NEXT Awardee Explores Archives of Munari and Montessori in Italy

The shimmering peaks of the Italian Alps that I traversed on the flight to Milan belied the blistering heat that awaited me on the cobblestone below. The skyscrapers of northern Milan radiated the hot energy of the Italian sun and the city’s industrial core, while gusts of thick air, courtesy of the constant swish of scooters, lent a sense of frantic bustle to my daily walks. My experience with picture books since childhood brought me to Milan during this particularly warm June. The heat drove me out of my sun-baked apartment in search of a spot of shady grass, and as is the case in many major metropolitan centers, there was little to be found.

The striking architectural wonder, Bosco Verticale, a modern residential tower sown with a scaffolding of tree-filled terraces, both delighted and taunted me each day with its over mature 900 trees, woefully out of reach. I understood then that to access nature in the city would require my creativity, an observing eye, and a willingness to look deeply in unexpected places—an ever-present philosophy in the work of designer Bruno Munari, whose work and influence punctuated my trip.

In departing for these travels, funded by the Newman Exploration Travel Award, to study the legacy and work of Munari and his pedagogical forerunner Maria Montessori, I understood that I would gain a deep understanding of and appreciation for these groundbreaking figures. What I did not anticipate was the experiential knowledge I would gain—the way in which my observations, daily struggles, and emotional responses would mirror those of Munari and Montessori in the early days of their work.

Traveling to the cities and cultures they called home meant entering the crucible that cultivated their ideas and, in the process, subjecting myself to the same transformative heat. Milan, for me, as for Munari one hundred years ago, sparked feverish energy that simultaneously stimulates and drains. The epicenter of Italian design and fashion, Milan practically boils over with creative possibility but lacks the counterbalance of quiet, introspective spaces. Munari came to prominence during Italian Futurism, an artistic and social movement that embraced the speed and dynamism of this modern and industrial city and wrapped technology in an optimistic glow.

