NEXT Awardee Studies Architecture in Italy and Switzerland

“Mathematics is the language in which God has written the universe.” – Galileo Galilei.

“Music is the universal language of mankind.” – Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

Over my month in Northern Italy and Switzerland, I played seven different pianos. A fact that may sound tangential to the study of architecture but that architecture itself, as I have come to learn, is the universal synthesis of music and mathematics: the third language spoken and understood by humankind. A method of communication at once deliberately developed and instinctively understood, architecture is the convergence of emotion and reason, of dream and solution. Without music it is mechanics, and without mathematics it is fantasy.

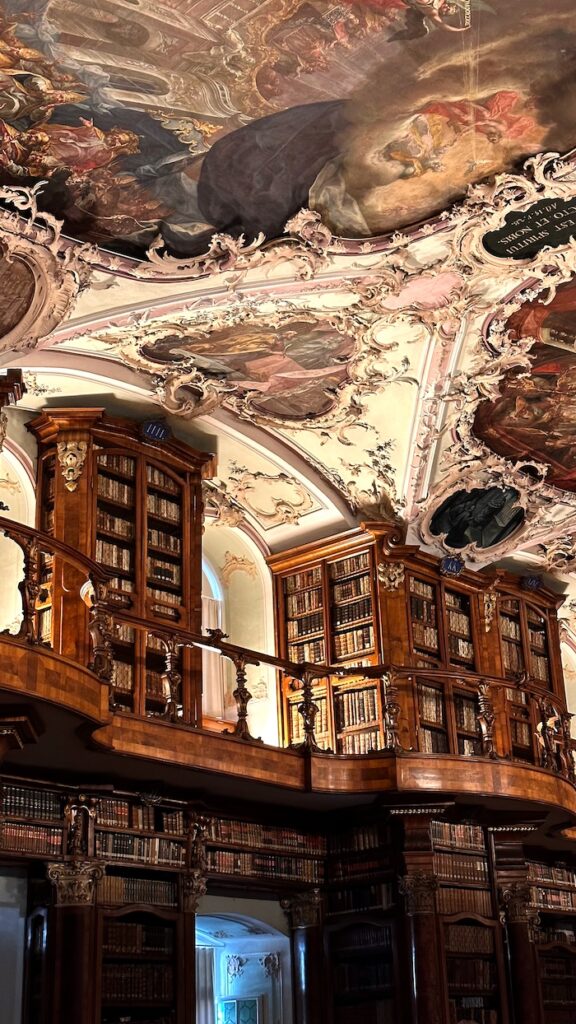

The architecture I studied—spanning sixteen cities from the rolling plains of Tuscany to the misty peaks of Alpnach—illustrated this idea in subtle ways. The narrow alleys of Tirano, passing under elevated skywalks from one crumbling building to the next, spoke about the need for covered passage during winter blizzards, but also of the adventure of discovery. The baroque abbeys of St. Gallen creaked and groaned underfoot, fatigued from their centuries of housing ancient tombs, but still dutifully transporting their visitors to the mystical worlds painted across their ceilings. The tallest spires and humblest homesteads, grandest arches and simplest markets, revealed the push and pull of artistry and utility—and the best rendered them inseparable.

When I was not devising mildly aggrandizing analogies, I spent a good amount of time eating alone (admittedly, the two likely go hand in hand). Not in a sad, lonely manner, but rather in a peaceful, contemplative one.

Dinner evolved from the most social hour to the least, and I found myself slowing down in an unexpected but welcome way. People-watching became my favorite pastime, especially in such fashionable cities as Milan and Zurich; the real Italians were always distinguishable from tourists by a combination of denim bottoms that did not go all the way down their legs (either jorts or rolled-up pants), no-show socks hidden inside beat up white Adidas, and a complete disregard of the two-thousand-year-old architectural masterpiece they were hurrying past. That isn’t to say I ate every meal alone. The many international friends I made our shared dinners into some of the best I’ve ever had.

But, particularly in less popular cities lacking communal hostels for accommodation, I found myself without company whether I wanted it or not. In these common instances, Italian waitstaff was consistently the kindest I’ve had the pleasure of interacting with—during my travels, I consumed more free drinks than I paid for. How many of these were pity cocktails as I sat alone in a restaurant full of couples in Venice? A not insignificant amount.

Indeed, Italian waitstaff was unequivocally charming, but, unfortunately, I cannot say the same of their Swiss counterparts. Not because they were rude by any stretch, but rather because I regretfully enjoyed only two waited meals during my eleven days in the country. The cost of everything—particularly food—is so astronomically high in the second most expensive country in the world, that Marco, a thirty-seven-year-old from Lugano, catches the bus to Italy for weekly groceries. A Margherita pizza with a menu price of six euro and fifty in Italy was marked at the USD equivalent of $24 not thirty minutes on the other side of the border. So, while I can personally verify the Swiss’s mastery of dairy products and scaling 54-degree inclines in sandals, I cannot make any trustworthy conjectures regarding their hospitality.

