Investigating Democracy in Five European Countries

I’m grateful to the Newman Exploration Travel Fund (NEXT) program for the funding that enabled me to spend three weeks of my summer exploring five European countries with unique approaches to democratic governance. As an incoming second-year student with an interest in political science, I’m curious about the many countries that outperform the US on democracy metrics and what they can teach us. During my trip through the UK, Belgium, Estonia, Austria, and Switzerland, I did my best to observe how each country’s system of government produces both benefits and challenges. I saw the urgency of including a diversity of linguistic and ethnic communities in political systems, took note of the success of non-professional politicians, and experienced firsthand the importance of collective belief in an age of democratic anxiety.

United Kingdom

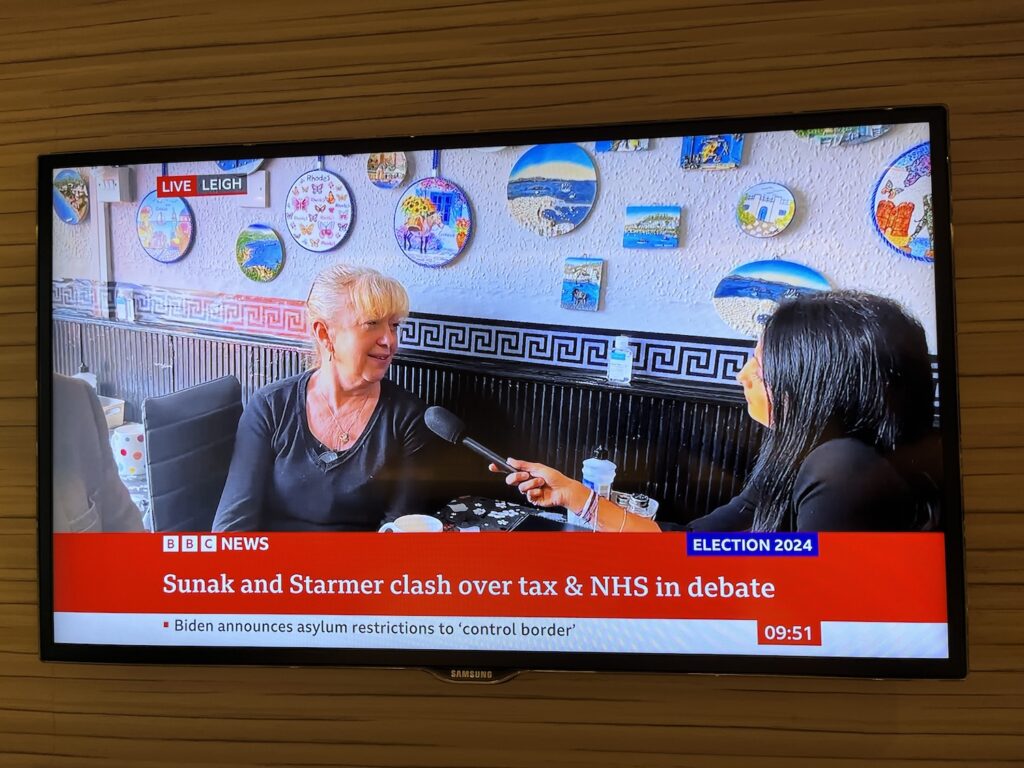

My first stop was the UK, ranked 18th in the world by the V-Dem Democracy Index. I touched down in London shortly after the general election was called, too late to sit in on sessions of Parliament as I had hoped but just in time to watch Rishi Sunak and Keir Starmer compete for the position of prime minister. I gasped with excitement the first time I saw a political ad on the side of a bus, although the moment was too brief for me to capture it. I bought newspapers from street stands and watched on television as the two candidates debated each other. I spent the afternoon with a family friend and spoke with students and faculty outside the London School of Economics. I was especially eager to understand the perception of referendums in the UK and whether or not the controversial outcome of the Brexit referendum had affected support for referendums as a principle.

The UK’s 2016 departure from the European Union did not live up to its promises of increased public funds, freedom from EU regulations, and a decrease in net migration. As the prime ministerial campaigns rolled out, though, I was surprised never to hear Brexit mentioned.

