Helen Dryden: Illustrator and Industrial Designer in the Age of Art Deco

In the early twentieth century, the covers of the large publications were beautifully illustrated, and many artists who contributed became household names. The art created for fashion magazines in particular stands out. What had started out as representational drawings of clothing and models morphed into French Art Nouveau inspired covers, with thin, curvilinear lines, less intricate rendering, color flats, and compositions filled with decorative elements. This style soon transitioned into Art Deco, a visual mode that was heavily developed by illustrators of fashion.[i]

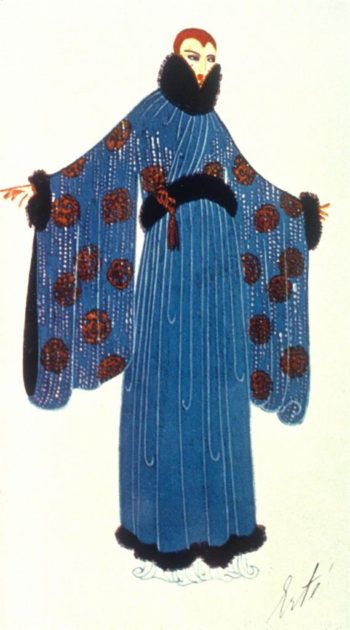

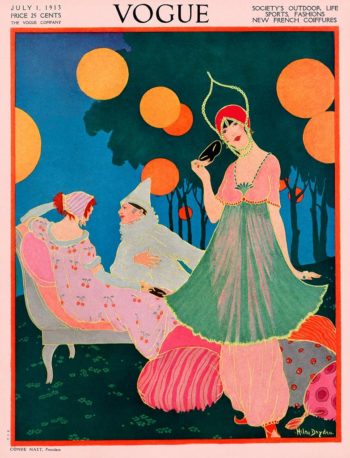

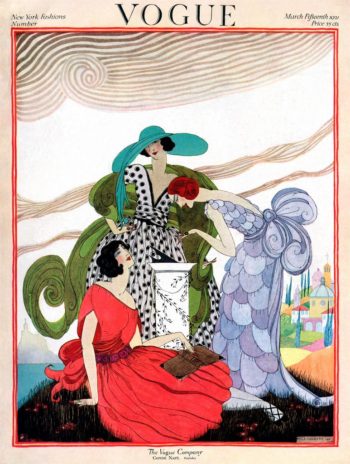

Artists such as Erté, Léon Bakst, Umberto Brunellischi, Georges Barbier, Etienne Drian, and Dulac all made names for themselves as illustrators for Harper’s Bazaar.[ii] All are male and European. The leading lady of this post, Helen Dryden, was conversely female and American. At the turn of the century in America, fashion illustration was still representative and unimaginative. Dryden was an important catalyst in introducing and popularizing similar European and Deco styles of illustration to America. By following Dryden’s images for Vogue, Delineator, and finally Studebaker, one can see how her work exemplifies changes in Art Deco from the 1910 to 1937.

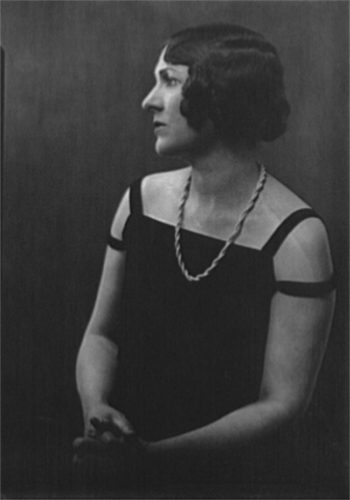

Dryden was born in Baltimore in 1882. She showed artistic promise from a young age, but never received much art training, and was mostly self-taught. She said of her work and her lack of formal training, “That is why my work is so entirely my own. It is a combination of things I like, in the way I want to do them, rather than an unconscious reflection of the ideas of an admired master.”[iii]

In 1909, Dryden moved to New York to sell her drawings to fashion magazines. She faced rejection repeatedly for a year’s time, but eventually received a deal with Vogue, which was under the art direction of Condé Nast at the time. This turned into a thirteen-year contract with the magazine, for which Dryden illustrated covers and interior articles.[iv]