During periods of isolation in Italy, I strolled the lakeside promenades of midnight Menaggio, listening to wavelets lap the shore and watching moonlight flicker over countless ephemeral ripples. A week later, I rested at the peak of the Swiss Alps to catch my breath after a difficult climb only to have it snatched away by the sight of sparrows diving amongst the crags, tiny dancers moving across the most sublime painted backdrop anyone has ever laid eyes on. Behind me, all of Switzerland curved away into the horizon, towns and forests and rivers and lakes patterning an endless mottled camouflage. I felt whatever it was to be the opposite of alone, despite being more isolated there than anywhere I had ever been. I had in my employ neither cell service nor companion, on the far side of a world upon which not a single person knew my whereabouts. Maybe I smiled, maybe I cried, though no one but I can say.

Here, I understood the connection to nature so touted by modern architects, but in a different light. The farmsteads dotting the valley some five thousand feet below were not studies in how to draw sunlight into their otherwise gloomy interiors. They were not showcases of the Venturi effect, or independent solar farms, or passively regulating structures. There was no clunky theory, no ultra-luxe technological application. There were just unblinking windows aimed at peaks and pines, small balconies brightened with daisies and colorful clothes set out to dry, and the languid, idyllic puffing of smoke from brick chimneys. In their simplicity, in their faithfulness to the mathematics governing their design, these small, simple houses sang purer music than the tallest glass skyscrapers in the world.

At times, it really did feel like I had stumbled my way into an epic. I fought off snakes (ran screaming down a hillside after narrowly avoiding a bite), bartered passage through perilous canyons (didn’t have enough cash to afford a bus ticket), deployed espionage (convinced people I was Sicilian for fun), and watched fortresses crumble (no embellishment necessary—it was incredible). I infiltrated castles and explored crypts, heard the chime of church bells, and tasted homemade pesto made with basil and pistachios. I hiked an average of nine miles a day for a month.

It was easy to become enraptured with the fantasy. From lakes gleaming turquoise with natural clays to medieval churches climbing high above twisting cobblestone streets, the possibility of dragons never seemed too unfathomable. In fact, one of the mountains I hiked once housed a dragon before a saint dispelled it. But even when I wasn’t in an outlandishly picturesque landscape or millennia-old town, the least remarkable of streets was more magical than entire swaths of our brick-and-asphalt cities.

But still, in the back of my mind was the surreal knowledge that I was witness to the source material. Before Shakespeare, Voltaire, Vivaldi, and R. R. Martin was this. No spells are needed. The magic was already there. The greats are simply those who captured it in a jar and brought it home.

You, dear reader, have heard the term “the pictures don’t do it justice” a thousand times. A world described in picture and effect, no matter how big the screen, holds no candle to the majesty of reality. Why that is so has to do with issues of scale and perspective—the camera simply cannot fathom how cavernous the apse, how deep the nave, how complex the frieze truly is.

I was never a fan of Corbusier. Even with an understanding of his professed goals of intentional dematerialization and the rejection of established architectural vocabularies, his radical (and incredibly loud) use of color and defamiliarized forms repelled me even as I acknowledged his contributions to the field. That is until I visited his work in his home country.

What Corbusier understood—the magic he captured in a jar and brought home—was that sense of adventure. The admittedly bizarre amalgamation of forms faded away, foregrounded instead by quirky decisions and hidden nooks. Port doors for seemingly no reason, human-height openings in bookshelves, indistinguishable barriers between interior and exterior, and sculptural roofs suspended over structure. Pavilion Le Corbusier, an art museum in Zurich, molded space masterfully to its grid and gave the expansive bubble surprising freedom even confined as it was. The Pavilion was discovery as much as it was exhibition, and for that reason, it was truly an enjoyable space to visit (even if it was baking in the sun).

I hate to give Corbusier the satisfaction of hijacking yet another conclusion to an essay, so I will close with this: To those at the Newman Exploration Travel Fund who provided me with this opportunity to pursue my academic research, I am profoundly thankful. The ability to see and touch, at my own pace and with time to reflect, the architecture that has shaped my reality and yours, and the chance to formulate my positions, however uninformed I still may feel (I am only just beginning, after all), has been an experience of great impact to my education and person. Though I have enjoyed playing the piano for years now, I am at a stage in my architectural education where I can only just make sense of the music rather than compose it of my own accord. But through this last month, I have felt myself stepping ever closer to becoming the thoughtful, precise, informed designer I have so avidly yearned to be.

Plus, I learned to make gelato.