Early Modern Pragmatism: Medieval Manuscripts as Binding Material

Medieval manuscripts are handwritten documents dating from roughly 500 to 1500 CE and were primarily written on parchment, also called vellum. While viewed as precious today, medieval manuscripts were routinely cut up and recycled for various purposes including use in book bindings. This practice reflects an economical approach to resources which stressed repairing, recycling, and repurposing materials.

With the wide adoption of the printing press in the West, beginning around 1450, paper rapidly replaced parchment for text because it worked better for printing. Nevertheless, parchment remained in favor for use in book structures because, while it is flexible and easy to cut, it is also very strong and highly resistant to tearing. Parchment was (and is) expensive. It is crafted from animal skin through a meticulous, time- and labor-intensive process. The result is a material ideal for creating sturdy book bindings.

Repurposing old texts was a practical approach to conserving costs and valuable raw materials. Damaged and outdated manuscripts were all candidates for use as ‘binding waste’. Today fragmentology—the multidisciplinary study of manuscript fragments – is a growing area of research spurred on by digital imaging. Even the smallest scraps in a book may tell scholars where a book was bound or uncover rare scripts and texts. Fragmentologists have even been able to digitally reassemble entire texts.

Scholars estimate one in five bindings from between 1450-1600 CE contain medieval manuscript fragments. WashU’s Rare Books Collection holds thousands of books from the early modern period. Many have traces of medieval texts hidden within – and sometimes right on the cover!