Dryden’s first work for Vogue was published in 1910. Katherine McClinton states in her book, Art Deco: A Guide for Collectors, that Art Deco “thrived in the years between 1910 and 1935, reaching its high point between 1925 and 1935.”[v] This timeline closely parallels Dryden’s most prolific working period. Dryden’s key inspiration is also often associated with the start of Art Deco. Though Art Deco has its roots in Art Nouveau, The Ballet Russes in Paris and the costume designs and original drawings of Léon Bakst “had great impact on the decorative arts of the period.”[vi]

Dryden often cited Bakst, the Russian Ballet, and all things French as the inspiration for her inventive and fanciful drawings.[vii] Osbert Lancaster said, “[the] colors were the best and most lasting legacy of the Russian Ballet to Art Deco,” referring to “jade green, purple, every variety of crimson and scarlet, and above all orange.”[viii] Dryden wanted to bring Bakst’s vision and color to the American magazines, as she found the illustrations of the day to have a “blatant lack of appeal.”[ix] She achieved this in her work for Vogue.

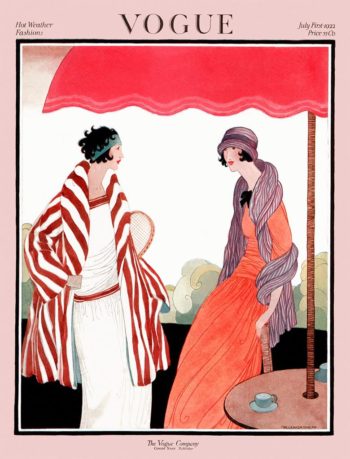

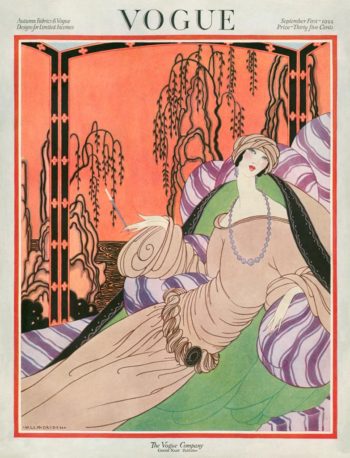

Dryden’s Vogue covers often depict at least one full figure woman, in an imagined setting and heavily applied decoration, be it dress patterns or surrounding floral elements. Her work for Vogue is a testament to early Art Deco, which was sinuous and more closely related to the Art Nouveau movement. The term Art Deco covers a lot of ground, and “not all art of the 1920s and 1930s is Art Deco, and not all Art Deco has the same characteristics. Early Art Deco has graceful, feminine forms, and later examples are characterized by cubist forms,”[x] as seen in Dryden’s later Delineator covers.

However, at Vogue, Dryden was part of the “phase of Art Deco [that] was tied to the rhythm of the times as reflected in the ballet and the designs of Bakst, Erté and Paul Iribe. This produced a gay, fanciful style that was still based on genuine values.”[xi] Like Erté and Barbier, two pioneers of Art Deco fashion illustration, Dryden drew her models in “a decorative and unrealistic manner.”[xii] Her work was decorative, bright, clean lined, and highly imaginative. She created a fabricated space around her models, filling the cover with swirling water or clouds, flora, and the occasional animal.

However, this style would in later years lose some of this “fanciful style” to streamlining and visions of industry. Some of this idea is evident in the Vogue drawings, as in one cover Dryden makes use of a spotted greyhound. Greyhounds became a symbol of the speed and efficiency of American industry. Bevis Hillier states, “Dogs were in favor, too, especially greyhounds and borzois, respectively suggested by the idea of streamlining and by the decorative dogs taken out by Hollywood stars.”[xiii] Erté in his famous “Symphony in Black” also used the greyhound. The greyhound is an early sign of Art Deco both using itself as a “statement of twentieth century modernity and technological progress,”[xiv] and as being “self-consciously new.”[xv]

