Illustrated Poetry in the Henrietta Hochschild Collection of Children’s Books

Poetry is a celebration of language and sound. Originating as an oral tradition, poems have moved audiences with their rhyme, meter, and wordplay for centuries (Styles, 2020). Poets wield words to paint evocative scenes rendering pictures somewhat superfluous. Nevertheless, many volumes of poetry include beautiful illustrations. The Henrietta Hochschild Collection of Children’s Books contains many illustrated volumes of poetry for children and exploring them reveals the roles illustration can play in poetry. While language is evocative, it can also be ambiguous and abstract, and therefore challenging for young audiences (Elster, 2000). In prose-based picture books, the text often serves as a guide to help children interpret or further expand upon the action in the pictures (Nodelman, 1988). For instance, a picture might show two children walking down a path together while the text clarifies the reason for their journey. However, illustrated poetry reverses these roles; pictures serve to fill in a poem’s gaps and to bring the meaning of words, emotions, and worlds into sharper focus.

Images as Comprehension Aids

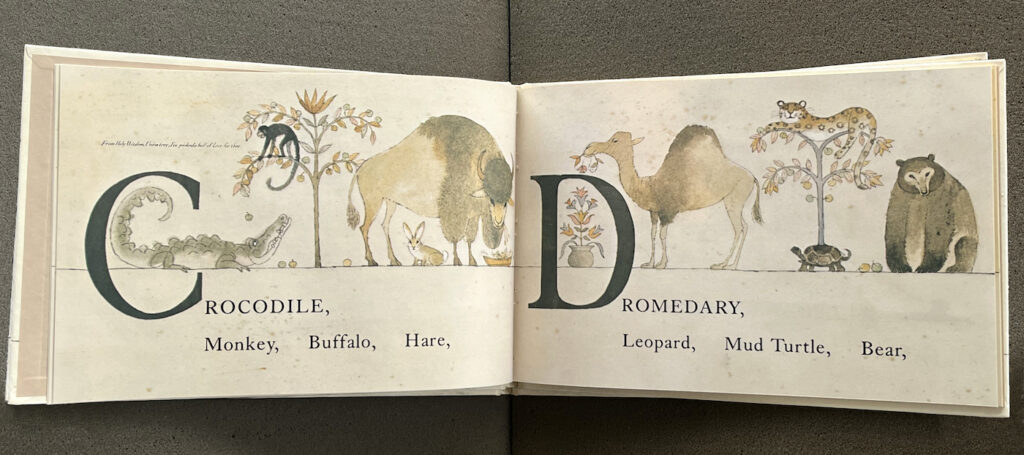

Illustrations in poetry can offer helpful visuals for words outside the realm of a child’s vernacular. In nursery rhymes, these illustrations may be simple explanatory pictures of animals or objects to aid in vocabulary acquisition. A Peaceable Kingdom: The Shaker Abecedarius, written and illustrated by Alice and Martin Provensen in 1978, provides an excellent example of this type of explanatory picture. The verses list names of animals beginning with each letter of the alphabet, accompanied by large drawings of both the letterforms and animals. The charming combination of rhymes and pictures makes learning letters fun.

