Finding James Merrill in the Archive

Alex Mouw is a PhD candidate in the Department of English and a Lynne Cooper Harvey Fellow in the Program in American Culture Studies.

Thumbing through the personal documents of a bygone poet might sound like a fusty affair. But for lovers of literature, the nondescript boxes and manilla envelopes of library archives are nothing less than a treasure trove. Dedicated scholars, fellow writers, and fans can spend hours wading through handwritten letters, drafts, and personal paraphernalia from important authors and movements. Sometimes these explorers are looking for an annotation or a scribble that will unlock new literary insights, and sometimes they just want to see the handwriting of a treasured author.

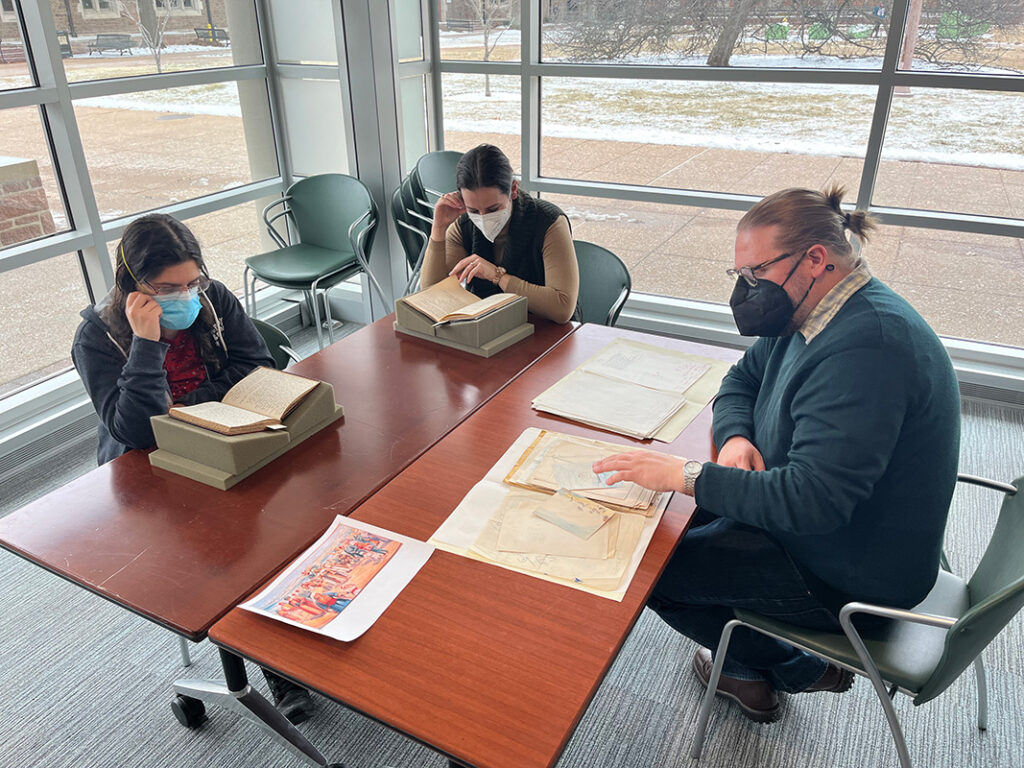

This semester the Poetry and Poetics Reading Group, a collection of faculty and graduate students sponsored by the Center for the Humanities, has taken a crash course in the archival experience. With the help of Joel Minor, curator of the Modern Literature Collection in the Julian Edison Department of Special Collections at Washington University Libraries, they have explored the papers of 20th-century poet James Merrill (1926-95), which he began donating to Washington University in 1964.

There’s much to investigate, for Merrill was prolific. The son of a Southern socialite and the investment banker Charles E. Merrill, James turned the freedom afforded by his wealth toward travel, letter-writing, and, most of all, poetry. He wrote over a dozen collections of verse, three novels, a memoir, and several plays, winning major awards including two National Book Awards along the way. The vast majority of his countless drafts, diaries, notebooks, and even financial statements reside at Olin Library and are open to anyone interested in them. Some of the materials are even available online, for example in The James Merrill Digital Archive, an ongoing project of Washington University’s Humanities Digital Workshop.

