Letters to Family: From the Desk of William Greenleaf Eliot

The William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers also include correspondence from Eliot to family members, friends, and prominent individuals written throughout his lifetime. Some of these letters date to the Civil War period and provide an intimate portrayal of everyday life in a war-time border state. They also reveal Eliot sharing his thoughts and opinions on abolitionism with direct and plainspoken language, something he usually avoided.

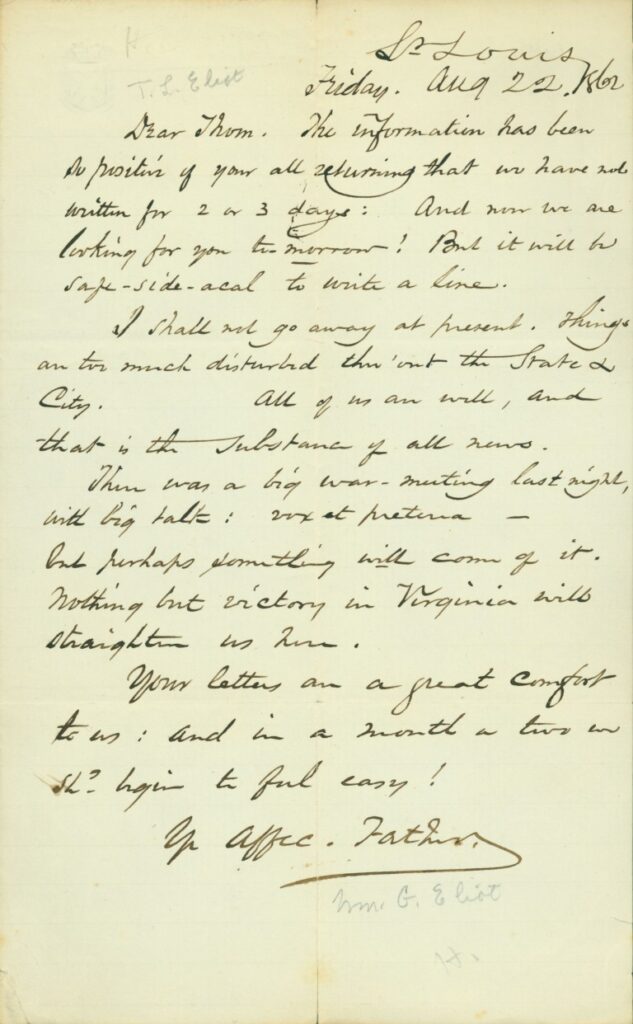

The first letter featured here was written in August of 1862 by Eliot to his son Thomas Lamb Eliot, who that year had joined the Missouri Home Guard, a local standing militia that contained both Union and Confederate sympathizers. He enlisted as a soldier after partaking in Washington University’s first graduation ceremony. In his letter, Eliot wrote to his son that both city and state were both so immersed in war that he would find it difficult to travel. He also mentioned that a war meeting took place the night before, but that he was skeptical that it would amount to tangible political and financial support for St. Louis. “Nothing but victory in Virginia,” he commented, “will straighten us here.” Both of these inclusions point to the difficulties of everyday life in St. Louis that year.

St. Louis Friday. Aug[ust] 22. 1862

Dear Thom. The information has been so positive of your all returning that we have not written for 2 or 3 days: And now we are looking for you tomorrow! But it will be safe-side-acal to write a line. I shall not go away at present. Things are too much disturbed thru’ out the State & City. All of us are well, and that is the substance of all news. There was a big war-meeting last night, with big talk: vox et praeterea — but perhaps something will come of it. Nothing but victory in Virginia will straighten us here. Your letters are a great comfort to us: and in a month or two we sh[oul]d begin to feel easy!

Y[ou]r Affec[tionate].

Father W[illia]m G. Eliot

Aug[ust].22 Lexington.

