How Will the Free, Zero Embargo Memo Impact the Humanities and Social Sciences?

The most recent White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) memorandum, Ensuring Free Immediate & Equitable Access to Federally Funded Research (Nelson, 2022) requires federal grant agencies to ensure that researchers who receive federal funds deposit their peer-reviewed scholarly publications in agency-designated public access repositories without any embargo or delay after publication. Prior to this, the 2013 memorandum allowed for up to twelve months’ delay in providing public access to research funded by certain federal grant agencies. While the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) has yet to provide specific details in response to the recent memorandum (although the public access policy does not need to be updated until December 31, 2024), it is relevant to humanities and social science researchers, as the memo cites peer-reviewed book chapters, editorials, and conference proceedings as being subject to its provisions.

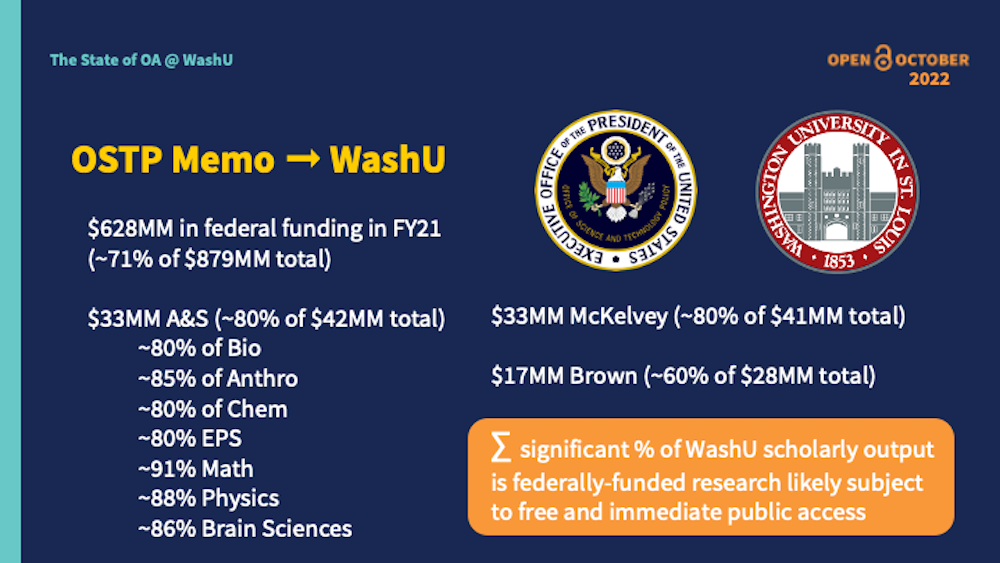

This post is not intended to be a general introduction to the 2022 White House Office of Science and Technology Policy memorandum. There’s a significant amount of federally funded research at WashU for STEM and other disciplines that are subject to open access. The present article focuses on the humanities and social sciences because these areas were the focus at the 2022 Indiana University-Bloomington’s Open Access Symposium, but there is a lot of commentary on the potential impact of the memo for different subject areas. The University Libraries would be open to contributing future posts that focus on other subject areas in the near future.

Research has been slow to shift toward open access, and the COVID-19 pandemic showed us open research benefits the greater public. Government guidance, such as the recent memo, can and will push society and open information to where it needs to be, but it is not without risk. Europe’s Plan S, perhaps due to its specificity, such as no publishing in hybrid journals (which contain a mix of open and paywalled articles), had issues with adoption. Is the recent memo’s vagueness a strength (allowing for compliance flexibility) or a weakness (allowing for inequitable means of open access)?

While the memo addresses the humanities and social sciences, it unsurprisingly pays more attention to research publications in the sciences. This has led many to believe that humanities publishing will be far less impacted, which may be true, but the memo will still affect the humanities and social sciences in the following ways:

- How to adopt data sharing policies with little consensus of what constitutes as data;

- How funding for research and research dissemination may change, given the memo’s agnosticism to funding models (and lack of clarity on publication versions and licensing);

- Whether new funding models and changes in research infrastructure will enhance or deter equity.

Many were frustrated that the recent memo did not adequately consult members of the research publishing industry (Michael, 2022), but the memo is an opportunity to rethink open access altogether and perhaps change the conversation. The Indiana University-Bloomington Libraries’ International Open Access symposium on October 28, 2022, ignited engaging conversations about how the memo might impact the humanities and social sciences. Scholars from Columbia College-Chicago and Indiana University and publishers and press directors provided much food for thought on the memo’s implications.

Process over Product

A panel with Indiana University anthropology professors Ilana Gershon and Eduardo S. Brondizio acknowledged a theme that all other presenters at the symposium would address in different ways: a need to focus on processes rather than products. The term “open access” often focuses on publications as objects rather than part of greater research processes; publishing is only one means of sharing scholarship.

