My Summer with Margery

This summer, I went on a pilgrimage, spending a month following a figure who has been on my mind since I first encountered her almost ten years ago: Margery Kempe. If you aren’t familiar with Margery (which is probably most people), she was a medieval woman who dictated her life to a scribe, producing what we now call The Book of Margery Kempe, often designated the first autobiography in English. My trip this summer revolved around her. I wanted to visit the places where she had been, but I also wanted to recreate the experience of pilgrimage that she describes in her text. To that end, I visited several places that Margery never went to but that represented destinations—literary, emotional, or spiritual—for me. This mixture of tourism, research, and pilgrimage allowed for an amazing experience that revealed many things about myself and my work, and it would not have been possible without the Newman Exploration Travel Fund.

Upon arrival in the UK, walking out of Heathrow was like stepping into a portal. London had come to represent so much of my literary and historical imagination, and I was finally there! But I wasn’t in London for an hour before boarding a train bound for Norwich, a small city in Norfolk and home to one of Margery’s most famous contemporaries, Julian. Julian—another medieval holy woman whom Margery visited in her lifetime—is famous for the mystical visions she received while enclosed in an anchorhold. Although I received no visions of my own, I visited that room and the rest of the church and found myself overwhelmed by her presence there. This year is the 650th anniversary of 1373, the year that Margery was born and the year that Julian received her visions, so many folks that I met were excited to hear about my interest in this pair.

From Norwich, I briefly visited Ely’s gargantuan cathedral before continuing onto Walsingham, a tiny village near the north of Norfolk and home to one of medieval Europe’s most visited religious shrines. While the original shrine and the priory that housed it are no longer intact, their ruins remain, and coupled with the dreary Norfolk weather, they made for a hauntingly gorgeous stroll. Walsingham remains an active pilgrimage destination today. I stayed in the lodging that is maintained by the church there and met many other pilgrims over shared meals and the walk from the village to the site of the shrine (The Holy Mile).

A scenic bus ride brought me finally to King’s Lynn, Margery’s hometown. Now a mid-sized town, King’s Lynn was once a bustling mercantile port city. Not much of Margery’s personal existence is curated in King’s Lynn: we don’t know the location of her home, nor do we have many artifacts or locations of her life in their medieval form. With a little digging, however, I was able to visit some sites that brought me into close contact with her, even 600 years later. One such place was Mintlyn, a small village outside of King’s Lynn. Margery mentions this village in her Book because she visited the church of St. Michael there with two priests who wanted to test the authenticity of her piety by removing her from crowds. The church still stands, but not as a preserved historical site. Rather, after a bus ride and 45 minutes of walking alongside the shoulder of the highway, navigating along unmarked roads with a set of coordinates and the GPS on my phone, I found the decaying remnants of this church in the middle of a field. Parts of four walls remain on the roofless structure, but large weeds had sprung up through the middle, an overgrown protrusion through the church’s nave. Walking a mile north, I found the ruins of St. James, another medieval church that Margery almost certainly would have visited. Both buildings erupt from the ground as if indiscriminately scattered on the modern landscape, just a few minutes walk to a large hospital complex and a six-lane highway, monuments to this place’s rich history lurking just out of the familiar view of the everyday.

From here, my trip took a slightly different turn. I still had some Margery-themed stops remaining in England—the Lincoln Cathedral and Bishop’s Palace, the York Minster, and London, of course, which could have occupied the entire five weeks of my trip itself—but I had also planned stops at more personal destinations along the way. First up was Leeds, where I saw one of my favorite British bands of all time, Bombay Bicycle Club, play a show in an old warehouse turned hip venue. I had tickets to see them in St. Louis in March 2020, so it felt right for those Covid-thwarted plans to return to me on an even better stage, in England (!), with this setlist and these people. After my night in Leeds, I took a quick train to York before renting a car to hit some remote spots inaccessible via public transit.