During the previous election cycle, the Conservatives ran on the platform “Get Brexit Done,” but there was no reference to the Brexit deal in the debate between Starmer and Sunak. One LSE professor I stopped on the street believed that “Britain has moved on.” The family friend that I spoke with thought differently, remarking “Brexit is the elephant in the room.”

Regardless of how they split on the Brexit issue, the Londoners I questioned supported referendums in theory. Our family friend suggested that referendums should require a higher threshold to pass, citing the narrow 3.78% margin of the 2016 vote. It may be useful to consider, however, that my anecdotal experience countered the way Brexit is presented as a cautionary tale in academic discussion. At least among the handful of people I talked to, the principle of referendums still held tremendous value, with the caveat that democracy must be more than a tyranny of the majority; it must also protect the interests of minority groups and opinions.

Belgium

Within a few days, I took the Eurostar train to Brussels, one of the headquarters of the European Union. Smurfs were everywhere in the city—the little blue people were invented in Belgium—along with designs from Belgian comic books. The warm air that blew in through my hotel window was saturated with the smell of waffles. Below, the streets were crammed with musicians, chocolate shops, and tourists eating hot fries out of paper cones.

In the morning, I video-called a friend’s connection, the French-speaking Madame Françoise. She spoke highly of Belgium’s compulsory voting laws. Madame Françoise argued that politicians have to try to explain to the whole population what they have to offer, instead of catering to a particular niche. And because attendance at voting stations is obligatory, most people go who would otherwise not attend. In fact, Françoise’s registration with the Green Party placed her on a list of names that meant she could be selected as the Green Party’s candidate for election in local races.

When her turn came around the first time, she declined. Later, when her name came up again, she reconsidered. Her interest in politics and sense of civic duty led her to run, and now she enjoys being a local councilor in her small Belgian town. As a member of a small party at the negotiating table, she said she must “be courageous.” I appreciated Madame Françoise’s story of success as a non-professional politician.