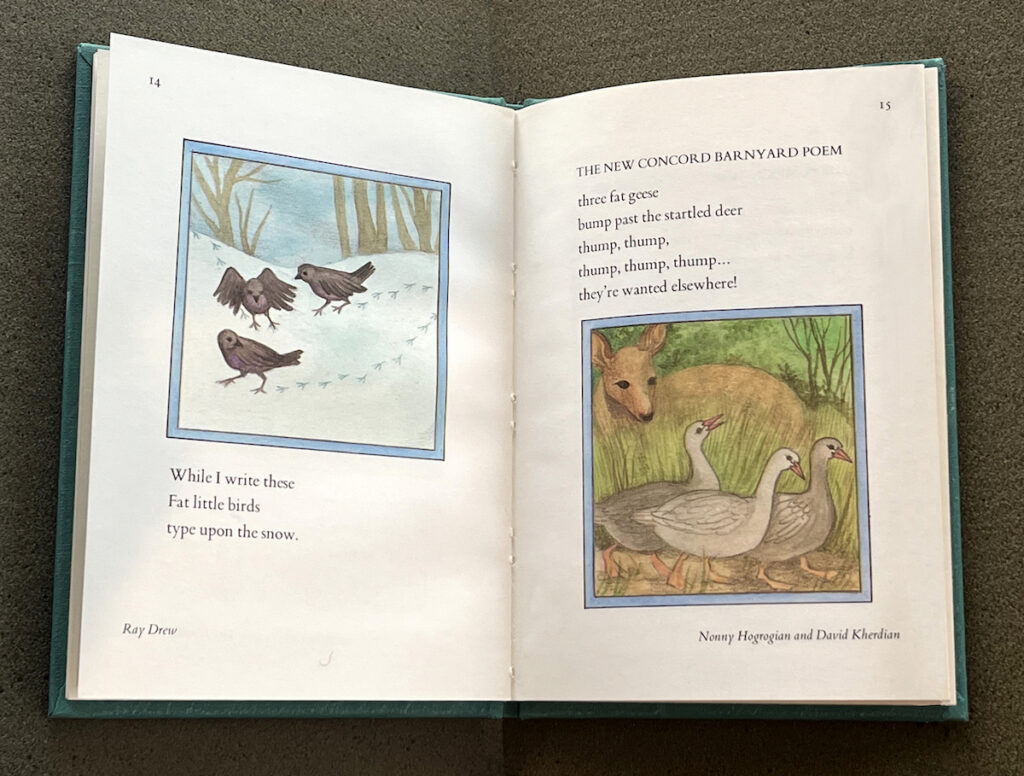

In more complex poetry, illustrations can offer pictorial representations of metaphors that children may not understand with words alone. The Dog Writes on the Window with His Nose, a collection of poetry published in 1978 and illustrated by Nonny Hogrogian, features several challenging lines, like calling a bird’s footprints “type upon the snow” or describing a cloudy moon as having “a cat’s mustache.” Pictures offer the child suggestions for interpretation, modeling methods for deciphering metaphors in the process.

