Nina Seavey on My Fugitive and Working with Archives

Nina Gilden Seavey is an award-winning documentarian and podcaster and Research Professor of History and Media and Public Affairs at George Washington University. Her most recent project, My Fugitive, is an 8-episode podcast produced by Pineapple Street Studios that delves into the circumstances surrounding the day the ROTC building at Washington University burned to the ground in 1970, and what happened to Howard Mechanic, the young man arrested in connection with the fire who became one of the longest-running fugitives in US history. Seavey’s search for answers unearths connections to FBI surveillance, the assassination of civil rights icons, conspiracy theories, and much more.

Seavey will be speaking with Sarah Fenske, host of St. Louis Public Radio’s “St. Louis on the Air,” on Saturday, November 13 at 4 pm as part of the St. Louis International Film Festival. In advance of her visit to St. Louis, the Libraries reached out to Seavey to learn more about how her research in our archives impacted her work.

Can you describe how you started using the archives at Washington University Libraries to inform My Fugitive?

When a documentarian starts any new project they need to throw the door open as widely as possible. The Washington University archive was an immediate “go-to” on my list of potential resources, for one interesting reason: WashU never backed away from what had happened in the wake of the night of May 4, 1970. Many institutions might have tried to bury the unrest and repression that occurred—fearing the potential damage that such chaos might have caused to its long-term reputation. But WashU embraced what had happened. In particular, the flight of Howard Mechanic meant that the legacy of the campus protests of the 1960s and ’70s endured well into the twenty-first century. The university clearly saw that turmoil as part of its legitimate history, so they have invested significant time and resources to collecting resources, specifically many varieties of primary resources, necessary to document what is not just a critical period in the institution’s past, but in the history of dissent in the United States.

There were rich materials in the Dan Bolef Papers, oral histories conducted under the tutelage of Professors Henry Berger and Wayne Fields, and FBI files donated by former students who had made FOIA requests for their Bureau Main Files as they had been activists at that time. I went back into my emails and located communications with University Archivists Carole Prietto and Sonya Rooney dating back to 2011—an entire decade of research! Initially, I requested a senior honors thesis by former history undergraduate Daniel Gray Thomas for his senior honors thesis Birds of Passage (there is now a Fellowship for Social Justice named for his thesis), and that document served as a basic road map for me as to what- happened at Washington University at this seminal time in the university’s past.

But my main point of contact since 2013, and throughout this long investigative process, was Miranda Rectenwald. She has such a detailed grasp of what is in the university’s archives and how those materials might help to further my research. I love archivists and felt not a small twinge of guilt when I had to sue the National Archives in Seavey v. Department of Justice et al (which included the FBI, the CIA, and the National Archives) for release of documents central to telling this complex story.

What were the biggest challenges along the way in terms of finding information or getting what you needed to tell the story you wanted to tell?

The biggest impediment I encountered at Washington University (there were many greater obstacles in dealing with the federal government) was the lack of access to back issues of Student Life. As I researched a story that was so centrally located in what students were doing and thinking from 1967-1971, not having a searchable online resource for the student newspaper was vexing.

Ultimately my research associate Charles Richter located a year-by-year compendium of PDFs of the newspaper, but using that meant knowing what year we were looking for a certain subject matter and the relative time of year that such information might have appeared in the paper. While we did optical character recognition (OCR) on hundreds of thousands of pages of files, it is not a process that is particularly successful with PDFs that have various styles and sizes of fonts. Our inability to search the newspaper seriously limited our ability to ferret out critical information and storylines.

Oddly enough, when I won my lawsuit against the Department of Justice, the government released a treasure trove of copies of what was being published in Student Life, as the FBI was keeping extraordinarily close track of what was being written in the paper and by whom. As a method of research, I wouldn’t rely on such invasive techniques by the government and would hope that the university would allocate sufficient funding for the digitization of the entire archive of Student Life. It is an invaluable resource reflecting not only what students at WashU have been concerned about on campus, but how the university has interacted with St. Louis, and the nation, writ large.

What was something surprising that you learned or found in the University’s archive materials?