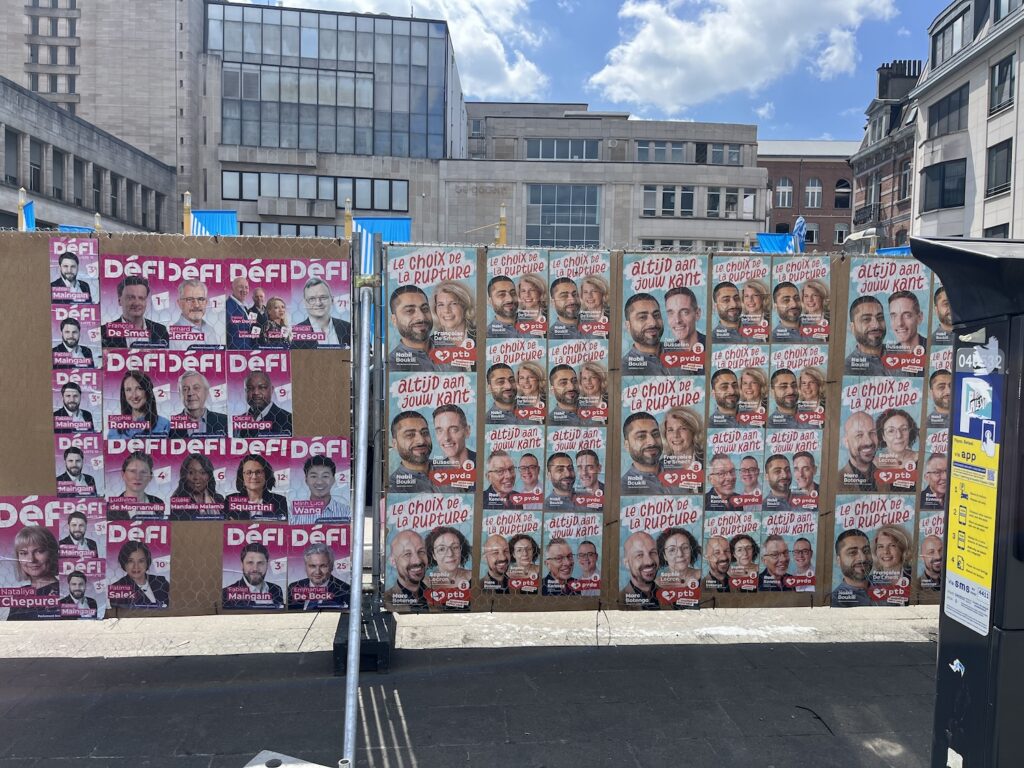

And yet, by no means does Belgium have all the answers. In Belgium, the election on June 9 was widely feared to be “the beginning of the end,” as phrased by my Belgian tour guide. Belgium is divided by language. To the north lies the Flemish-speaking (Dutch) Flanders and to the south is the French-speaking Wallonia. A few pockets in Wallonia are German-speaking. While Flemish students usually learn both French and Dutch, it is common for French school students to receive only a monolingual education. Belgium’s capital, Brussels, is situated in the northern half and yet French is the lingua franca.

The language issue was at the heart of the anxieties around the summer election. A Flemish nationalist political party titled Vlaams Belang (“Flemish Interest”) was expected to score major victories in the polls. The conservative group is hostile to the EU and considered to be a far-right extremist organization, such that no other parties will negotiate with Vlaams Belang, a policy called le cordon sanitaire. On June 9, Vlaams Belang fell short of projections, but the question remains of whether or not the Belgian government will make Flemish voters feel heard. My Belgian tour guide lifted his hands and mimed two pieces coming apart.

Estonia

My third destination, Estonia, faced a similar struggle following its recent independence, having different language communities with potentially different political goals. Tallinn was one of my shortest stays and easily one of my favorites. Beautiful medieval architecture crisscrosses the Old Town, and when I arrived by a red eye, the orange roofs still stood out somehow in the bluish one a.m. light. Almost as soon as I got in a car to leave the airport, Estonia’s uncertain future came up in discussion. “We are safe now,” my kindly driver said. “But in five years… I don’t know.”

The Estonians I met were acutely aware they lived in a small country with small coffers, in a capital city two hundred and ten kilometers from the Russian border, in a place that could cease to exist. I learned that the two kilometers of medieval wall and twenty-six impressive, intact defense towers that are emblematic of the Old Town were once slated to be torn down post-independence, but remained because the government could not come up with the money. For decades, visitors to Tallinn could only stay in one hotel because KGB surveillance agents were posted on its top floor. I saw a few Soviet-era brutalist buildings. Tourists from cruise ships wandered in the main plaza; in the evenings, quietness crowded in. A few blocks away from former KGB prison cells, signs expressing support for Ukraine were tied to metal barricades. A single military vehicle hummed past a marzipan shop.

“If you’re wondering if there’s tension between the Russian and Estonian communities,” said my tour guide, a young Estonian with two Russian parents, “[ethnic] Russians and [ethnic] Estonians can get married and it’s very normal.” But when asked about the Russo-Ukrainian War, denounced strongly by the Estonian government, the guide observed that he was not in support but “people will not tell you what they really think,” hinting, perhaps, at differing opinions in the ethnically Russian community.

Even in the fifth most democratic country, per V-Dem Indices, the government does not always endear itself. My tour guide did not talk about the Estonian parliament with particular love. In Freedom Square, he pointed out a tall, columned monument modeled after the Estonian Cross of Liberty, and explained it costs the government thousands of euros per month just to clean the glass.

Our guide’s humorous self-deprecation did not mean, however, that there was a shortage of national feeling. During my car ride back to the airport, I tried to start a conversation about the upcoming Midsummer celebration, which I had been told was the biggest holiday in Estonia. My new driver was skeptical. “I don’t think it’s that big of a deal,” he said. “What holiday is a big deal?” I asked. He considered. “Our Independence Day,” he told me with a note of pride. “Everyone gathers to sing.”

