Religion and the Civil War: From the Desk of William Greenleaf Eliot

In the days and months leading up to the Civil War, Missouri was torn by the decision of whether or not to secede from the Union. As a slave-holding border state with a population divided over slavery, it had no easily discernible political alliances. Many of St. Louis’s inhabitants owned slaves or were otherwise sympathetic to the Southern cause, while others were fiercely anti-slavery. For instance, the Radical Republican Party had roots in St. Louis, as prominent individuals like General John C. Frémont and his wife Jessie Benton Frémont were partisans who spread their influence locally.

Although a moderate abolitionist and Union supporter, before the war Eliot rarely, if ever, came out publically regarding his political preferences. Rather, he preferred to preach broadly on the subjects of freedom, loyalty, and religion to his parishioners, arguing for the moral and ideological justification of united. Neighbors should avoid quarreling with neighbors over small details, and recognize together the importance of upholding unity. He urged St. Louisans not to quibble over small matters, especially when petty arguments could potentially end in street violence. The very placement of the United States in world affairs would remain vulnerable as long as ordinary Americans fought over party affiliations. As Rev. Dr. Earl K. Holt III describes in his book William Greenleaf Eliot: Conservative Radical, “Close friends of long standing would no longer even greet one another on the street. Members of the same St. Louis families enlisted in the opposing armies.” The strong passions aroused over the subject of slavery are especially damaging, since polarities in opinion keep citizens from reaching a compromise on the issue.

The following excerpt comes from Eliot’s early drafts of a sermon called “On Loyalty and Religion,” in which he argued that American citizens had a religious and patriotic duty to their nation that were one and the same. Along with serving his congregation through public sermons, Eliot also worked hard to keep Washington University afloat during the Civil War, even teaching metaphysics without pay to keep operating costs down. His years of tireless service paid off, as both the Church of the Messiah and the university survived the 1860s.

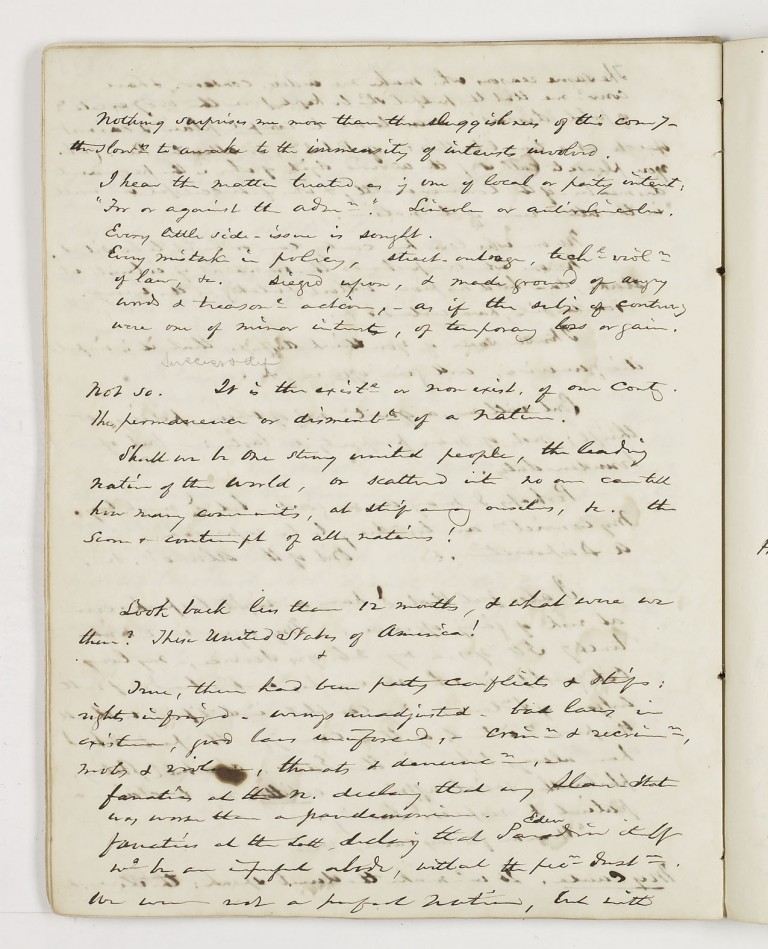

Nothing surprises me more than the sluggishness of this country – the slowest to awake to the immensity of intents involved. I hear the matter treated as if one of local or party intent: “For or against the administration.” Lincoln or anti-Lincoln. Every little side-issue is sought. Every mistake in policy, street-outrage, technical violation of law, etc. Seized upon, & made ground of angry words & treasonable action, – as if the subject of country were one of minor interests, of temporary loss or gain. Not so. It is the existence or non-existence of our country. The permanence or dismemberment of a Nation. Shall we be one strong united people, the leading nation of the world, or scattered into, no one can tell how many communities, at strife among ourselves, to the scorn and contempt of all nations! Look back less than 12 months, & what were we then? These United States of America! & True, there had been party conflicts & strifes; rights infringed – wrongs unadjusted – bad laws in existence, good laws unenforced, – criminations & recriminations, mobs & violence, threats & denunciations, – fanatics at the North declared that any Slave State was worse than a pandemonium. Fanatics at the South declaring that Eden / Paradise itself would be an imperfect abode, without the Peculiar Institution. We were not a perfect Nation, but with stains enough upon our escutcheon, weakness & sins enough; with too much boasting, too little self-respect.

William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers, Series 01, Notebook 6, page 36.

To find out more about Eliot, please consult the William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers located at the University Archives and this library research guide.

You can read more of Eliot’s online collection by perusing his materials available online at Missouri Digital Heritage.

Sources

- Rev. Dr. Earl K. Holt III. William Greenleaf Eliot: Conservative Radical. Belleville, Illinois: Village Publishers, 2011.

- William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers, Series 01, Notebook 6, page 36. (Printed sermon available in collection in Series 04, Box 02, 1861. 18 August. “Loyalty and Religion: A Discourse for the Times” delivered in the Church of the Messiah, St. Louis.)