NEXT Awardee’s Poetry Shaped by Slavery Archives in The Netherlands

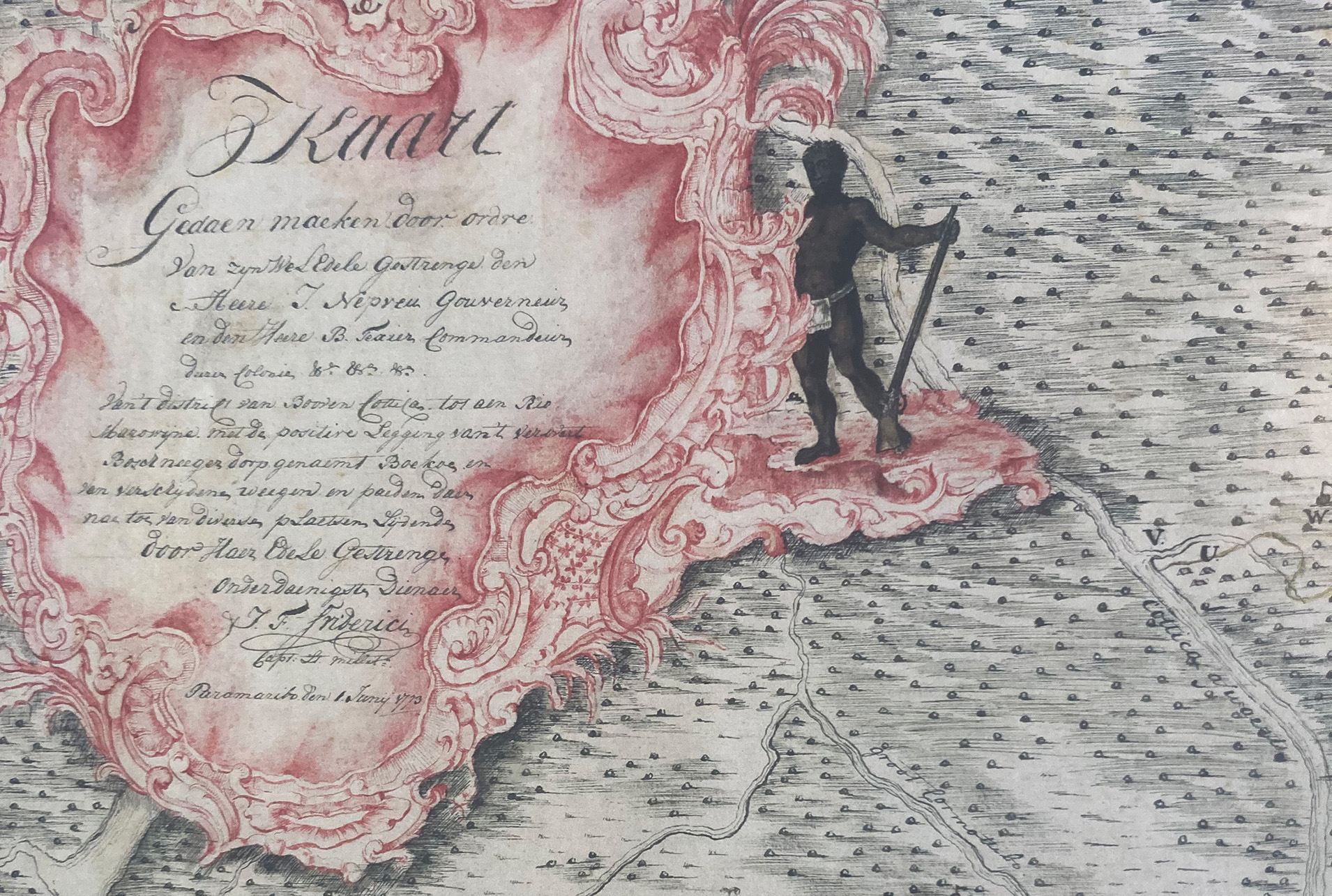

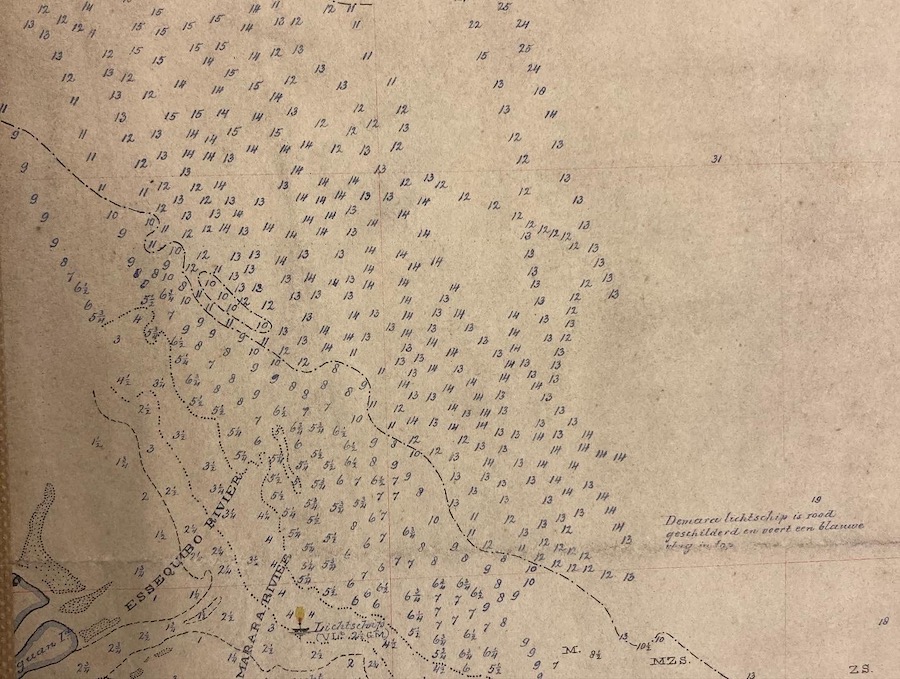

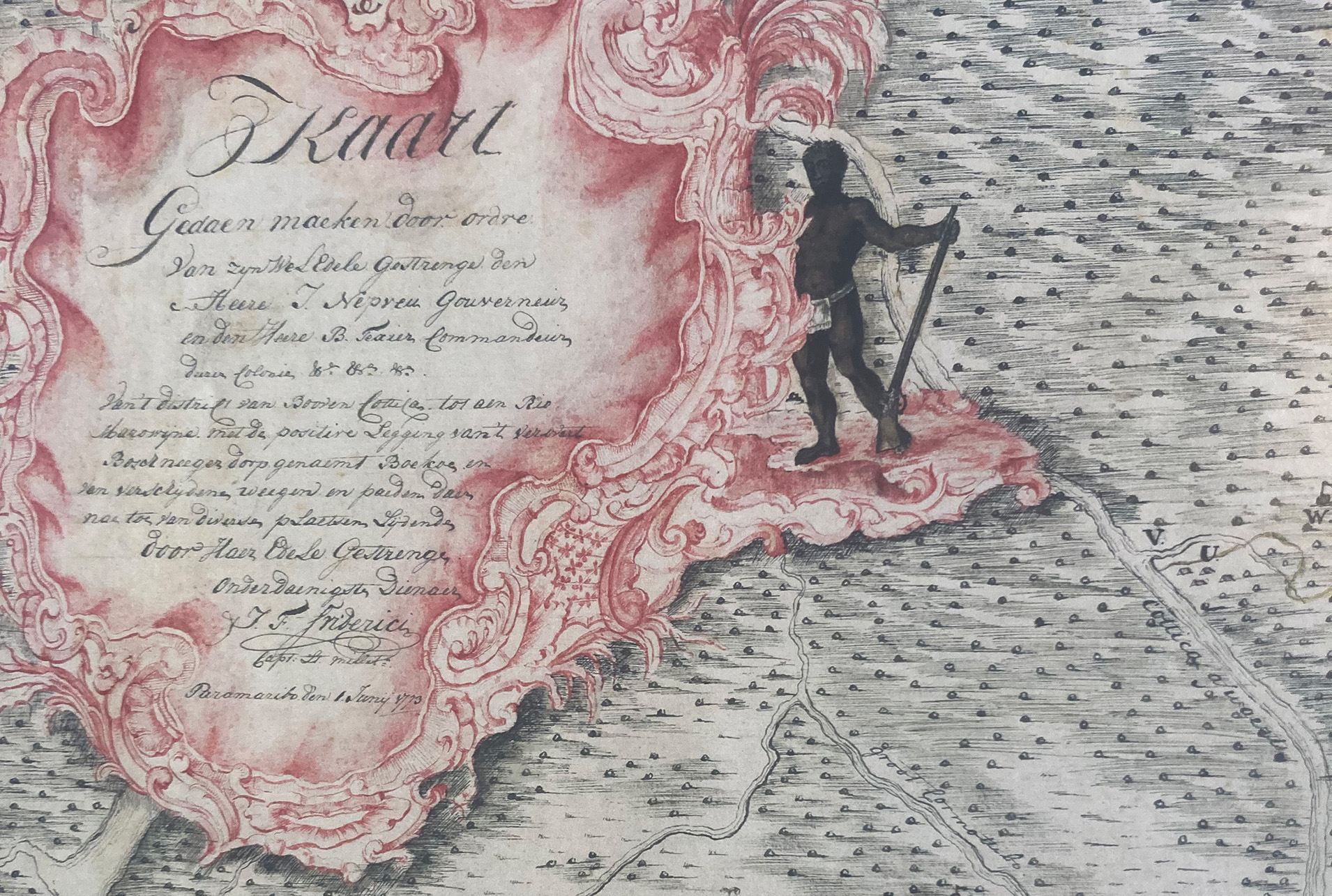