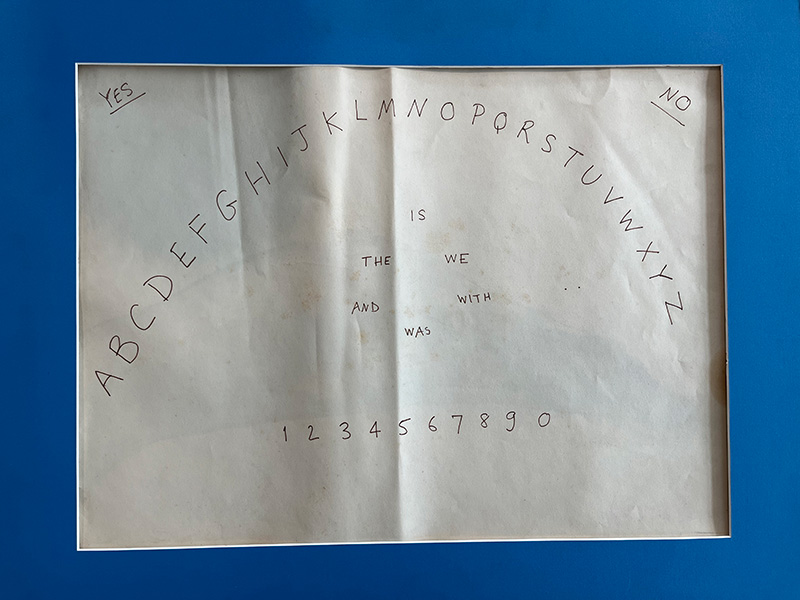

Among the gems that the Poetry and Poetics Reading Group inspected this semester was the Ouija board used by Merrill and David Jackson, his longtime partner. After a friend gave Merrill the spiritualist communication device as a gag in 1953, he and Jackson spent whole nights at the board. They transcribed their “conversations” with literary heroes and friends they had mourned, ostensibly guided by a first-century spirit named Ephraim. Merrill sculpted decades of transcribed Ouija sessions into a 90-page epic poem titled “The Book of Ephraim” (1976). In it, the spiritual trio of Merrill, Jackson and Ephraim reflect on their pasts, learn about the afterlife and gossip. Dictated by the zany movements of a teacup on an alphabet, it’s a surprisingly fun masterpiece of modern American poetry.

Having seen the Ouija board and read the poetry it prompted, reading group member Ann Marie Jakubowski, a graduate student in the Department of English, took a further inquiring step. Her hunch was that Merrill’s visionary poem might be indebted to an earlier poet: T.S. Eliot. She hunted down Merrill’s personal copy of Eliot’s own ecstatic work Four Quartets (1943) and found that the pages were covered with Merrill’s annotations, promising new knowledge about both poets.

As a member of the group myself, I took another tack from the Ouija board, this time toward the person who originally gave it to Merrill: Frederick Buechner. A Presbyterian minister and novelist, Buechner became Merrill’s close friend in high school, and they corresponded throughout their lives. Theirs was an unexpected friendship, given Merrill’s lack of conventional piety and the strictures against homosexuality in Buechner’s denomination. The relationship represented in their letters offers fresh angles on the lives of two artists, as well as changes in American life and literature after World War II.

Such pursuits may end up joining a recent surge in Merrill scholarship. A 2015 Merrill biography, a study of poetry and queer gossip, and an analysis of the doodles Merrill often added to the margins of his poem drafts have all enriched our understanding of this essential poet, and none would be possible without the archive. As Washington University scholars, members of the Poetry and Poetics Reading Group hope to channel their own archival experiences into peer-reviewed articles, dissertation chapters, and even poems of their own. Although it is possible to study and appreciate Merrill without actually holding his diaries, photo albums, and drafts, the immersive archival experience is far more rewarding.

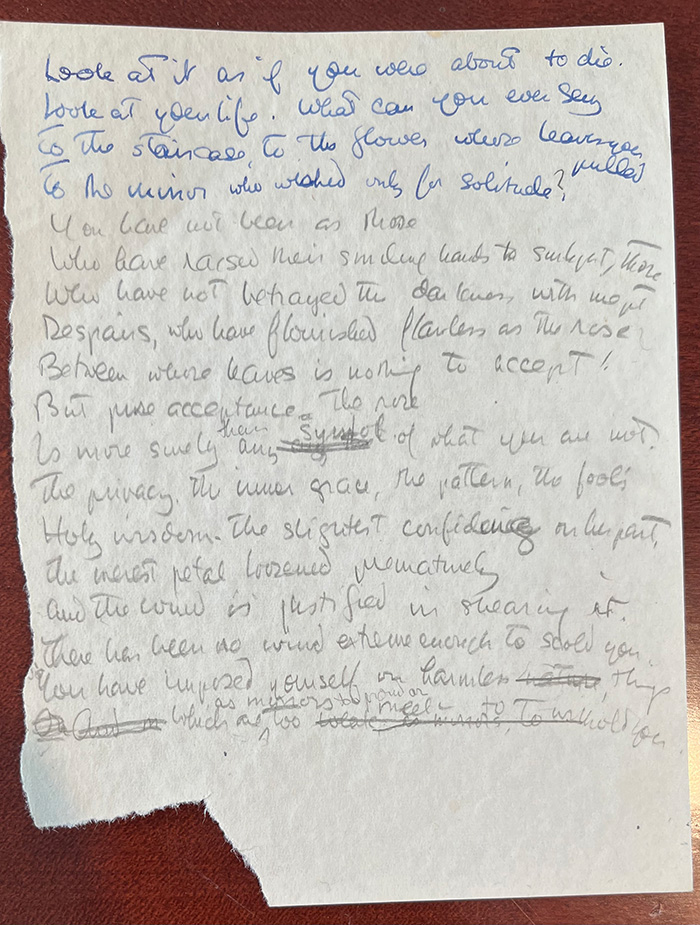

Near the end of a recent meeting, group member Philip Purchase, a senior lecturer in the Interdisciplinary Project in the Humanities, read entries from a personal diary that Merrill kept during college. As he thumbed through the pages of elementary French, romantic tidbits, and family troubles, a small, ripped piece of paper fell from between the rear flyleaves. It featured lines of verse found nowhere in Merrill’s published works.

