James Dickey and the Apollo Program

Written by Irina Teveleva

On the fiftieth anniversary of the July 20, 1969, Apollo 11 moon landing, we are showcasing materials in the Modern Literature Collection related to space exploration.

The James Dickey Papers include correspondence, manuscript drafts, editorial matter, and more from the American writer and poet James Dickey (1923–1997). A long-time poet-in-residence at the University of South Carolina and a former poetry consultant for the Library of Congress (now known as Poet Laureate), Dickey wrote more than 17 books of poems and 12 books of prose. His most famous works include the National Book Award-winning poetry collection Buckdancer’s Choice and the novel and screenplay Deliverance.

The biography James Dickey: The World as a Lie by Henry Hart details how James Dickey covered the Apollo 7 rocket launch, the first manned Apollo mission, on assignment for Life magazine; according to Philip Kunhardt, an assistant managing editor at Life, “His assignment was to turn his considerable poetic talents to our exploration of space.” In a trip organized by Life, Dickey flew to Florida in 1968. He dined with the Apollo 7 astronauts in crew quarters and watched the launch of Apollo 7—the first manned Apollo mission—at Cape Kennedy.

On January 10, 1969, following the Apollo 8 mission, the first manned mission to orbit the moon and return, Dickey’s poem “For the First Manned Moon Orbit” appeared in Life Magazine. It was published in a 10-page spread alongside photos of the astronauts, the earth as seen from outer space, stunning moonscapes, and other cosmic sights. The page with the poem can be viewed through Life Magazine’s free public archive here.

That summer, Dickey returned to Florida to watch the launch of the Apollo 11 moonshot. Life magazine ran Dickey’s poem “The Moon Ground,” first in the July 4 issue, preceding photos of the astronauts, and later in an August 11 issue dedicated to Apollo 11’s return to earth right next to a photograph of Armstrong, Collins, and Ardrin. Dickey also read “The Moon Ground” on ABC television on July 20, 1969, the day the astronauts landed on the moon.

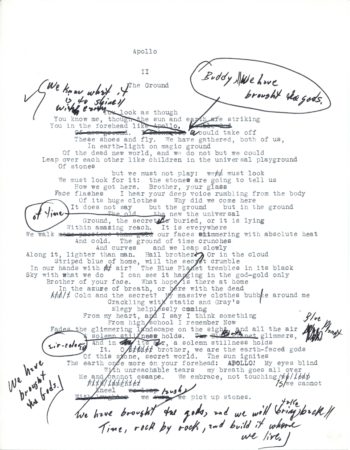

The two poems were published together in the poetry collection The Eye-Beaters, Blood, Victory, Madness, Buckhead, and Mercy (1970) as two parts of the long poem “Apollo.” They describe a visionary, metaphysical experience of outer space in a formally experimental way: “Apollo” is center-aligned, evoking weightlessness and the trail of a spaceship leaving the earth. In addition, according to Henry Hart, when the poem was reprinted in The Whole Motion: Collected Poems 1945–1992, the phrases “it is something /Else: nothing is something / Something I am trying / To say O God” were followed by “two half pages and one full page of total blackness.” The black space, Hart writes, “corresponds to the communications blackout the astronauts experienced while flying around the dark side of the moon.”

This was the end of Dickey’s topical poems on the Apollo program, but the experience stayed with him for a long time. In a remembrance for Poetry magazine, the poet James Mehigan describes writing a fan letter to Dickey in the summer of 1996—the last year of the poet’s life—and receiving a phone call from the poet in response:

“‘Mr. Mehigan?’ the caller asked. […]

‘Hello?!’ I said.

‘Hello,’ said the caller, calm. […]

‘Mr. Mehigan, this is Apollo.’

I kept quiet while I decided whether or not to hang up.

‘Uncle George?’ I asked.

‘No, Apollo,’ corrected the caller, gently. I now discerned he was from the southeast, past seventy, and might really be my mother’s uncle George, who had a funny sense of humor. But he pronounced my name ‘Me-again.’ Then I remembered giving out my contact information at a poetry reading the previous weekend.

‘Is this about the reading on Thirteenth Street?’ I asked.

‘No,” said the voice, still calm but faintly disappointed. “Mr. Mehigan, this — this is Apollo … God of Poetry!’

I stood for a long five seconds as the caller softly repeated himself like a game-show host offering a hint. I had no idea who it was but wasn’t going to hang up now.’”

More drafts of the “Apollo” poem are available through the Modern Literature Collection: The First 50 Years website.