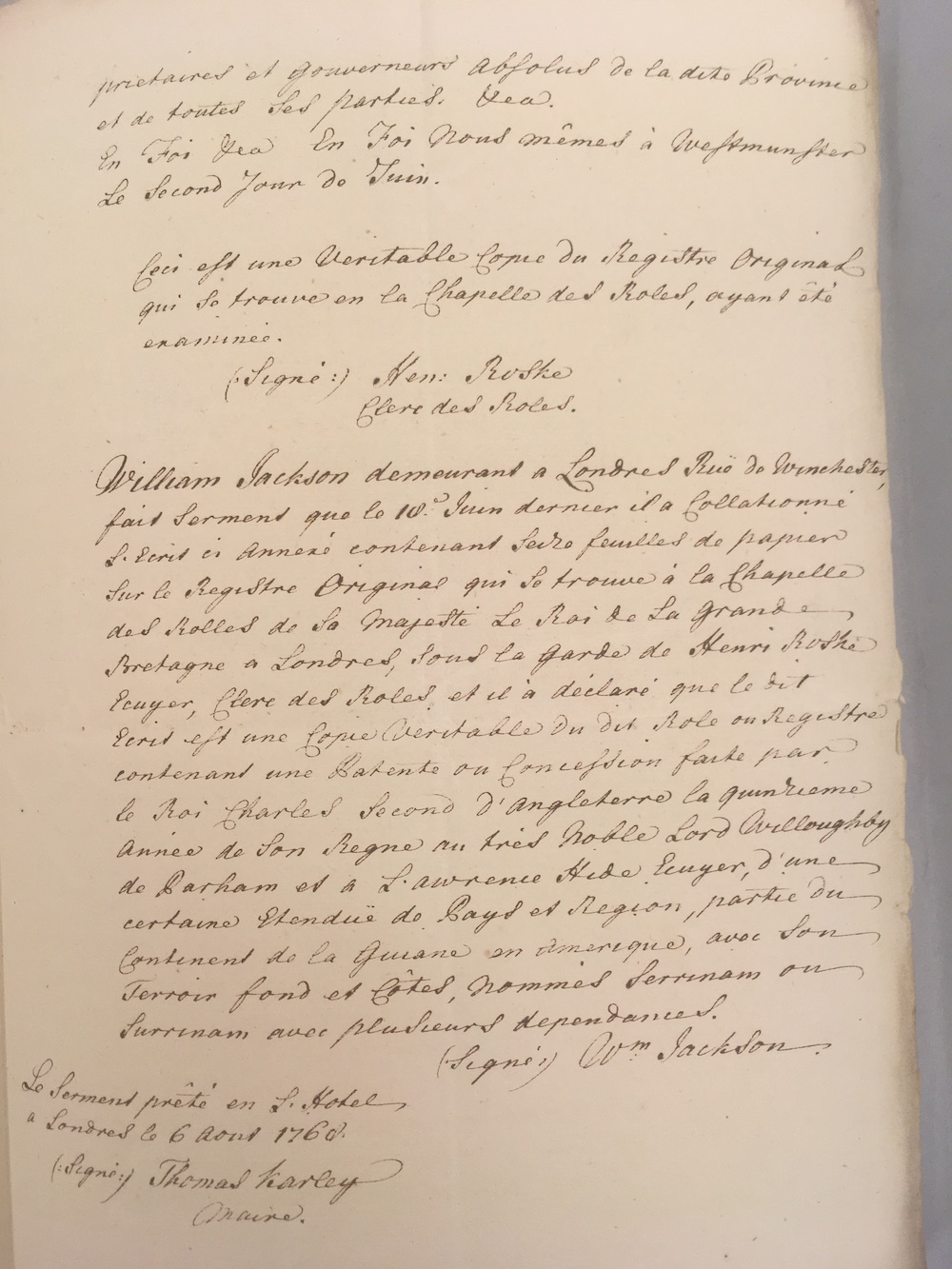

The goal of my trip, funded by the Newman Exploration Travel Award, was to interrogate documents in the National Archives of the Netherlands, located in The Hague. These relate to the Dutch slave trade and a specific slave ship that sank in the Marijowine River, bordering Suriname and French Guyana. Ultimately, I want to use this new knowledge to create a poetry project.

