From the Desk of William Greenleaf Eliot

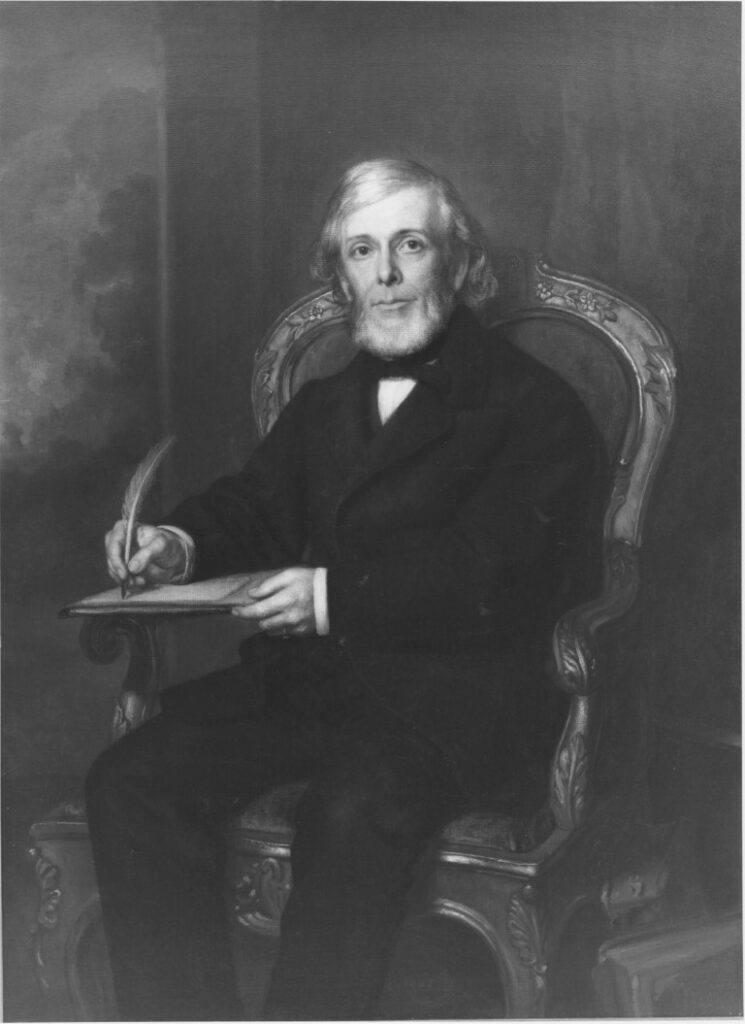

Today’s post commemorates the two hundred and first birthday of William Greenleaf Eliot, civic reformer, abolitionist, and co-founder of Washington University in St. Louis, who was born on August 5th, 1811. To celebrate his legacy, Bears Repeating will feature a monthly entry on Eliot, each one focusing on his selected writings found in the William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers housed at the University Archives. Each post will provide historical background and context for the selection, and will include an image of the document with a transcription of its contents. We will cull from his notebooks, letters, and sermons so that the general public can learn more about his life and times.

Eliot was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts to a wealthy shipping family. He attended Colombian College in Washington D.C. (now known as George Washington University), and worked for a while as a post office clerk. After attending Cambridge Divinity School he became a practicing Unitarian minister. When he was twenty-three years old he left New England to work as a missionary to the Osage indigenous group near St. Louis, founding the first Unitarian Church west of the Mississippi, the First Congregational Society of St. Louis. By 1830, St. Louis had around fourteen thousand inhabitants, but compared to Boston Eliot saw it as a frontier backwater. Most of the residents descended from the area’s first French settlers, but there were also recent emigrants who arrived shortly after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803.

But with time, Eliot became an incredibly prominent and influential citizen, and did much work to reform St. Louis. He worked to establish the city’s public schools, and helped to create the Western Sanitary Commission with his friend James B. Yeatman to combat disease and devastation in the last years of the Civil War. He helped to co-found Eliot Seminary, later renamed Washington University, with Wayman Crow, another prominent St. Louisan, and began work raising funds for the fledgling college. Eliot became the university’s third chancellor in 1870, holding the position until his death.

In addition to his work as an abolitionist, Eliot was sympathetic to temperance movements, and was an ardent believer that without moral and social improvement in individuals, no institutional or political reform would be possible. He approached all of his civic and religious responsibilities with this attitude in mind, which permeated every facet of his life. As it would seem, Eliot experienced internal conflict because of contradictory impulses. Although a fervent abolitionist, he was vocally non-partisan and supported gradual emancipation, citing the social and economic role slavery played in his society. Regardless, he was still a radical for his day, calling the battle between freedom and slavery “the most important problem of the nineteenth century.” Eliot advocated gradual emancipation of Missouri’s slaves, which may seem to some modern observers as conservative abolitionism. However, as Rev. Dr. Earl K. Holt III states in his book William Greenleaf Eliot: Conservative Radical, “One thing is clear. Eliot had a deep understanding of slavery and the society of which it was a part. He knew it not as abstract evil, but as a heinous personal and social reality, deeply ingrained in the social and economic structures of the South.”

In the years before the Civil War, Eliot attempted to reconcile his moderate abolitionism with his desire to avert Missouri’s secession from the Union. He wrote to prominent state politicians, pleading with them to compromise with Washington D.C. In 1849, he wrote to state senator Thomas Benton, who was vocally pro-slavery. In his letter, Eliot tried to appeal to the senator’s better moral nature, to be a stalwart for abolitionism, and to set an example for all Missourians. Eliot’s actions seem at once naive, stubborn, and admirable, as he tried to argue for gradual emancipation to a Southern sympathizer.

