Eulogy for Freeman George: From the Desk of William Greenleaf Eliot

As a prominent Unitarian minister in nineteenth-century St. Louis, one of William Greenleaf Eliot’s religious responsibilities was to prepare and deliver funerary sermons for deceased members of his congregation. In 1860, during a brief reprieve before the advent of the Civil War, Eliot drafted such a eulogy in his notebook for one Freeman George, a St. Louis native who had recently committed suicide. The details he includes of the man’s life are tragic, gruesome, and revelatory, and provide a window into antebellum St. Louis. In his eulogy, Eliot describes the 1858 fire on the steamboat Col. Cressman. The vessel had been making its way up the Mississippi River from New Orleans when its engine exploded near New Madrid in southern Missouri, an accident that killed around half of its forty passengers. The New York Times reported on the fire, stating,

The boat at once caught fire. The Captain ordered out the yawl, but the deck hands and firemen took possession of and filled it, and would not get out. The other boat was ordered out, and into this the officers crowded as many passengers as possible, and they made their way safely to New Madrid. The officers of the steamer, and such of the passengers as had not got into the boat, jumped into the river. Some made their way to the shore without aid, and others were saved by a skiff put out by other persons who saw the disaster. The boat floated, burning, three miles and a half, when she lodged on a bar and burnt down to the water.

The New York Times, New York, 1858-02-11

The article lists Freeman George as one of the survivors, but the experience, as his friends and family later noted, scarred him and possibly caused his future emotional and psychological distress. After this terrible accident, George attempted to start his life over again. He fought for the Mexican Liberal Army in the Reform War of 1857-1861, but hunger and exposure on the front worsened his physical condition. Upon returning to St. Louis, he tried to find employment and actively participated in Eliot’s congregation. However, according to the minister, George’s recent personal tragedies led him down the path of moral depravity, and the night before his death he was seen carousing with prostitutes, gambling, and drinking on a docked showboat. He jumped off the side into the depths of the Mississippi the next day, a water-logged letter to his mother found wedged in his coat pocket. George’s story shows that everyday life in 1850s St. Louis was full of opportunities for self-improvement but also fraught with danger. Although no longer a sleepy frontier town, it still provided individuals with social and cultural freedoms not available in larger, more established cities. This episode also reveals the extent to which Eliot was involved in the lives of his parishioners, and his concern for their moral and spiritual state.

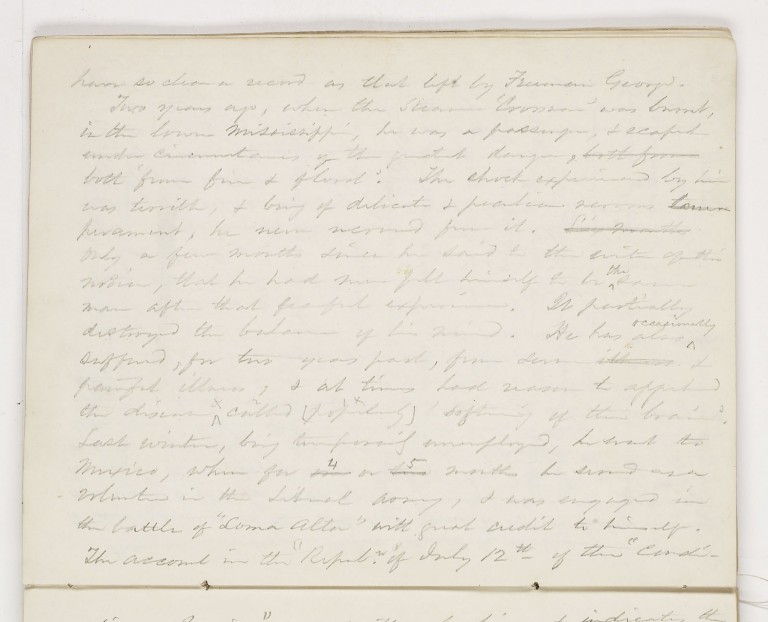

The passage reads: “Two years ago, when the Steamer ‘Cressman’ was burnt, in the lower Mississippi, he was a passenger, & e[s]caped under circumstances of the greatest danger, but from both from ‘fire & plume’. The shock experienced by him was terrible, & being of delicate & fractious nerves tem permanent, he never recovered from it. Six months Only a few months since he said to the evil of this notion, that he did not feel himself to be the same man after that fearful experience. He partially destroyed the balance of his mind. He has also [^occasionally] suffered, for two years past, from some illness painful illness & at times had reason to approach the decision and called (popularly) ‘softening of the brain’. Last winter, being temporarily unemployed, he went to Mexico, where for 4 or 5 months he served as a volunteer in the Liberal army, & was engaged in the battle of “Loma Alta” with great credit to himself. The account in the “Repub[lican]” of July 12th…”

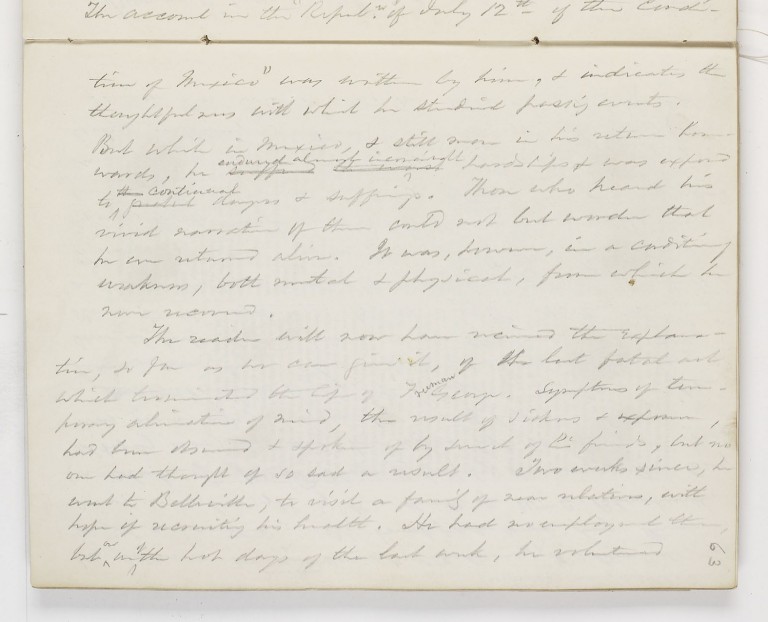

The passage reads: “‘The Condition of Mexico’ was written by him, & indicates the thoughtfulness with which he studied passing events. But while in Mexico, & [illegible] in his setting home-wards, he suffered [^endured almost inconceivable] hard life & was exposed to [^the continual] partial dangers & sufferings. Those who heard his vivid narration of them could not but wonder that he had returned alive. He was, however, in a condition of weakness, both mental and physical, from which he was uncured. The water will now have uncovered the explanation, as far as he can find it, of the last fatal and which transmitted the life of ^Freeman George. Symptoms of time – passing of mind, the result of sickness & exposure, had been observed & spoken of by much of his friends, but no one had thought of so sad a result.”

To find out more about Eliot, please consult the William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers located at the University Archives and this library research guide.

You can read more of Eliot’s online collection by perusing his materials available online at Missouri Digital Heritage.

Sources

- William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers; “New Madrid MO Steamer Col. Cressman Burns,” The New York Times, February 11, 1858.