiple, cross-pollinating sources: clothing designers, the bands and the DIY-inspired punks going to the clubs. Many distinct looks came from individuals on the scene Poly Styrene, Jordan, Siouxsie Sioux, as well as bands mining art historical movements in a search to invent a new look for themselves such as Generation X (Constructivism), The Sex Pistols (the Situationists), the Buzzcocks (Mondrian), and The Jam (Pop Art).

In a time before social media, designs in print were the public face of the music, the design often as iconic as the music itself. Many British punk, new wave, and post-punk musicians forged enduring partnerships with individual graphic designers and photographers: Barney Bubbles and Elvis Costello; Mike Coles and Killing Joke; Raymond Pettibon and Black Flag; Malcolm Garrett and Buzzcocks; Jamie Reid and the Sex Pistols; Peter Saville and Joy Division/New Order; Gee Vaucher /Dave King and Crass.

The music represented in Pasted Youth creates a platform for exuberant and visually arresting postmodern graphic designs of the twentieth century. If visitors to the exhibition experience even a fraction of the excitement and exhilaration these posters and artifacts have given me, I will be thrilled!

Andrew Krivine, who lent posters and other materials for the exhibition Pasted Youth: Analog Design of the Punk Movement, has been collecting punk since the 1970s and is based in New York City. He is still growing his collection and it is featured in his two books: Too Fast to Live Too Young to Die: Punk & post-punk graphics 1976-1986 and Reversing Into The Future: New Wave Graphics 1977–1990.