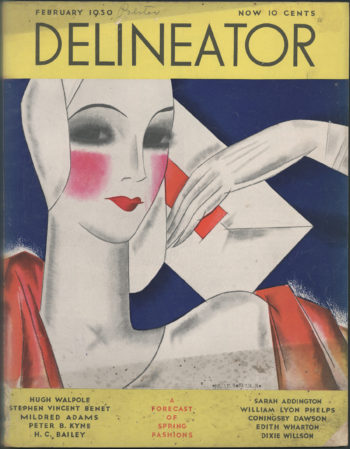

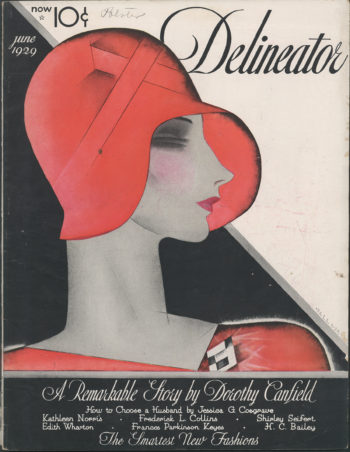

In 1923, Dryden became disassociated with Vogue, and soon after with her previously fanciful and Russian Ballet inspired images.[xvi] At this time she started making covers for The Delineator magazine. Delineator was a fashion magazine, which at the time when Dryden was contributing touted modern sensibilities. Its articles discuss modern fashions, wallpaper as a modern and easy method of interior decorating, as well as the rise of “talkies” in modern cinema. An article on kitchen efficiency from a 1929 issue shows the influence of Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s Frankfurt Kitchen design of just three years previous. One salient article discusses the modern home, and asserts the idea of the “machine for living,” in which home becomes a sleek, minimalist, efficient space. The article asks for decoration to be left behind, as it “practices a dead art.”

Similar trends are evident in the development of Art Deco in the late 1920s. Deco artists began adapting avant-garde ideas[xvii] as well as employing the function of streamlining their drawings to “create and establish an art expressive of their times. This meant the acceptance of speed and intensity and a breakdown of traditional patterns.”[xviii] By 1928, the feminine, graceful visuals of Art Deco as seen in Dryden’s Vogue covers were in decline.[xix] Deco was now dominantly influenced by the ideas of cubism, and “new young designers favored the stark simplicity, austerity and innovations of modern life and industry.”[xx]

These changes are on full display in Dryden’s Delineator covers; they are starkly different from her Vogue work. Her Vogue covers, as described above, are whimsical, imaginative, and notably decorative illustrations of full figures. For The Delineator however, the crop is tighter; the majority of her covers are of women from the collarbone up, in a sense streamlining the image to its essential parts. The colors are more muted, her lines fuzzier, and above all lacking in the decoration that the writers of the Delineator articles, and other practitioners of Art Deco, found redundant. Similar to the modern home, Dryden’s illustrations have been stripped down to what is most efficient and streamlined. Some of the works take on a cubist mentality, with intersecting lines and shapes that create dress forms and flowers. Dryden’s visages also undergo a change, looking similar to Brancusi’s “Muse,” and the art of Deco painter Jean Dupas, who “tended to dehumanize his characters, turning them into pretty, sharp-featured but expressionless mannequins.”[xxi]

Dryden’s Delineator women further show Art Deco’s reflection of modernity and industry by their actions. In the covers selected from the Modern Graphic History Library collection, one woman is driving her own car; another applies makeup on the go with a compact. A third woman, whom one could describe as a “30s sophisticate with her dyed platinum hair,”[xxii] holds a scarf while a steamship chuffs along in the background. Lastly, a woman enjoys a cup of tea with lemon at a café during her modern free time, thanks to the efficiency of industry. Dryden, with her streamlined illustrations and depictions of modernity, is testament to Léon Deshairs’ line from Modern French Decorative Art, “Today the decorator frankly borrows all the motifs he can from industry.”[xxiii]

Industry was Dryden’s next career move. She was the art director of the Dura Company in Ohio, and most notably was hired by Studebaker as an industrial designer from the mid 1930s until 1937.[xxiv] There, she designed the interior of the Studebaker President, and worked alongside Raymond Lowey, who designed the exterior.[xxv] At the time, Dryden was retained for $100,000 a year, giving her the title of “highest-paid woman artist.”[xxvi] Dryden’s name even appeared in advertisements and articles for the vehicles that she worked on. One ad proclaims, “It’s Styled by Helen Dryden,” showing Dryden’s position as a household name and respected artist. In an article about the Cleveland Great Lakes Exposition in the June issue of Life, the 1937 Studebaker’s interior is described as “refreshingly ventilated and generously roomy, …tastefully and distinctively styled by famous Helen Dryden, America’s “first lady” of design.”[xxvii] An advertisement for the $665 Studebaker notes “the charm of the interiors that only gifted Helen Dryden could achieve.”[xxviii]