Apparently, Eliot, with the help of his abolitionist friends in St. Louis, may have had a hand in successfully changing Benton’s mind. Benton experienced a change of heart regarding slavery after 1849, and actually went on to oppose its spread in the territories recently won by the U.S. in the Mexican-American War. In the debates that occurred during the Great Compromise of 1850, Benton so fervently denounced slavery that he was almost shot on the senate floor by Henry S. Foote of Mississippi. Benton’s actions seem especially remarkable when one remembers that during this time of increasingly impassioned arguments regarding slavery, people tended to retrench their beliefs rather than reverse them.

Upon drafting his influential letter to Benton, Eliot jotted down a few private musings on the import of his cause. Open abolitionism was considered social anathema in St. Louis at the time, and Eliot’s letter was a step towards besmirching his public reputation and that of his family. As he mentioned in his notes, “There [I] pass by the Slave Jails on Olive St. without saying, aloud, more times quite aloud, may the cause of God abide upon this evil traffic! Yet I have spoken in public of it comparatively seldom.” Following this anecdote, he worried about his own moral rectitude, but then stated that he could more effectively end slavery in Missouri as a closeted abolitionist than as an open one.

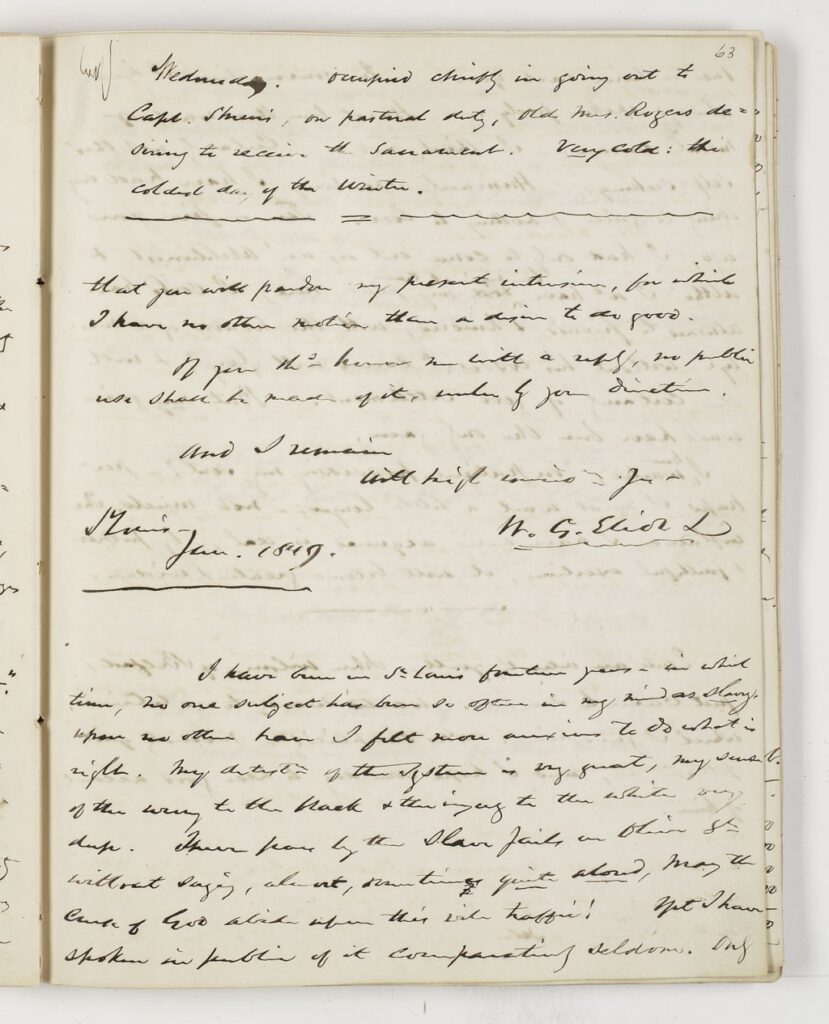

Here is an excerpt from Eliot’s notebooks:

I have been in St. Louis fourteen years, in which time, no one subject has been so often in my mind as slavery. Upon no other have I felt more anxious to do what is right. My detest[atio]n of the system is very great, my sense of this wrong to the black & this incg[?] to the white very deep. There pass by the Slave Jails on Olive St without saying, aloud, more times quite aloud, may the cause of God abide upon this evil traffic! Yet I have spoken in public of it comparatively seldom. Only once or twice each year. In conversation I have always spoken freely. – Has it been thro’ want of moral courage, _ I think not. Certainly not thro’ self-seeking. Humanly speaking I have had every thing to gain & nothing to lose. Ten or five years ago, I had only to come out as an “Abolitionist” & altho’ I w[oul]d have ^been required to leave my place here, I could have returned to friends & kindred, with the honors of a martyr, without his losses: “covered with glory”, & with the certainty of good settlement. But my gain would have been the only gain.

I have waited, “in patience possessing my soul”. – perhaps I must wait a little longer, – not much. The influence I have not acquired is real, – by proper and faithful exertions, it will become greater & wider.

William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers, Notebook 2, pgs. 63-64, September 1849-December 1852.

Please check back next month for another installment of “From the Desk of William Greenleaf Eliot.” In the meantime, you can consult the Archives’ William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers, as well as this library research guide. You can also see images of Eliot’s notebooks at the Missouri Digital Heritage site.

A big thank you to Ethan Bennett and Max Forrester, both Ph.D. students in American History at Washington University.

Sources

- William Greenleaf Eliot Personal Papers;

- Rev. Dr. Earl K. Holt III, William Greenleaf Eliot: Conservative Radical;

- Charlotte C. Eliot, “William Greenleaf Eliot,” in Heralds of a Liberal Faith, Vol. III.