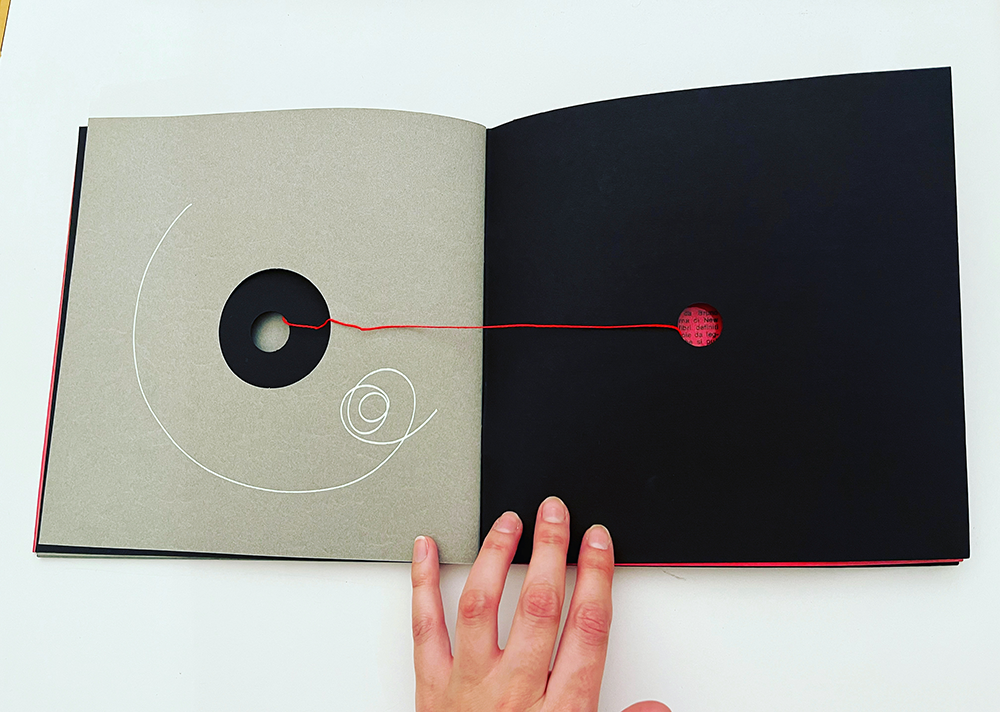

But, like me, Munari loved the natural world and his children’s picture books reveal his quest to find wonder in the small, unnoticed aspects of nature in the city—even the weather. One of his most influential books focuses on observations of Milan’s signature winter fog. Nella Nebbia di Milano (The Circus in the Mist) takes the young reader on a walk through a foggy cityscape filled with mysterious silhouettes on the way to a lively, fluorescent circus in the city center. Such work highlights his steadfast mission to find the wonder in nature even within urban settings that seem to eclipse natural elements. These shared experiences separated by a century were an unexpected gift—Milan has undoubtedly changed since Munari wrote his children’s books, but the forces that shaped his work remain accessible.

Thanks to a generous group of professors, archivists, designers, and publishing specialists who offered their time and expertise, I gained meaningful educational and professional experiences during my travels that are far too numerous to count. However, the most influential and memorable experiences of my trip offered a satisfying combination of intellectual and emotional stimulation—poignant, direct experiences with the people and places that Munari and Montessori personally touched, connecting me more deeply with their work and with my own values as a creator and a human.