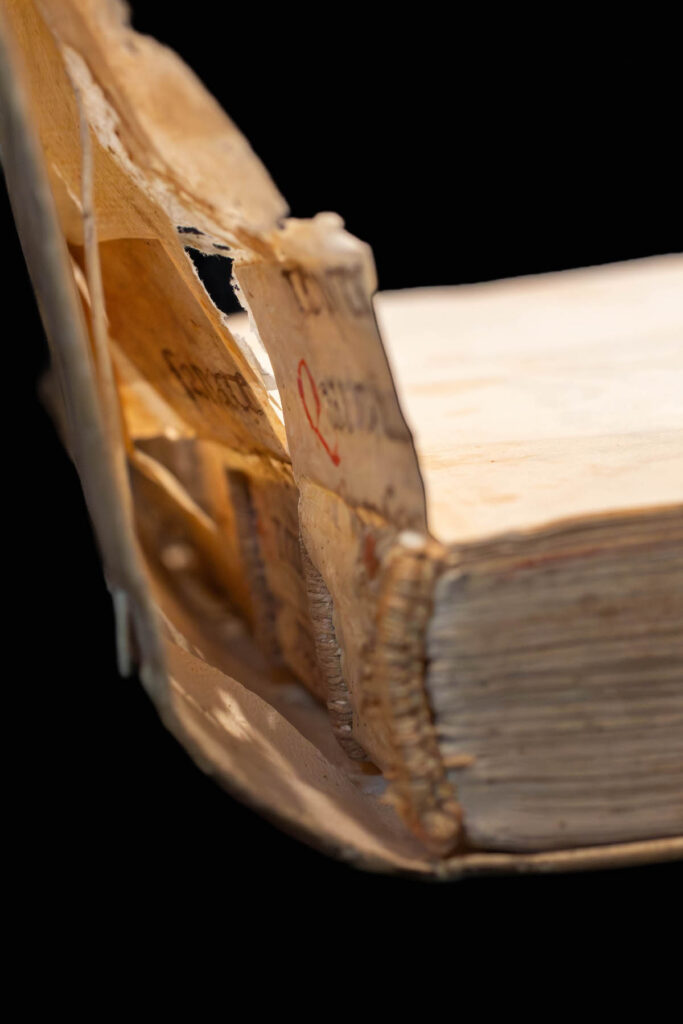

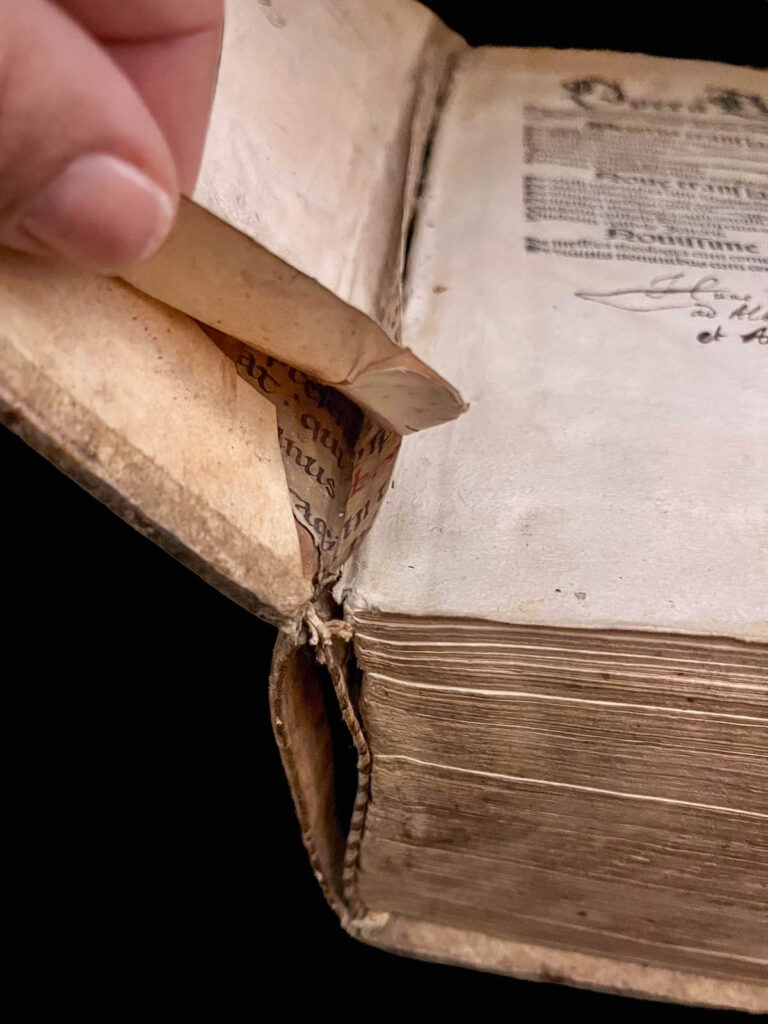

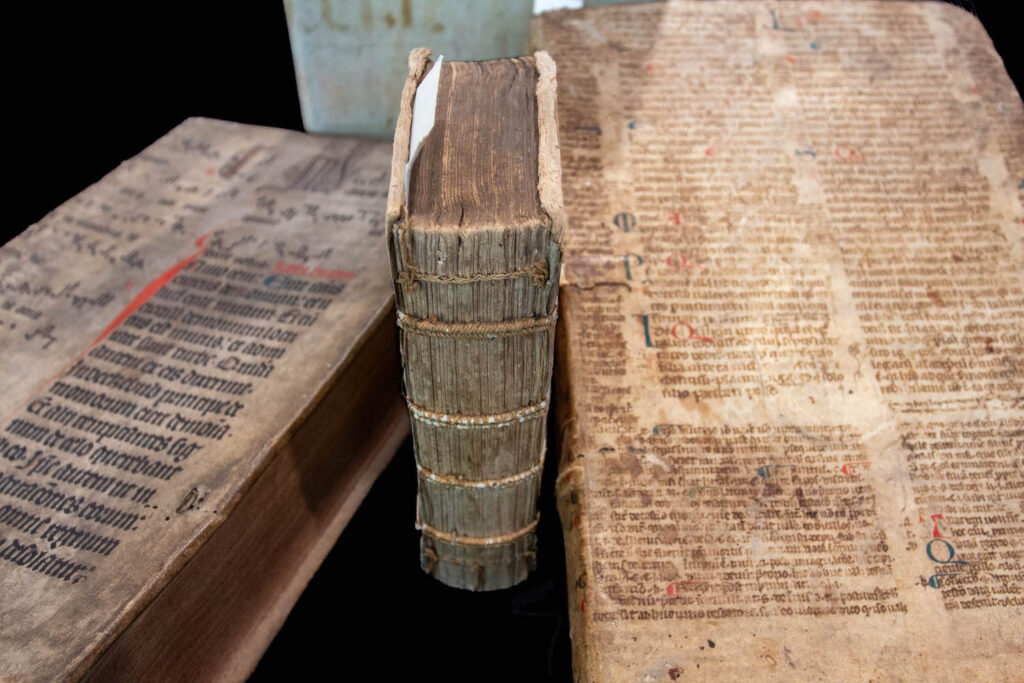

Sewing Guards and Reinforcing Tape

Small strips of vellum were often used to protect signatures (i.e. sections of folded pages) when sewing or to support the spine and reinforce the text block’s attachment to the boards.