There were four documents related to the sinking of the Luesden—a letter from a captain, a governor’s journal, a log of all the trips the Leusden took, and a report of the disaster by the Dutch West India Company commission.

This is a brief part of the governor’s journal dated January 4, 1738:

Arrived Jochem Outjes, having sailed the West Ind. Compie [sic] Ship Leusden, coming with his ship’s boat and sloop with all the sailors and 16 slaves from the Maroyweijne, where he lost his ship with an armament of slaves large 671 heads, of which 16 reported slaves have been saved.

While the governor’s report is banal, I was curious about the sixteen slaves who survived—it was surprising to me that they were sailed back to Elmina.

Elmina famously housed the “door of no return”—a door that millions of Africans passed through before crossing the Atlantic. Dionne Brands writes about how after an African passes through that door, they no longer exist as human, they enter a different category of being—they exist as a slave. It is an incredibly rare occasion that an enslaved person would ever pass back through that door. It is even possible that only these sixteen slaves were some of the only to return out of millions. I wonder about the conditions that lead to this return; if the slaves were sent on another ship after sailing across the Atlantic and back, or if the slaves were no longer slaves after their return.

Unfortunately, the list of passengers was not held in the archives; it may have not survived history, so I will never know what happened to these passengers who returned to the door of no return. Still, reading the log opened up my thinking about the disaster and gave me more poetic space to build a world around the ship’s sinking and its aftermath.

I wrote a poem about my frustration that arose out of not being able to understand these people’s lives—about being limited by the expansive archive. And, I also wrote to acknowledge that their stories exist and do have an impact and are a part of our world even if no one will ever know who they are, never read their stories, or never again hear their voices:

frederika aallo

adiana diana aallo debecca aallo

daniel january aallo

i don’t understand

why but once you make a sound

the vibrations are absorbed

into the material world and they stay

there forever

there are voices

and car horns and doorbells

from yesterday and years ago

in the mud

in the walls

of your apartment

i want the aallos

to tell me a story i can hear

but they won’t so i read their names

to a door

and then

i open it

After translating the four documents about the Leusden with the help of a friend in Belgium who I stayed with for a long part of the trip, I looked at other documents about the Marijowine River. I learned about the Boni Wars through letters written back and forth from Dutch and French officials on opposite sides of the river. Transcribing and translating these letters were very difficult because the handwriting was hard to read and in a language I don’t know very well, but still, with help, I translated and transcribed five letters from Dutch and French officers discussing the beginnings of the Boni Wars.

This is a section of a particularly illuminating letter, written by a French official:

In fact, our efforts, joined to theirs, would not be sufficient to prevent the negroes from migrating. In the meantime, our hostile demonstrations would only serve to siruter [sic] them against us, and to expose us to the effects of their vengeance; even if we succeeded in extirpating a few hordes [of fugitive slaves], they would soon be replaced by those who are buried in the immense forests that are found in these regions, so that we would be exposing ourselves to an eternal war with a nation that has not yet offended us, and that the [fugitive slaves] themselves represent to us as barbaric, cruel, and treacherous.

This letter is dated September 23, 1777. Before reading this document and others like it, I was unaware of the mass slave uprising along the border of Suriname and the powerful fugitive communities that existed along the river. Not only did slaves revolt, but they also controlled areas of French Guyana—French officers could do nothing to subdue them. I’d never seen slavery written about in this way before my trip—first-hand terror from the perspective of the master. It was exciting to learn more about the Boni Wars and the history of the Marowijne River through this primary source material that I stumbled on through research of the Leusden.

While I spent the bulk of my trip traveling back and forth between Belgium and the Netherlands, I also had the chance to visit Poland—where my family is from—Athens, and Prague. All places I have never been to before! Now, I feel like I have a fuller understanding not only of the Leusden, the Marowijne River, and the Boni Wars, but also of my family’s Polish history, along with the unknowable—my Black history.

All photos courtesy of Asha Futterman.