Austria and Switzerland

Over the remaining dozen days of my trip, I moved around Switzerland and Austria on planes, trains, and even an Austrian sleeper train called a Nightjet. Austria, to its credit, takes steps to encourage citizen input. The Austrian Parliament in Vienna, which just reopened this year after being renovated, is a public-centric space. A brightly-lit central hallway leads visitors to an information desk, eighty hours of content on interactive displays, and an accessible research library. I did not sit in on a session, but I toured the galleries.

One chamber of Austria’s legislature, the Federal Council, is composed of non-professional politicians appointed by proportional representation. Granted, the Federal Council is not very powerful and has only vetoed one law in its history, but it still provides an opportunity for ordinary people to influence the crafting of policy in a hands-on way. Plus, the government sometimes convenes local wisdom councils, which are a kind of small focus group for citizens to hear each other out and share their opinions on policy.

In Linz, Austria, I visited a distant relative (my second cousin’s mother-in-law), who expressed to me her concerns about increasing nationalist anti-immigration rhetoric in Austria. A young child in Germany during World War II, she was disturbed by some politicians’ endorsement of racist messaging. As in many other places, the delicate balance between majority power and minority protection is playing out in Austria.

I beelined to Bern to watch a few days of the Swiss Parliament in session. As someone who speaks no German, Italian, or French, I relied on my Spanish to decipher the rapid-fire speeches and votes through an in-house Italian translation headset, leaning out of my seat with effortful focus next to a security guard who may have been a little bemused.

Overall, I was impressed by the efficiency of the proceedings. In the National Council, four to six proposals could be discussed and voted on within an hour. Once, a few rows in front of me in the gallery, a small group of elderly people unfurled banners and chanted in protest in French. They were quickly broken up. Most politicians in the chambers are semi-professional and have other jobs since sessions last a total of twelve weeks per year. Detailed conflict of interest disclosures are no more than a few clicks away on the official Swiss government website. Referendums are held regularly to decide important questions, and any law that citizens object to with a petition can be challenged in a referendum.

I asked my Bernese tour guide about all these referendums, and he shrugged, saying something along the lines of “Oh ja, of course.” (He became most animated when pointing out members of the legislature or former politicians walking down the street, impressing upon us that they required no bodyguards.) In short, many of the policies being tested out in other highly democratic places had come together successfully in Switzerland. I can understand why, in the V-Dem Index, it is ranked number one.

In addition to seeing democracy in action around the world, one of the most valuable lessons of the trip was a more personal one: how to talk to strangers. In London, I was very nervous to approach random students (and, accidentally, one professor) and ask them for their time to talk about politics. I felt bad for bothering students who were chatting with friends or on their way somewhere, but most people were very kind. When students set their boundaries (“no thank you,” “just one question”), I understood and moved on. My embarrassment was slightly relieved by the fact that I would be leaving the country immediately.

Separately, on a train out of Switzerland, I enjoyed a long conversation with a retired couple sitting across from me. I had just had food poisoning the day before and I was steeling myself for an eight-hour train journey. I will admit that I intentionally tried to appear extra sick to dissuade them from sitting near me, including by holding a paper bag up to my face and clutching my forehead. And still, they sat down. They were very friendly people with impeccable English. I learned about their multi-week bike ride, the story of how a couple they knew had first fallen in love, the fourteen-month paycheck system in Austria, their favorite parts of Innsbruck, and their relative cluelessness about The Sound of Music, the background track to my childhood. I broached the subject of studying politics in school, and they chatted with me about their son living in Switzerland, which they thought had a much more democratic structure. Their son was moving into a newly built housing unit and all the tenants had to come to a consensus about the shade of the exterior paint; it was the kind of information I would never know from parsing apart Italian in the Swiss parliament.

I also got to spend time with my mom. She accompanied me on my journey, mainly for safety reasons. Initially, I was concerned that her decision to join me would complicate the solo traveling experience I had planned, but I was very lucky to have her company. When I wrote my NEXT program application at night in my dorm room, dreaming up big questions about direct democracy electoral strategies, and citizen participation, I expected, if selected, that I would spend three weeks of my summer largely alone. I had no idea that the most enriching part of my trip would be sharing it with other people. If you’re still reading, thank you for giving me the opportunity to share it with you.