Images as Mirrors for Language

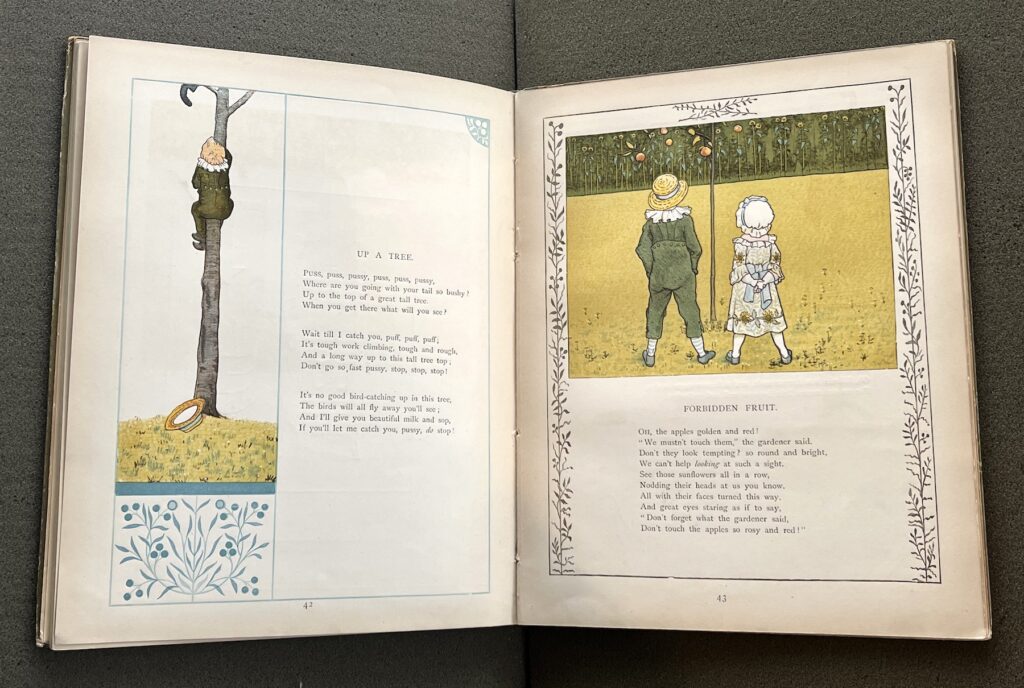

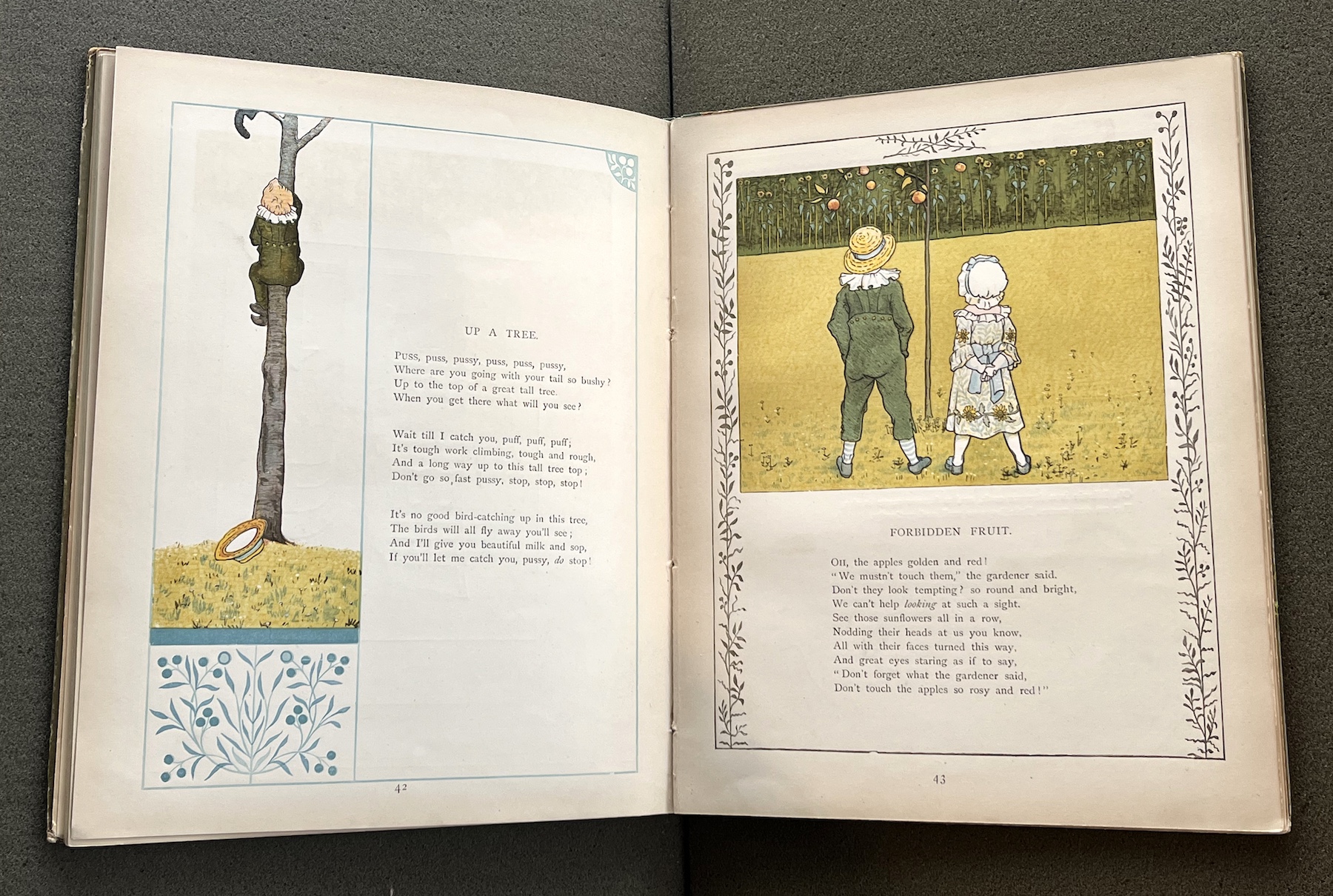

Pictures can also help to highlight the beauty of a poem’s language. Poetry is a celebration of words—their rhyme, repetition, and melodic qualities. But many children are still learning how to appreciate these formal qualities. Illustrations can not only entice children to read poetry in the first place, but they can also enhance a child’s experience of language. Afternoon Tea: Rhymes for Children by J.G. Sowerby and H.H. Emmerson from the early 1800s demonstrates this trend well. Its decorative elements, like ornate borders and page flourishes, mirror the rhythm and repetition of the poems themselves. Even the central illustrations often contain repeating patterns that give the eye a rhythm to follow while listening to the words.