Series 02, Box 01, Folder 1862, 22 Aug

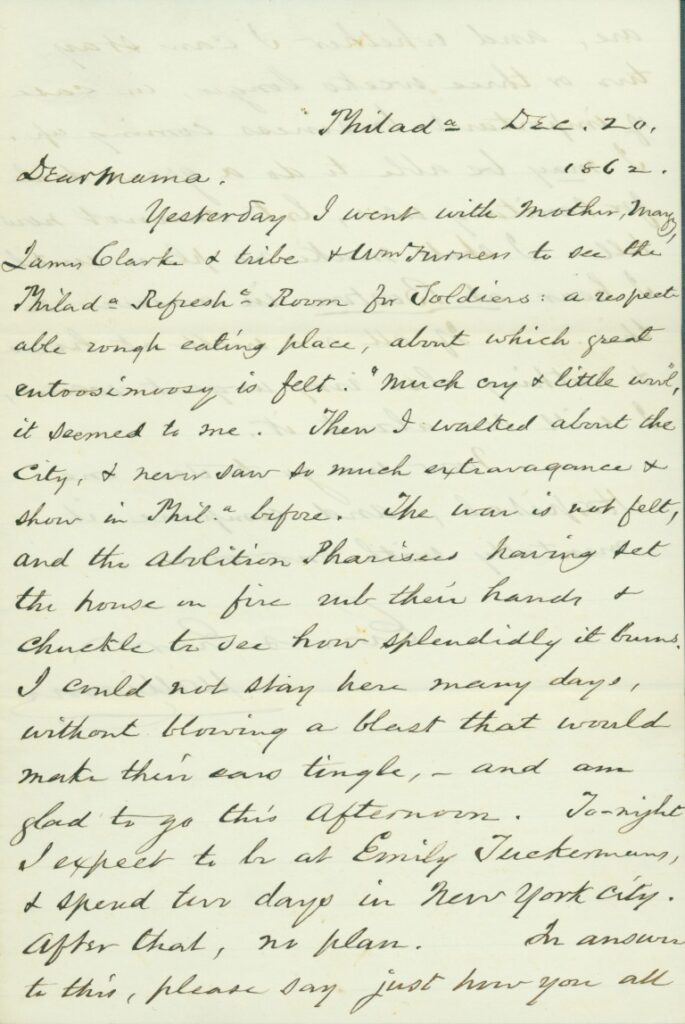

The next letter also dates to December of 1862 and was likewise addressed to a family member, in this case “Mama,” or Eliot’s wife Abigail Adams Cranch, who remained in St. Louis while he travelled northeast to visit his family. Here, Eliot reveals his true resentment for Boston-based abolitionists, who he called “Pharisees.” He described their attempts to sabotage the entire anti-slavery movement, a situation that filled him with so much rage that it influenced his decision to leave Boston early for New York City. He also recalled his time spent in Philadelphia, where he visited the Soldiers Refreshment Saloon, a bar maintained and financed by the city’s residents where Union soldiers could eat and drink for free. About it he wrote, “‘Much cry & little wool’” it seemed to me,” a figure of speech basically meaning “much ado about nothing.”

Philad[elphi]a

Dec[ember] 20, 1862.

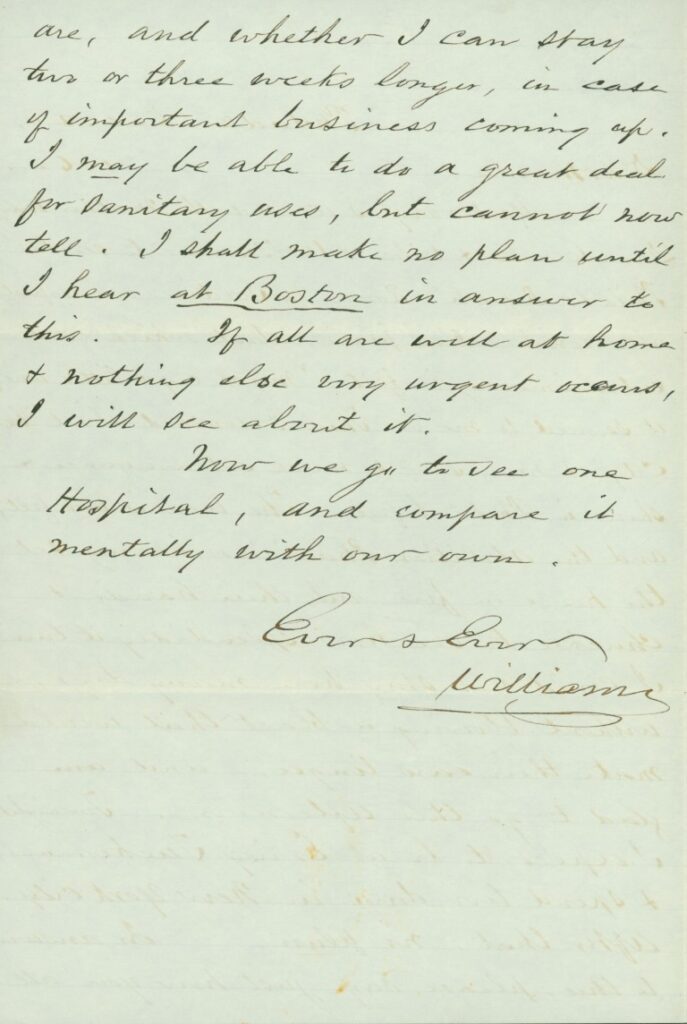

Dear Mama. Yesterday I went with Mother, May James Clarke & tribe & W[illia]m Turner to see the Philad[elphi]a Refresh[men]t Room for Soldiers: a respect able rough eating place, about which great entoosimoosy is felt. “Much cry & little wool,” it seemed to me. Then I walked about the city, & never saw so much extravagance & show in Phil.[adelphi]a before. The war is not felt, and the abolition Pharisees having set the house on fire with their hands & chuckle to see how splendidly it burns. I could not stay here many days, without blowing a blast that would make their ears tingle, — and am glad to go this afternoon. To-night I expect to be at Emily Tuckermans, & spend ten days in New York City. After that, no plan. In answer to this, please say just how you all are, and whether I can stay two or three weeks longer, in case of important business coming up. I may be able to do a great deal for sanitary uses, but cannot now tell. I shall make no plan until I hear at Boston in answer to this. If all are well at home & nothing else very urgent occurs, I will see about it. Now we go to see one Hospital, and compare it mentally with our own.

Ever & ever

William

Series 02, Box 01, Folder 1862, 20 Dec

Other individuals mentioned Philadelphia’s Soldiers Refreshment Saloon. In contrast to Eliot’s civilian view, Henry Coddington Meyer, a Union soldier, described his experience there: “On landing at Walnut Street wharf I went into the soldiers’ refreshment room, maintained by the citizens of Philadelphia, which was open night and day, and at which all soldiers passing through the city were fed free of charge. It was about two o’clock in the morning, very hot, and I was tired and depressed. Hence, when invited to partake of some refreshments, I was unable to do so but contented myself with eating a few pickles.”

To find out more about Eliot, please consult the William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers located at the University Archives and this library research guide. From the research guide you can link to more of Eliot’s online collection by perusing his materials at Missouri Digital Heritage, including more correspondence.

Sources

- Henry Coddington Meyer, Civil War Experiences under Bayard, Gregg, Kilpatrick, Custer, Raulston, and Newberry, 1862, 1863, 1864.