Some fragments are so small or well hidden within the binding that they are only barely visible. Fragmentologists use a variety of techniques such as multi-spectral imaging, x-rays, and 3D mapping to reveal what’s hidden within.

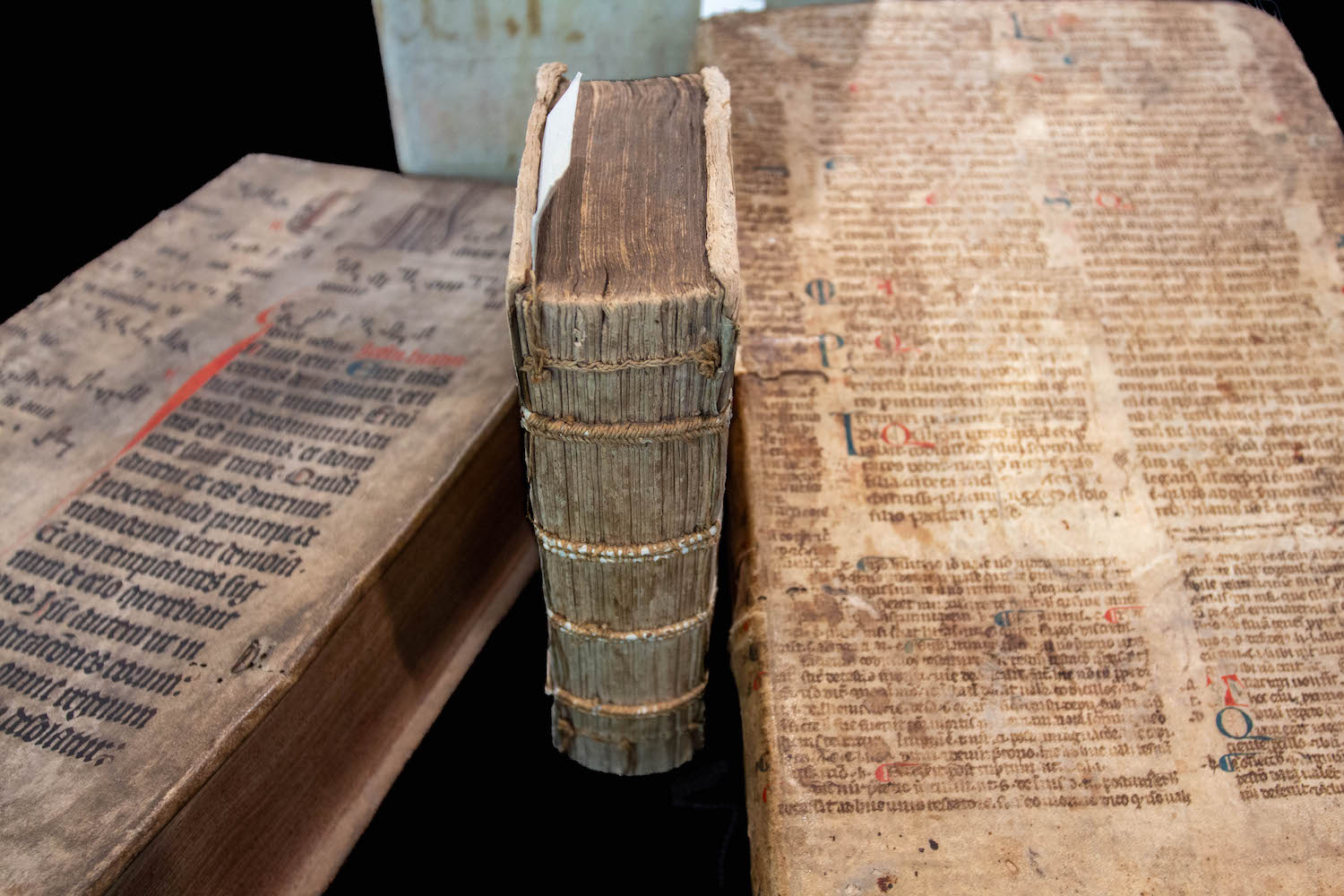