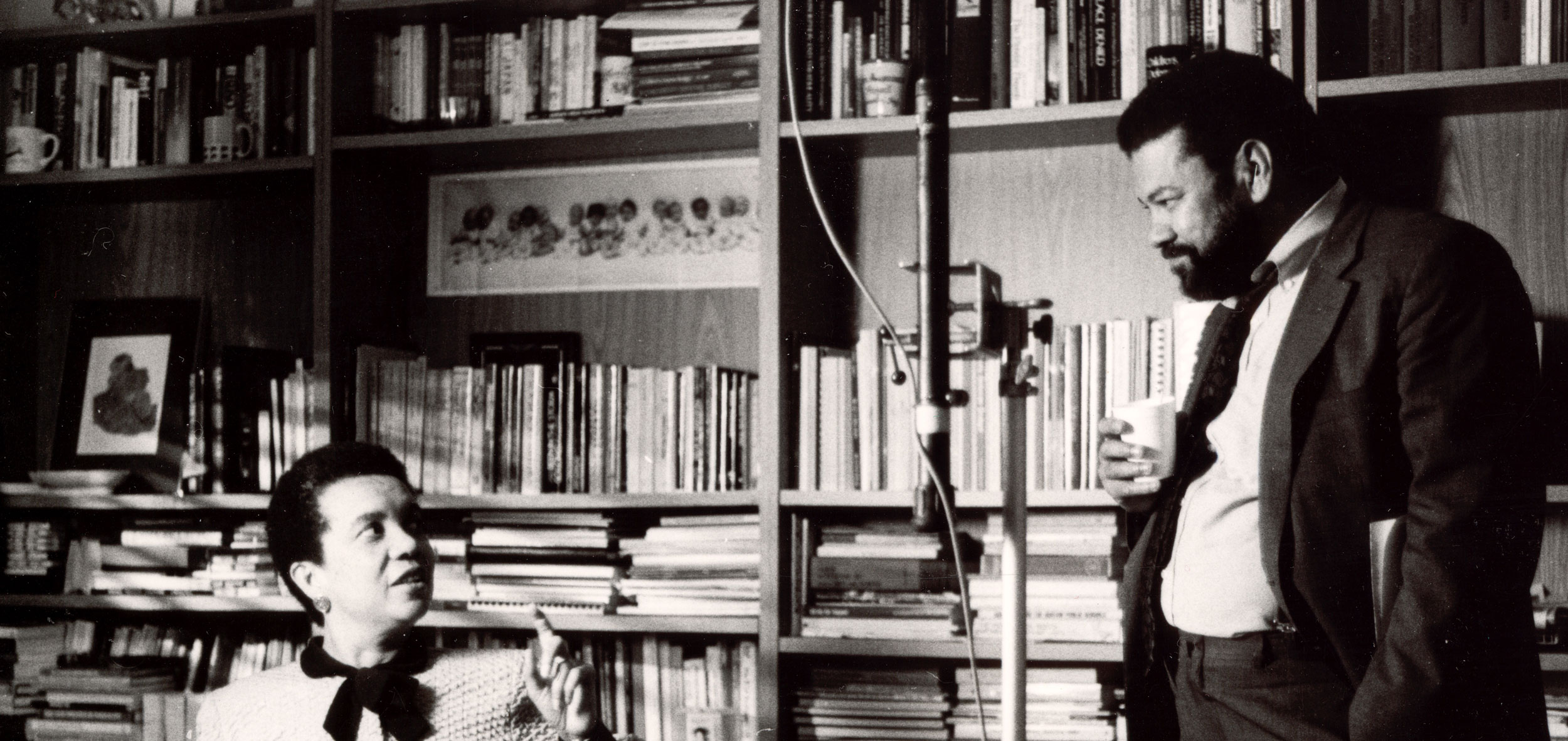

I thought it was kismet when I found the interview from Burke Marshall, former Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, in the Eyes on the Prize Henry Hampton Collection in the Film and Media Archive. I was very close with Henry, especially at the end of his life, and I miss him so much to this day. We used that tape in episode 3 of My Fugitive. It was such serendipity that his collection had the exact tape I was hoping to find like a needle in a haystack in every archive throughout the US. And there it was at Washington University! It seemed to me that Henry was anointing this new project, which was such a personal joy of connection for me.

What advice would you give to others who want to take advantage of primary resources to conduct this type of research?

Time. Give yourself plenty of time. You need time to not only research the materials once you’ve received them but time to make your request and have it fulfilled. We live in an era when we expect everything the way Amazon delivers to us – “Next Day Delivery!” but that’s not how archives work. They are driven by people who have many requests in addition to the one you’ve made. Your request might take some digging to locate, perhaps some consultation with colleagues, and then some time to duplicate. So, giving yourself plenty of time to have a request fulfilled is key to ensuring the success of your research.

And most of all, be kind to your archivist. They are national treasures.