Whether it’s because of the open access movement’s neglect of the humanities, or the problematic academic incentives and reward systems in academia, or the confusing and labor-intensive (like free peer review) processes publishers propagate, open access is often not the highest concern when deciding where to publish in the humanities. The high cost to publish openly has heightened the status quo: publish dense, inaccessible texts in prestigious journals and publish accessible texts via open access. The inequities in open access are being used to legitimize poor publishing practices—let the academics keep their dense texts and the rest of the public will hold out for a less exclusive version.

Even though readerships in the humanities and social sciences often gravitate toward print, legacy funding and business models from the pre-virtual world aren’t working, and one of those legacies is the subscription model. In the digital world, why pay for content before it comes out? Why have content bundled into a serial subscription when they can be accessed on demand, as they are published? The memo’s zero embargo will likely make the subscription model unfeasible for many publishers.

Funding and Business Models

Our current system of publishing requires substantial financing to access and participate in research. Since its release, the memo has been criticized that because this is an unfunded quasi-mandate, the biggest priority should be to figure out how to realign funding. University administrations’ ideas for how funding should be allocated—through library budgets and research funds—don’t support a model where the principal researcher pays for open access because neither library budgets nor research funds are designed for this purpose.

Publishers make money from subscriptions, and the fact that the subscription model is already in jeopardy means that publishers might likely choose the “researcher pays” route to replace subscription revenue loss. This could set the stage for federally funded research and non-federally funded research, forcing journals to switch to an author pays only model, which leads to inequities (especially for underfunded early-career researchers) not only within the US but worldwide. On the other hand, this might motivate university libraries to join publish and read agreements to help researchers without federal funding.

The onus on researchers is a very real possibility that does not just threaten the sciences and scholarly journals. Even though the research infrastructure in the sciences is more financially robust, the cost of open access in the humanities and social sciences is significant. At the University of Indiana symposium, Alexa Colella, former acquisitions editor at the University of Illinois Press, explained why article and book processing charges in the humanities and social sciences are not as low compared to the sciences as one might expect, due to the unpredictability of revenue, royalties, and society sustainability. The National Endowment for the Humanities funds summer research for faculty and year-long support for scholars, but neither constitute the majority of funding needed to write a book (Anderson, Wulf, 2022).

Possible Actions and Directions

Almost all of the presenters at the Indiana University symposium made a call for a shift in how publishing needs to be funded. Eileen Joy, founder of Punctum Books, explicitly said that governments should take over publishing as a public good in support of publishing and research dissemination rather than funding research grants. Joy concluded her presentation by examining the directions libraries and universities might go in the face of unethical practices by monopoly publishers. Generally, there should be more encouragement and incentives, not barriers, for society publishing and other nonprofit organizations that conduct low-cost research and publishing. Additionally, marginalized scholars in particular have no choice but to play this game of high-cost open access publishing in order to be more widely seen, read, and to survive academically.

While the memo promotes equitable practices among the players in the scholarly publishing ecosystem, bibliodiversity, or publishing a variety of underrepresented voices, is not the goal. The memo cannot achieve a cultural change on its own—that can only be done by raising awareness of alternatives and highlighting the downsides of current approaches to publishing. Samuel Moore, scholarly communication specialist at Cambridge University Library, explains, “It is also important to reveal the ways in which research cultures shape how researchers decide to publish their work—often at the expense of experimentation and openness—and how they can be changed for the better… we must find a range of ways to support new cultures of knowledge production and dissemination in the university and beyond (Moore, 2022).

The University Libraries help WashU authors navigate the shifting open access publishing landscape, and have negotiated discounts on processing charges with several major publishers. For information and services, please visit:

Scholarly Communications—resources for facilitating the dissemination, accessibility, and impact of scholarship.

Open Scholarship—a repository that provides free and open access to the scholarly output, such as theses, dissertations, articles, and other research by students, faculty and staff.

Open Scholarship Journals and Open Scholarship Books—the Digital Library Program Services publishes journals hosted by the university, non-traditional scholarship, and long-form publications hosted on Pressbooks.

Works Cited

1. Nelson, A. MEMORANDUM FOR THE HEADS OF EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENTS AND AGENCIES. Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). 2022, August 25. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/08-2022-OSTP-Public-Access-Memo.

2. Piller, C, “Many scientists citing two scandalous COVID-19 papers ignore their retractions.” Science. 2021, July 15. https://www.science.org/content/article/many-scientists-citing-two-scandalous-covid-19-papers-ignore-their-retractions.

3. Michael, Ann, et al. “Ask the Chefs OSTP Policy I.” The Scholarly Kitchen. 2022, August 30. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2022/08/30/ask-the-chefs-ostp-policy-i/.

4. Anderson, R. et al. “Thoughts and Observations on the OSTP Responses to Our Interview Questions.” The Scholarly Kitchen. 2022, October 13. https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2022/10/13/thoughts-and-observations-on-the-ostp-responses-to-our-interview-questions/.

5. Moore, S. “Thoughts on the New OSTP Open Access Memo.” 2022, August 31. https://www.samuelmoore.org/2022/08/31/thoughts-on-the-new-white-house-ostp-open-access-memo/.