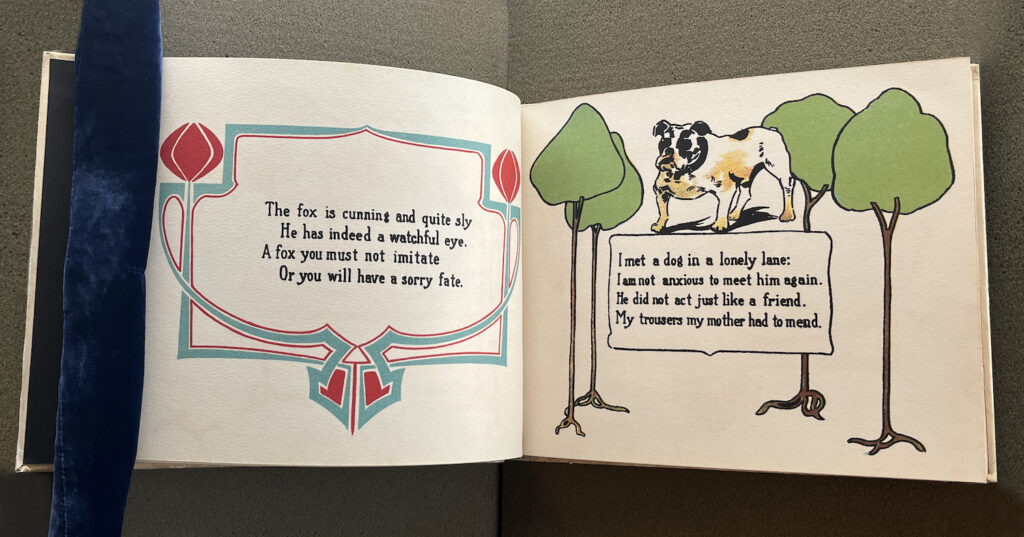

Despite being published almost 100 years later in 1909, Goosie-Gander Rhymes by Gertrude Lowenheim uses similar methods. The illustrations, composed of icon-like images and colorful, decorative borders, mirror the volume’s narrative of exuberant fun. These decorative elements demonstrate that poems aren’t just about content, but about the pleasure of form.

Images as Invitations to Other Worlds

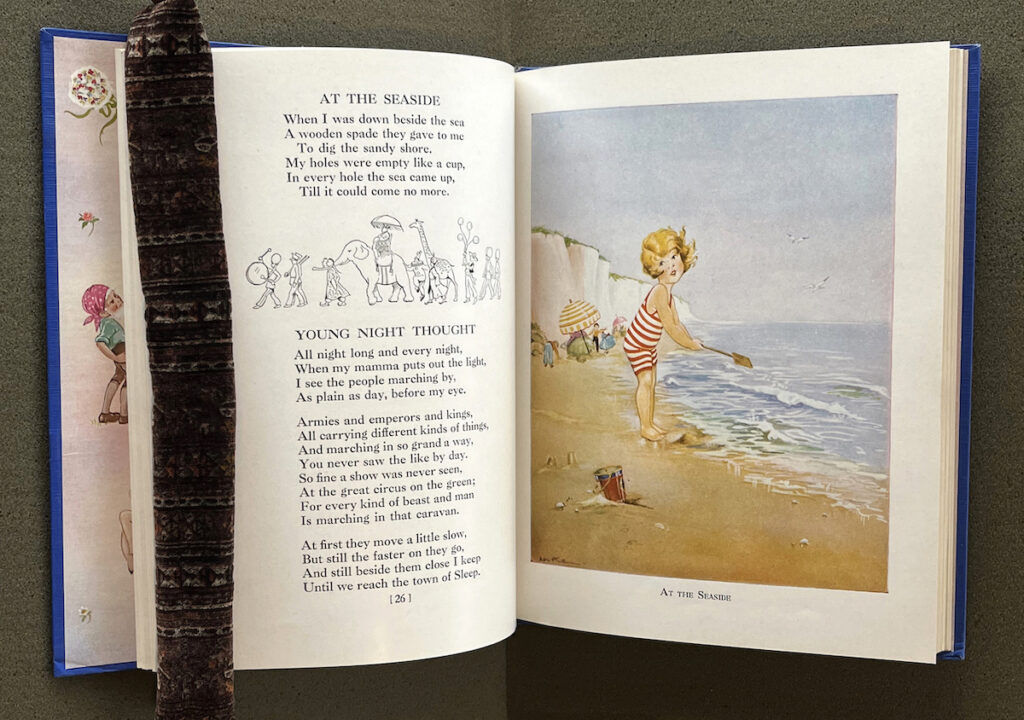

Illustrations can also serve as an invitation into the world of a poem. More than in perhaps any other type of writing, poetry depicts powerful new ways of experiencing and interpreting our world and our role within it (Elster, 2000). Detailed illustrations invite readers to occupy the poet’s perspectives—to fully inhabit them. One beautiful example is the 1929 edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses illustrated by Eulalie. The illustrations depict idyllic scenes of playtime in the garden or at the seaside—a world where childhood never ends. While childhood is fleeting, as Stevenson often points out in his poems, readers of any age can visit his nostalgic poetic worlds as long as they like, simply by looking at the pictures.