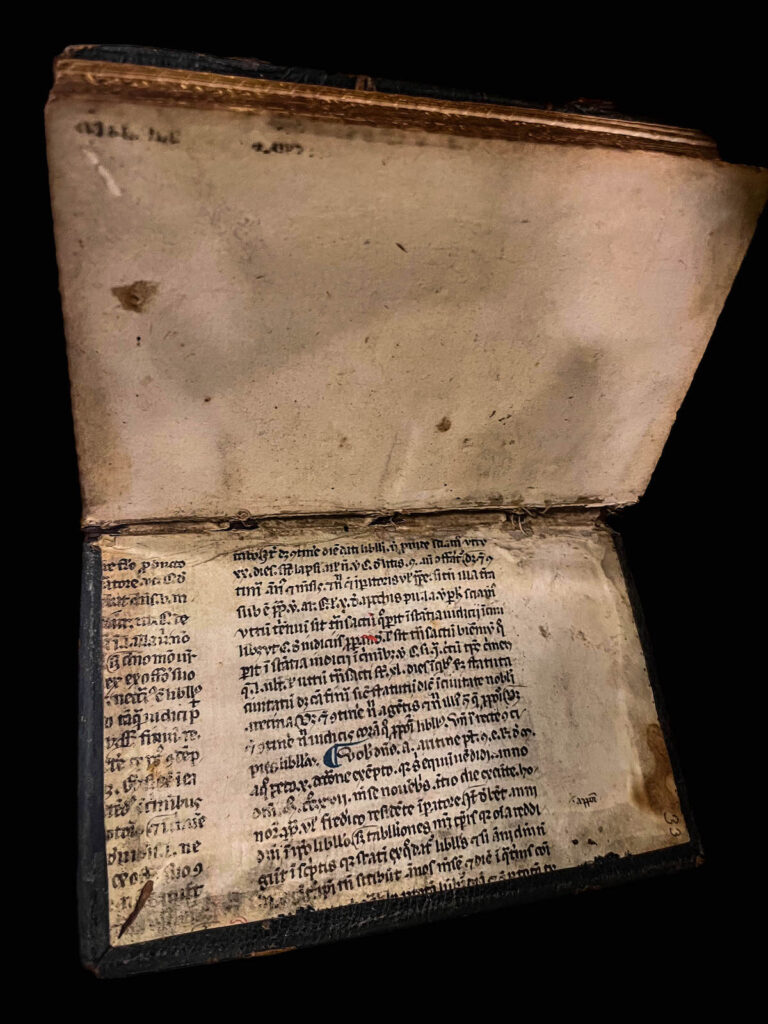

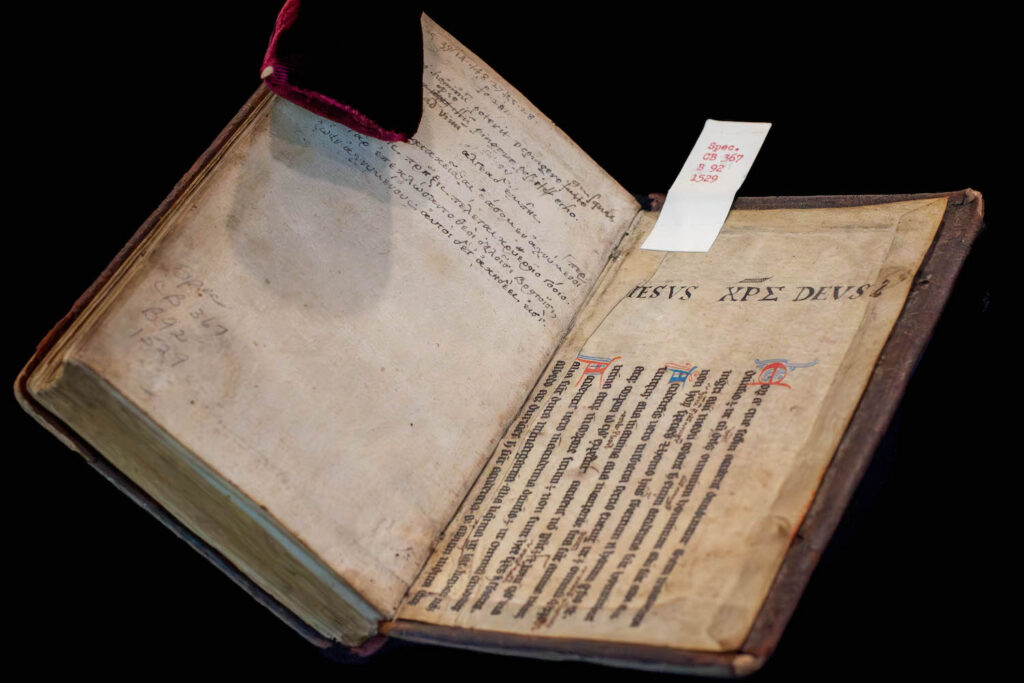

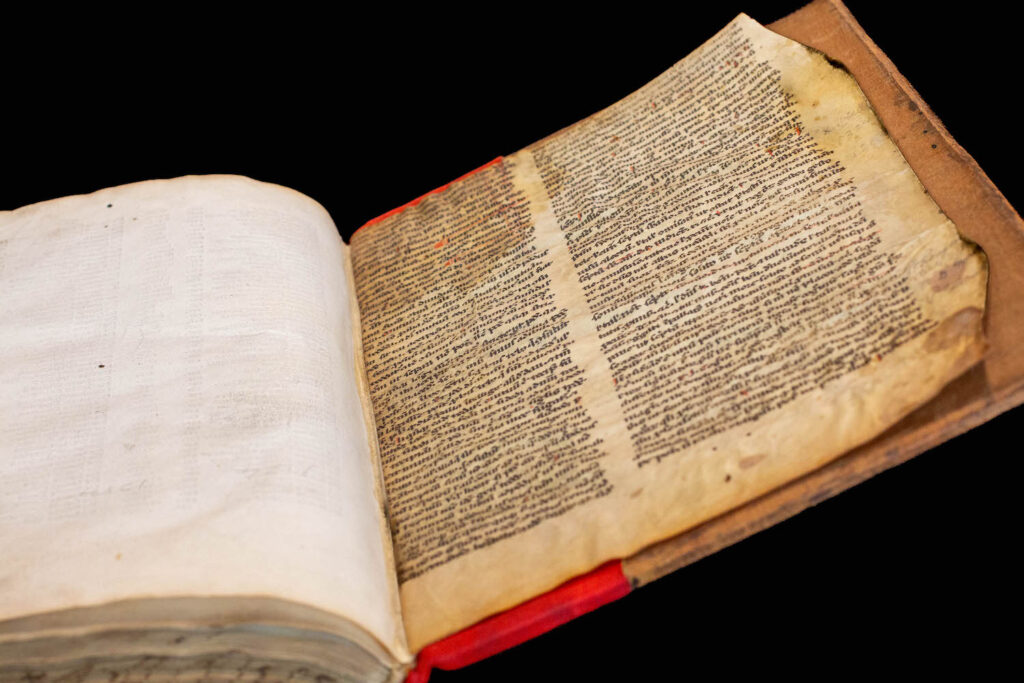

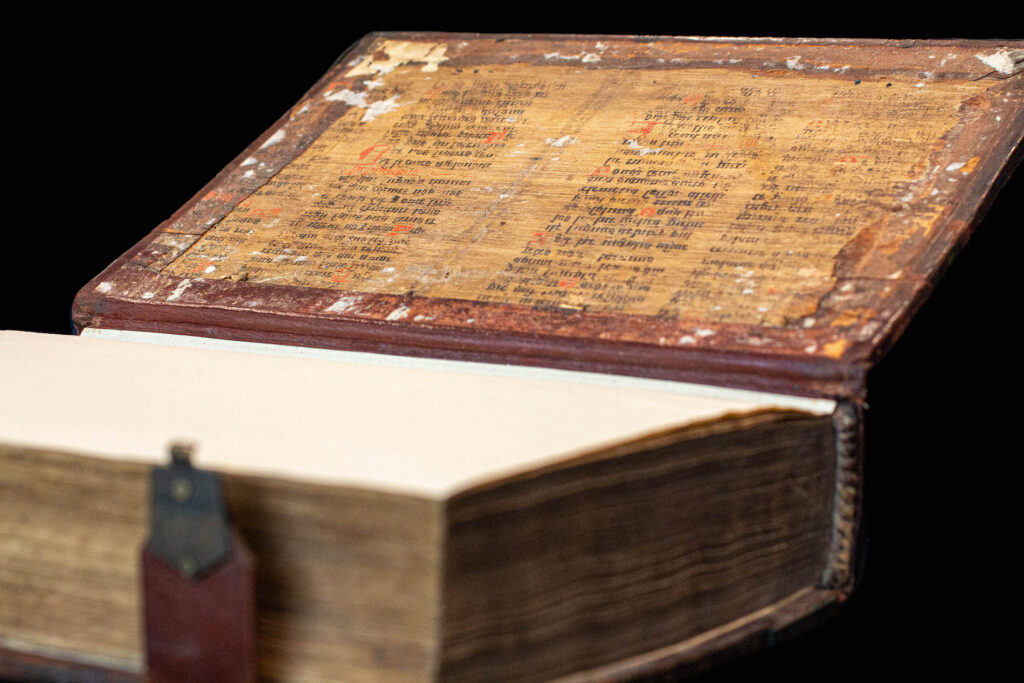

Pastedowns and Flyleaves

More substantial manuscript waste may be found on the inside front and back covers of a book