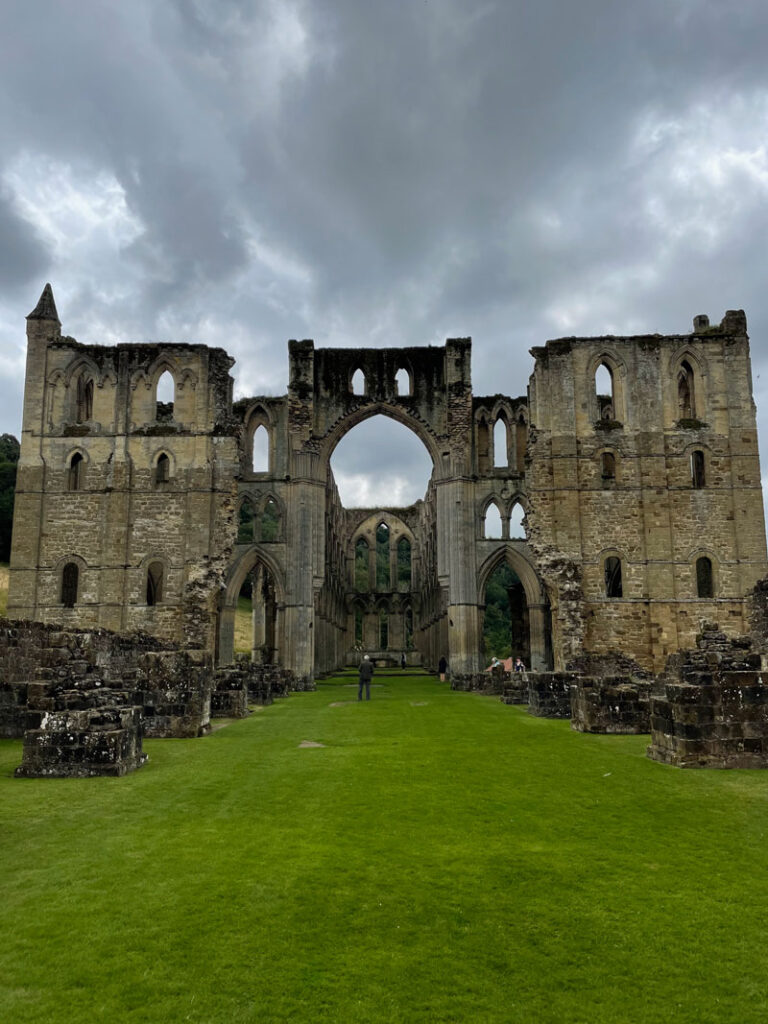

Driving in England was at once terrifying and exhilarating. My first stop was the ruins of Rievaulx Abbey that tower over the flat valley of the North York Moors landscape. Nothing could have prepared me for just how massive these stones were, and I quickly understood why this was such a popular destination. My second stop was Mount Grace Priory, another set of ruins an hour’s drive from Rievaulx. Margery never visited, but the only surviving manuscript copy of her Book was housed there and miraculously survived the destruction of the religious houses under Henry VIII, so it was a necessary stop on my pilgrimage. Seeing the ruins of the monks’ cells, as well as a reconstruction of what they might have looked like, I could imagine one of the brothers reading the Book in the precious little sunlight that entered through his garden windows. From Mount Grace, I drove up the coast to the Holy Island of Lindisfarne, one of England’s oldest pilgrim destinations. While called an island, it is a peninsula that becomes an island when the tides flood the causeway at certain times during the day, meaning that you can only enter and exit the island through windows. At Lindisfarne, I explored the abbey ruins and the castle, both of which afforded great views of the coast. After waiting for the tide to subside, I drove to Edinburgh, dropped off the car, and then caught a train back to London where my partner would be arriving the next morning.

As I mentioned earlier, London deserves its own trip. There are many Londons, and the medieval one, while hidden under the palimpsest of the others, remains in flashes. I found vestiges of that London, the London of Chaucer and Margery, as I meandered Southwark and Lambeth. Thankfully, there were also vestiges of that London curated and preserved in the British Museum and Library, which brought us face-to-face with some incredible cultural artifacts, such as the Sutton Hoo dig site and the Rosetta Stone.

Our journey in Italy followed a similar trajectory to England, with a mixture of Margery and non-Margery sites that, together, approximated a sense of the pilgrimages that she would have taken in her lifetime. Margery took us to Venice, Bologna’s Santo Stefano with its life-sized reproduction of Jerusalem’s Holy Sepulcher, Assisi’s mountainous San Francesco, and Rome’s assortment of famous churches, including Saint John Lateran, where Margery weds Christ in her Book. But our interests took us to Ravenna, a wonderland of mosaics, Florence, a medievalist’s dream, and Foligno, the home of Angela, another medieval woman whose life resembles Margery’s although they never met. In visiting both kinds of places, I felt close to Margery, not only because she had gone there before me, but also because I resembled her more each day: a travel-weary English speaker who felt simultaneously at home and out of place in a land where I didn’t quite speak the language or know the customs, being unfamiliar in an unfamiliar place.

Perhaps the most personally and academically enriching aspect of the trip was this experience of uncertainty that accompanied me at points throughout my five weeks abroad. In her Book, Margery describes how pilgrimage often opened her up to the contingencies of life, both negative—running out of money, not speaking the language, having her belongings stolen, annoying her companions so much that they abandoned her, being tried for heresy—and positive—meeting people on the road who provided support, experiencing smaller places along the way that she hadn’t planned for, being surprised by the generosity of strangers. My trip was no different.

While I was (luckily) never tried for heresy, I had my fair share of mishaps: last-minute flight changes in Chicago, the multiple times that I missed a bus in Walsingham that ran only once an hour, getting stranded on Holy Island after misreading the tide table, a hefty tourist fine after forgetting to validate a bus ticket in Florence, the walk from the Roma Termini to an apartment that our host said would be “easy” and “mostly downhill” but ended up being neither. But there were also moments of true wonder that arrived out of nowhere and that I did my best to receive as gifts, such as the host of my Airbnb in Norwich, chosen for its cheap nightly rate, who turned out to be a writer and who invited me to a writers night at Dragon Hall, a medieval building (not open to the public) that houses the National Centre for Writing. Norwich held many such gifts, like my hosts’ lovely neighbors who invited me to their monthly get-together to drink wine and play music, or the women at the Julian shrine who conversed with me for hours and lent me books with no question of whether I would return them. I could tell many more stories—the pub landlord in Dulwich who explained the importance of brown sauce, the horde of cats that greeted us outside our apartment in Assisi, the Vespers that I accidentally heard sung in Ely, or our sweet host in Venice who picked us up from the airport and encouraged my broken Italian through his own broken English—but they would never do justice to my experience this summer. This experience would not have happened without leaving the comfort of my routines and opening myself up to the uncertainties of travel, and I owe that privilege to the NEXT Award.