“I don’t think anyone has ever seen this before,” said Minor, the archive curator. Tucked in the back of an already juicy diary, it had sat in Olin for decades, waiting.

“There’s still lots here to keep us busy,” replied Purchase.

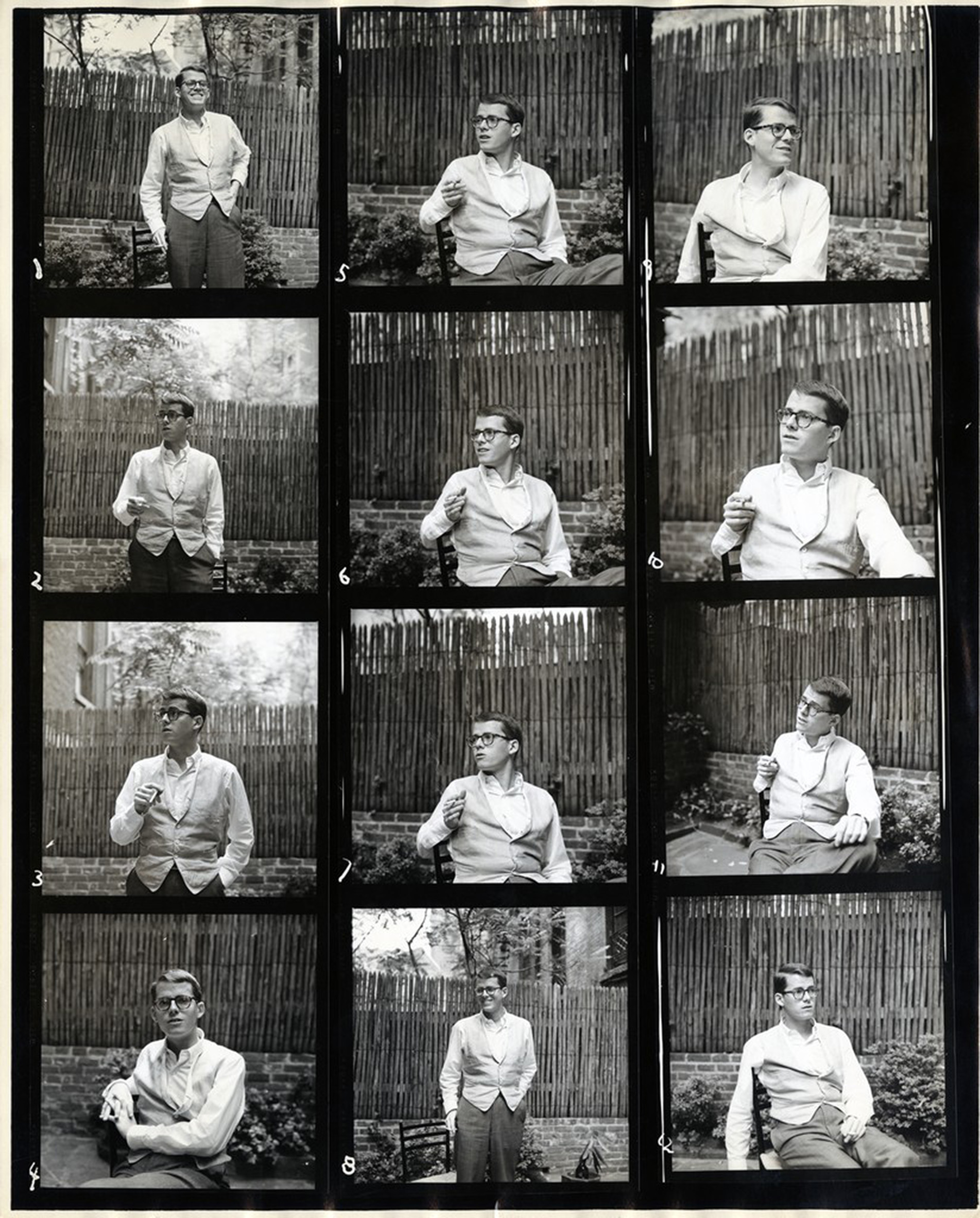

Feature image: Contact sheet of portraits by Rollie McKenna of James Merrill as a young man, sitting outside smoking a cigarette. Courtesy Modern Literature Collection at WashU Libraries.

The article originally appeared on the Center for the Humanities website and is republished here with the author’s permission.