“Rebel City in a Rebel State”: From the Desk of William Greenleaf Eliot

In the fall of 1861, the escalating Civil War had thrown Missouri into turmoil. As a border state that remained in the Union yet one that continued to practice slavery, Missouri was in a complicated position. Union general John C. Frémont had declared martial law, and soon all property, including slaves, belonging to dissenters could be confiscated for army use. Since most of the St. Louis’s population sided with the South, this declaration caused utter social and economic havoc in city and countryside.

By the time war broke out, Unitarian minister William Greenleaf Eliot had become heavily involved in getting the fledgling Washington University off the ground through securing funds and land. Now it seemed as though all of his work might be lost. He took it upon himself to write to the Secretary of the Treasury, Salmon P. Chase on September 8th in order to ask for President Abraham Lincoln’s assistance in protecting St. Louis.

In his letter, Eliot emphasized the urgency of the situation, writing, “My desire is to call your attention to the critical condition of Missouri, and the necessity of a vigorous policy & strong measures to save it from complete utter devastation.” In Eliot’s view, spies were taking advantage of the city’s lack of standing army by secretly inviting floating Southern troops to take St. Louis as a choke point on the Mississippi.

Eliot referred to the recent territorial losses experienced by General Frémont in Missouri. By the end of the September, however, the Union army’s fortunes had reversed, as the Confederates made a retreat for Arkansas and Mississippi.

A majority of St. Louisans at the time favored secession, and Eliot feared that the city might capitulate. He ended his letter to Chase with a direct plea: “Pardon my intrusion. My whole heart is this cause. The war of Barbarism against Civilization, of Slavery against Freedom, is the great event of the 19th C[entury].” Eliot’s use of slavery and freedom referred to his own growing public reputation as an abolitionist, but it also hints at the contemporary practice of using liberation as a metaphor for national union.