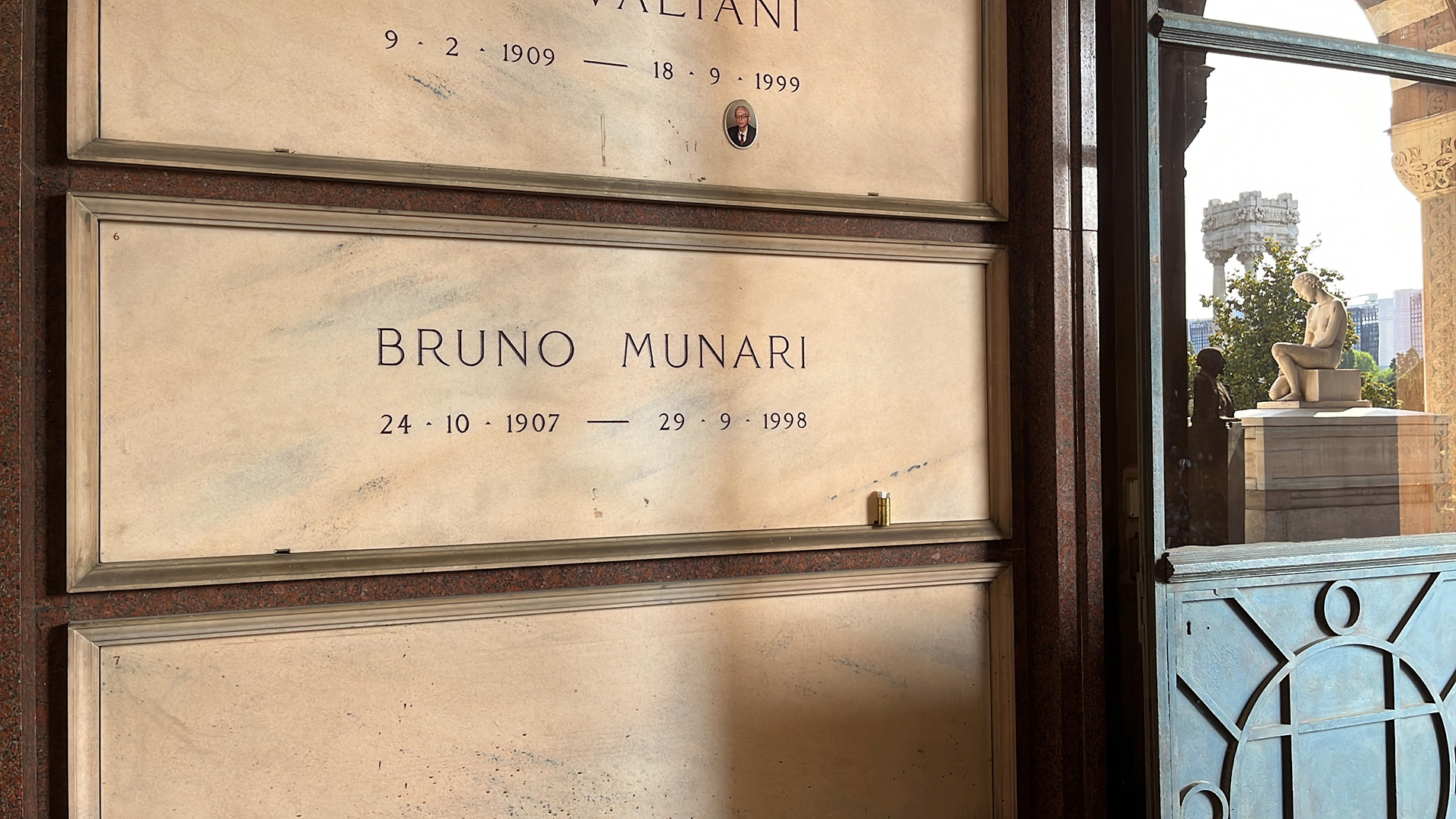

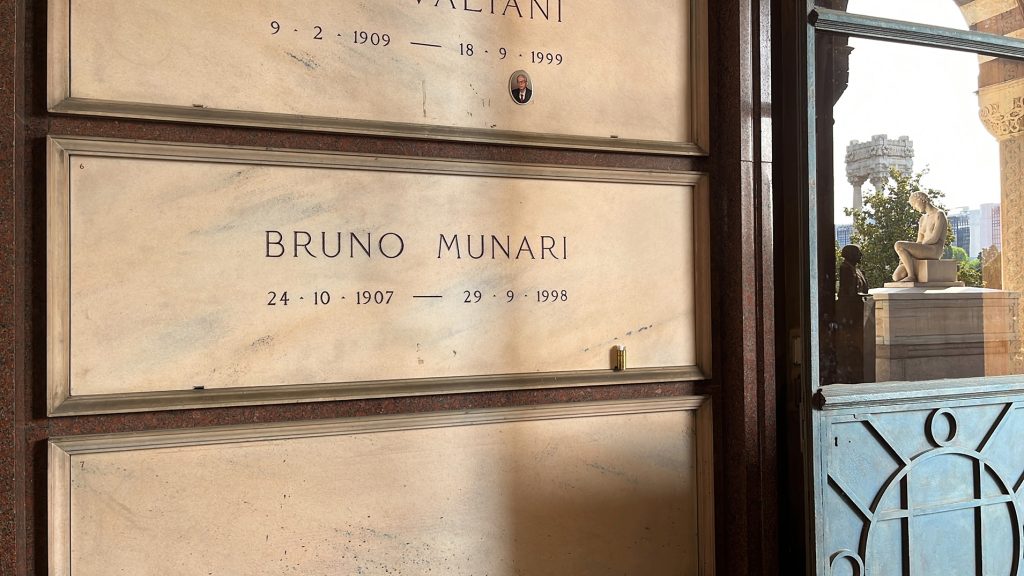

The first of these experiences came when I visited the Cimitero Monumentale, one of the largest cemeteries in Milan studded with the ornate and mournfully artistic tombs of Milan’s most well-known citizens, including Munari. I envy the way that Italians honor their beloved dead—while the living Milanese and visitors shuffled around in an endless maze of sun-blazed streets, the dead lounged peacefully under a canopy of mature evergreen trees with mossy water taps available every few feet to refill vases holding sprays of fresh flowers. Munari’s tomb sat in a prominent spot just inside a spectacular breezeway that overlooked the main gardens. Inside a small vase, I found a note written by a woman named Federica dated just a few months before, thanking Munari in beautiful, poetic Italian for giving her the gift of wonder and expressing her wish to leave some beauty behind when she departs this world, just as Munari had. Deeply moved by this epistolary connection, I left a note as well.