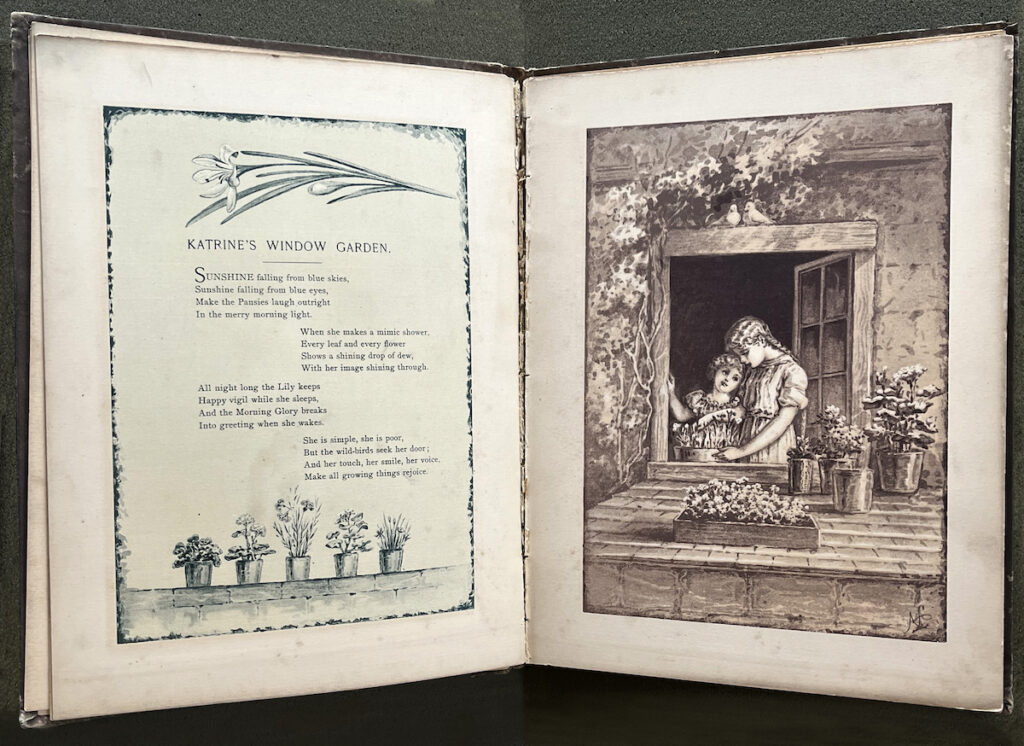

A similar treatment can be found in Mary A. Leathbury’s From Meadow Sweet to Mistletoe, published in 1886. In a somber introduction, Leathbury dedicates the poems to a young boy seeking companionship through books after his brother’s death. With this collection of poems and pictures, she seeks to create a fantasy world filled with beauty and happiness —a world very different from the unpredictable and sometimes tragic world that her readers inhabit. The sweet, sentimental illustrations serve as the gateway to this idyllic place where readers can’t help but want to linger, particularly during times of sadness or hardship in their own lives.

While poetry can be challenging, requiring active participation and interpretation from the child or the adult reading to them, it can also provide a beautiful way to explore complex emotions and metaphors and engage with language in a way that feels like play. For many children and even adults, illustrations can open the door to a better understanding of the world and increase self-reflection. The illustrated volumes of poetry in the Henrietta Hochschild Collection of Children’s Books are an excellent resource for students and scholars of poetry and literature or for early childhood educators interested in engaging their students with poetry.

Danielle Ridolfi is a master’s student in the Illustration and Visual Culture Program at Washington University. For more information about volumes of illustrated poetry in The Henrietta Hochschild Collection of Children’s Books, please contact the curator of rare books, Cassie Brand.

Sources Cited

Nodelman, Perry. “The Relationship of Pictures and Words.” In Words About Pictures: The Narrative Art of Children’s Picture Books, 193-221. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 1988.

Styles, Morag. “Go Deeper: Poetry for Children.” The British Library. The British Library, February 21, 2020.

Elster, Charles A. “Entering and Opening the World of a Poem,” Language Arts 78, no. 1 (2000): 71-77.