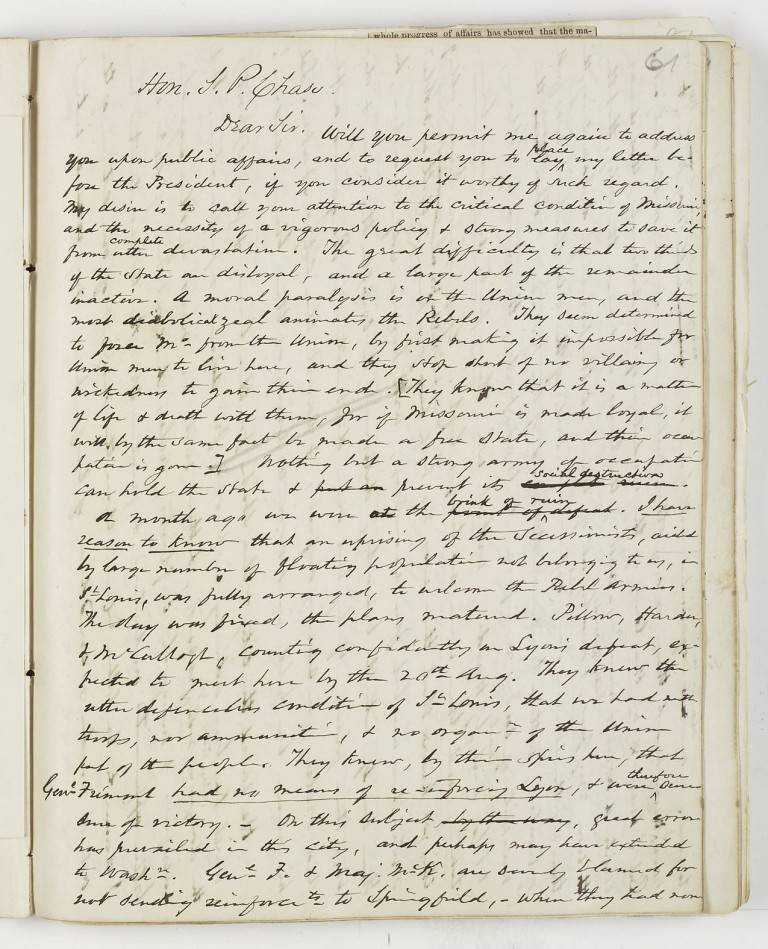

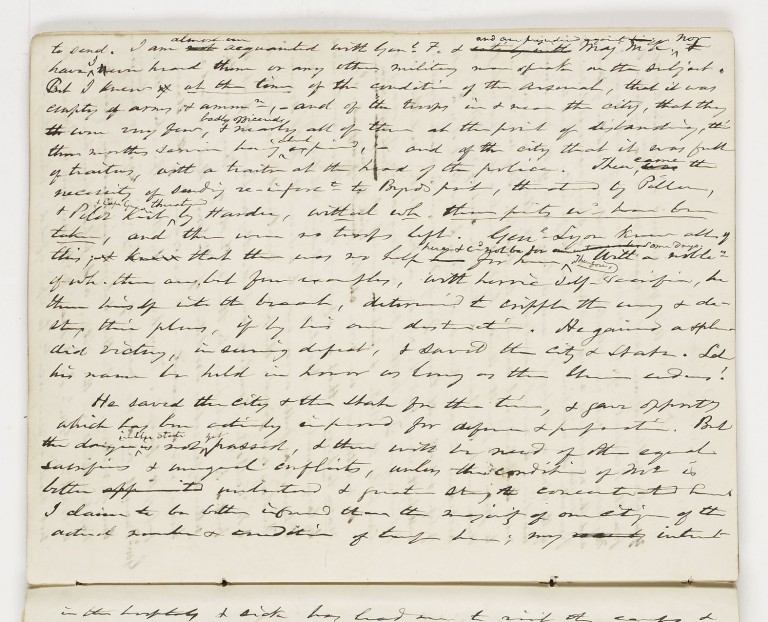

Hon. J. P. Chase. Dear Sir, Will you permit me again to address you upon public affairs, and to request you to lay ^place my letter before the President, if you consider it worthy of such regard. My desire is to call your attention to the critical condition of Missouri, and the necessity of a vigorous policy & strong measures to save it from complete utter devastation. The great difficulty is that two thirds of the State are disloyal, and a large part of the remainder inactive. A more paralysis is on the Union men, and the most diabolical zeal animates the Rebels. They seem determined to force M[iss]o[uri] from the Union, by first making it impossible for Union men to live here, and they stop [illegible] of no villainy or wickedness to gain their end. [They know that it is a matter of life & death with them, for if Missouri is made loyal, it will be the same fact be made a free state, and their occupation is gone.] Nothing but a strong army of occupation can hold the state & prevent its social destruction. A month ago we were at the brink of ruin. I have reason to know that an uprising of the Secessionists, aided by large number of floating population not belonging to us, is St. Louis, was fully arranged, to welcome the Public Armies. The day was fixed, the plans matured. Pillow, Hardee & McCullogh, counting confidently on Lyon’s defeat, expected to march here by the 20th Aug[ust]. They knew the utter defenseless condition of St. Louis, that we had neither troops, nor ammunition, & no organization of the Union part of the peoples. They knew, by their spies here, that General Fremont had no means of reinforcing Lyon, & were therefore sure of victory. On this subject by the way, great error has prevailed in this city, and perhaps may have extended to Washington. Genl F. & Major: McK. [Justin McKinstry] are surely blamed for not sending reinforc[emen]ts to Springfield, – when they had none to send…no one can tell whom to trust. Political, moral & social consideration are so mixed together, that men who ought to be true prove false, and a [illegible] necessary [dwells?] upon the Commander in chief to oversee & inspect by this for himself. Pardon my intrusion. My whole heart is this cause. The war of Barbarism against Civilization, of Slavery against Freedom, is the great event of the 19th C[entury]. May God protect the right. Y[ou]rs. truly, — Copied & Sent Sept. 8th 1861

Series 01, Notebook 6, pages 61-62

To find out more about Eliot, please consult the William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers located at the University Archives and this library research guide.

You can read more of Eliot’s online collection by perusing his materials at Missouri Digital Heritage.

Sources

- Miranda Rectenwald and Sonya Rooney, “‘Shall we be one strong united people…’” The Confluence, Spring/Summer 2011.