Harmonizing the Disharmonious: Robert Coover and the MLC, Part I

To celebrate Robert Coover’s upcoming visit to Washington University for a Neureuther Library Lecture Series reading on November 1, 2016, we are highlighting Coover materials in the Modern Literature Collection. The following is the first of a three-part series.

Robert Coover and the International Writers Center

Robert Coover is known for the remarkable scope of his writing, not only in the enormous breadth of subjects and conflicts–a mining disaster in Order of the Brunists (1966), the threat of global communism in The Public Burning (1977), and the murder of an actress in Gerald’s Party (1986), to name a few–but in the conflicted, conflicting, polyvocal nature of their narratives, the many-layered whisperings that lay deep (often lost) in their construction. Through his widely varied explorations in form–from political fable to fairy tale, from noir to erotica, from screenplays to hypertext–Coover deconstructs the multitude of mythologies, archetypes, and cultural performances complicit in the telling of his own stories, bringing these internal conversations to the surface.

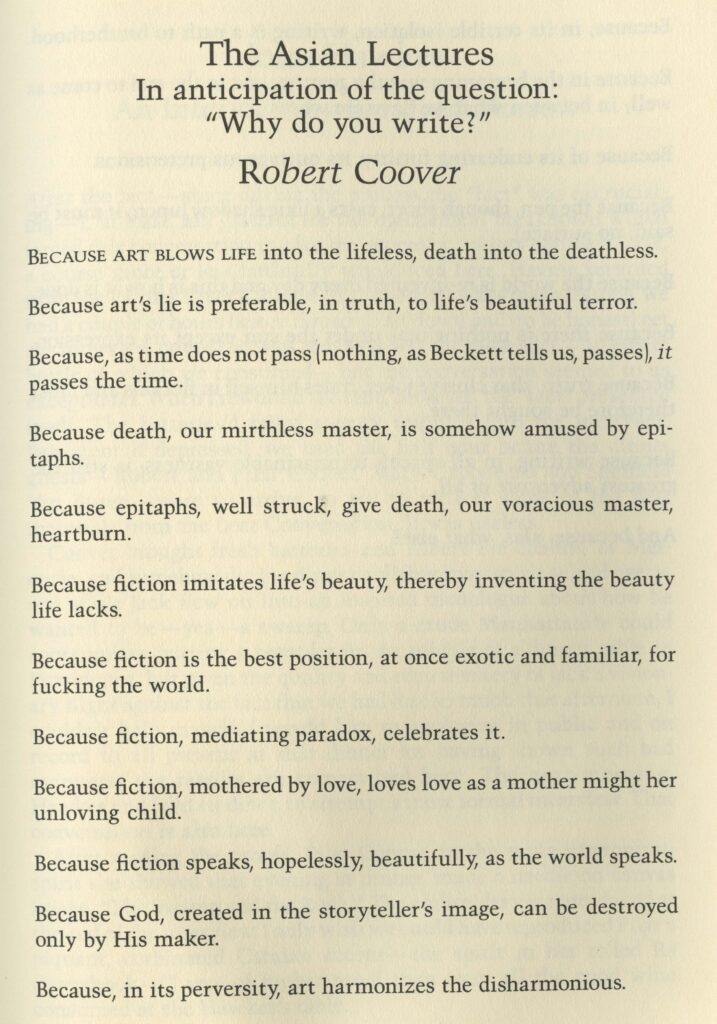

Coover’s devotion to self-examining fiction resonates in his 1988 piece–“In anticipation of the question ‘Why do you write?'”–in the 12th issue of Conjunctions:

Herein – as in all of his work – Coover embraces the conflicts and paradoxes inherent to art’s creation: “Because fiction speaks, hopelessly, beautifully, as the world speaks…Because, in its perversity, art harmonizes the disharmonious.”

In keeping with his interest in “the world [as it] speaks,” Coover served as an active facilitator of conversations between writers. He was an instrumental organizer for the International Writers Project at Brown University (where he taught from 1981-2012) and a board member of the International Writers Center (IWC) at Washington University. As a friend of IWC director and co-founder William H. Gass, Coover organized and hosted IWC panels, including a heated discussion at the center’s premiere 1992 conference, “The Writer in Politics.”

Here, Coover introduces Somalian writer Nuruddin Farah as a writer who is “not so privileged” by the governing institutions that allow (and prohibit) the existence of political writing, opening with a question of how writers can explore “the problems and solutions” of working under a repressive regime.

Here, Coover mentors discussion between Farah and the members of his panel, questioning whether or not all writers are politically “in the same boat” (and if there is a certain degree of privilege implicit in this idea). He thus slyly proffers a question of artistic ethos versus the (profiteering) aims of publishing, insinuating that writers–most especially writers “not so privileged”–must maneuver subversively within the language of their region in order to speak “as the world speaks.”

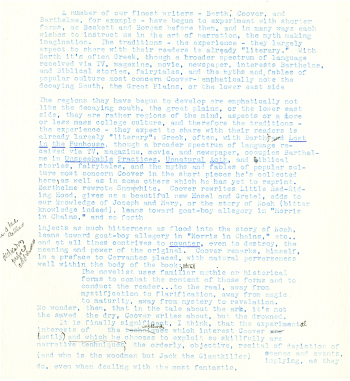

William H. Gass vocally expressed his admiration for the “broader spectrum” of language Coover’s writing engaged with. In a 1969 review of Coover’s short story collection Pricksongs & Descants, Gass illuminates Coover’s role as an instructor in “the art of narrative” among a host of great scholars–Barth, Barthelme, Beckett, and Borges–examining their legacy of story-telling traditions.

This review led to a correspondence between Gass and Coover and–ultimately–the establishment of a literary friendship.

Here is a video of writer Ariel Lewis reading from Coover’s letter to Gass nearly 45 years after its composition, at the MLC50 celebration in November 2014.

For more footage of Robert Coover related to the Modern Literature Collection, visit the MLC’s Digital Archive.