As an industrial designer, Dryden was part of a phase that was particularly American to Art Deco. The appeal of mass production rose after the 1929 stock market crash, but products still needed to appeal to consumers.[xxix] This is where industrial designers and Art Deco themes came in. Streamlining of products in America was a popular design choice. Though not American of origin, streamlining’s “widespread application in the 1930’s to the design of vehicles and stationary consumer goods was America’s distinctive contribution to the development of Art Deco.”[xxx] Streamlining in industrial products also served as a symbol of science and rationale, which had the effect of seducing customers.[xxxi] Similarly, Dryden and other industrial designers were seen as “logical and mature leaders of the country’s indigenous design movement, who had ‘grown up’ past the need for ‘childish effort’ in decoration.”[xxxii]

Dryden’s work follows the phases of Art Deco, ending with her work as an industrial designer. Helen Dryden was a product of the stylistic developments of Art Deco, and even though she may not have believed that decoration was a “childish effort” that needed to be grown out of, she evolved as an artist and kept up with the times. Dryden’s contribution to and relative notoriety during the Art Deco movement (not to mention her success as a woman artist), makes it a shame that she is not better known today. My research for this blog post almost only contained men who were part of the Art Deco period. Helen Dryden, and perhaps other such women artists now lost to time, deserve to be mentioned in the same ranks of men.

Sources

[i] Victor Arwas, Art Deco, Rev. ed (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1992).

[ii] Katharine Morrison McClinton, Art Deco; a Guide for Collectors, 1st ed. (New York: C. N. Potter; distributed by Crown Publishers, 1972).

[iii] “Notes,” Biographical Cyclopaedia of American Women 2 (1925): ix–304.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] McClinton, Art Deco; a Guide for Collectors.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] “Notes.”

[viii] Bevis Hillier, Art Deco of the 20s and 30s, Rev. ed (New York: Schocken Books, 1985).

[ix] “Notes.”

[x] McClinton, Art Deco; a Guide for Collectors.

[xi] Ibid.

[xii] McClinton, Art Deco; a Guide for Collectors.

[xiii] Hillier, Art Deco of the 20s and 30s.

[xiv] Carla Breeze, American Art Deco: Architecture and Regionalism, 1st ed (New York: W.W. Norton, 2003).

[xv] Hillier and Escritt, Art Deco Style.

[xvi] William Packer and David Hockney, Fashion Drawing in Vogue (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1989).

[xvii] Arwas, Art Deco.

[xviii] McClinton, Art Deco; a Guide for Collectors.

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] Ibid.

[xxi] Arwas, Art Deco.

[xxii] Ibid.

[xxiii] McClinton, Art Deco; a Guide for Collectors.

[xxiv] Carroll Gantz, Founders of American Industrial Design (McFarland, 2014).

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] Ibid.

[xxvii] Time Inc, LIFE (Time Inc, 1937).

[xxviii] Time Inc, LIFE (Time Inc, 1936).

[xxix] Charlotte Benton et al., eds., Art Deco 1910-1939, 1st North American ed (Boston: Bulfinch Press/AOL Time Warner Book Group, 2003).

[xxx] Ibid.

[xxxi] Ibid.

[xxxii] Ibid.

Bibliography

- Arwas, Victor. Art Deco. Rev. ed. New York: H.N. Abrams, 1992.

- Benton, Charlotte, Tim Benton, Ghislaine Wood, and Victoria and Albert Museum, eds. Art Deco 1910-1939. 1st North American ed. Boston: Bulfinch Press/AOL Time Warner Book Group, 2003.

- Breeze, Carla. American Art Deco: Architecture and Regionalism. 1st ed. New York: W.W. Norton, 2003.

- Gantz, Carroll. Founders of American Industrial Design. McFarland, 2014.

- Hillier, Bevis. Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. Rev. ed. New York: Schocken Books, 1985.

- Hillier, Bevis, and Stephen Escritt, eds. Art Deco Style. London: Phaidon, 1997.

- Inc, Time. LIFE. Time Inc, 1936.

- ———. LIFE. Time Inc, 1937.

- McClinton, Katharine Morrison. Art Deco; a Guide for Collectors. 1st ed. New York: C. N. Potter; distributed by Crown Publishers, 1972.

- “Notes.” Biographical Cyclopaedia of American Women 2 (1925): ix–304.

- Packer, William, and David Hockney. Fashion Drawing in Vogue. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1989.

This post is part of a series published by students in D. B. Dowd’s Spring 2017 course Special Topics in Visual Culture: The Illustrated Periodical.