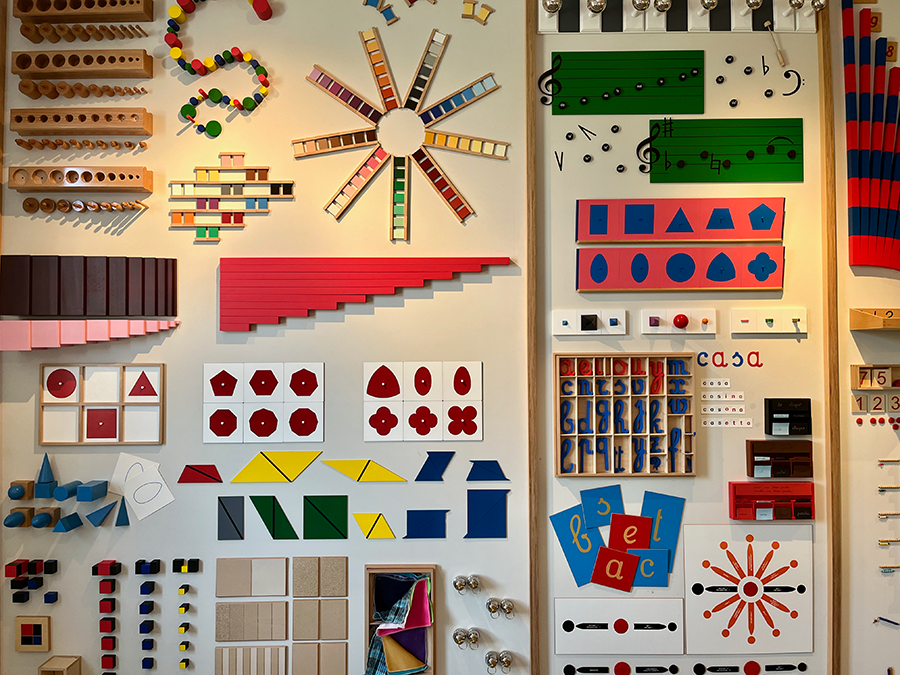

Other deeply moving experiences included my visit to Montessori’s birthplace in Chiaravalle where I met a group of designers dedicated to the promotion of Montessori’s work in the design community. While best known for her pedagogical theories, the simple, colorful, shape-based materials she developed for use in the classroom reveal a designer’s eye, keen to the intricacies of visual hierarchy, contrast, and balance. During a research trip dominated by the study of predominately male graphic designers, seeing a woman recognized for her innovative and prescient contributions to the field of design for children fueled pride.

Additionally, the Associazione Bruno Munarigraciously invited me to their educational center in the countryside outside of Milan, where I observed an educator from Munari’s original team conduct a creative workshop using the Munari Method. This experience provided me with the much-needed respite of time in nature as well as invaluable firsthand experience of Munari’s method with children. They evinced excitement and fearlessness in their creative work that exists only as a smoldering ember for most adults. They experimented with new materials without fretting about their lack of skill and reveled in the simple sensory joys of the sound of crinkled paper. Like Munari and Montessori, I believe we have much to learn from the creative processes and insights of children—their ability to integrate joy and play into their work without the burden of self-critical thought that plagues adults.

My time in Italy will impact the trajectory of my academic career at Washington University and my path as an illustrator and visual culture scholar in myriad ways. My interactions with graphic design and illustration professors and scholars at the Polytechnic University of Milan solidified my interest in pursuing an academic career in illustration. Their rewarding careers full of teaching, publication, scholarly research, and personal creative output mirror my interests precisely, and our overlapping interests will hopefully fuel future collaborations. I also established a connection with an Italian publisher I hope to pitch picture book projects to in the future. Additionally, I deepened my knowledge of archival practices in graphic design and illustration through my interactions with several museum and library curators, particularly the coordinators of the Italian Association of Visual Communication Designers. With a stronger knowledge of how to navigate archival research now both in the United States and abroad, I feel poised to enter an academic career where archival research and curation play a significant role.

On a personal level, my travels left a lasting imprint on my heart. My great grandparents immigrated from Italy, an aspect of my identity that often feels far away, insulated by the familiarity of home. But in Italy, after nearly every introduction, my companion would remark gleefully, “What an Italian last name you have.” With warmth and genuine curiosity, they inquired about my family’s origins and whether I planned to come to Italy to teach. Their kindness and interest in my life and work buoyed my spirits on days when my rigorous schedule of appointments and long walks in the oppressive heat left me feeling deflated. Traveling solo for three weeks also provided me with ample time to get better acquainted with myself. Without the protective shell of traveling as a tourist with friends or family, I quickly found that simple tasks like eating out or using an unfamiliar form of public transportation took a fair amount of bravery, but as the three weeks progressed, so did my confidence. For the last few days of my trip, I absconded to a quiet village on the shore of Lake Como to read, write, and reflect on my experiences—an exquisite respite from the heat and hustle of the big city.

All photos courtesy of Danielle Ridolfi.