as pastedowns (a leaf glued to the inside cover) and flyleaves (leaves that come before and after the text block). Pastedowns and flyleaves protect the text block from rubbing on the binding, hide sewing cords, and support the book structure.

Some pastedowns and flyleaves can be quite large, such as in the two books above which are both around 13 inches tall. The book on the left shows only an offset of a manuscript waste pastedown which is no longer with the volume, but legible enough to be of use to scholars.

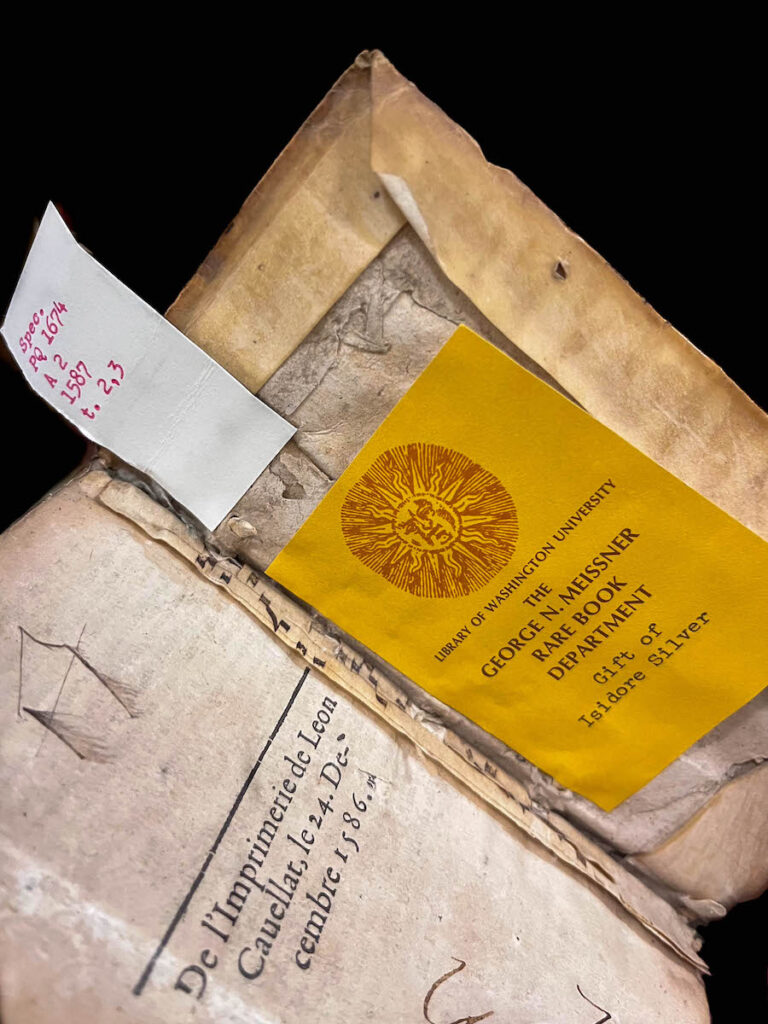

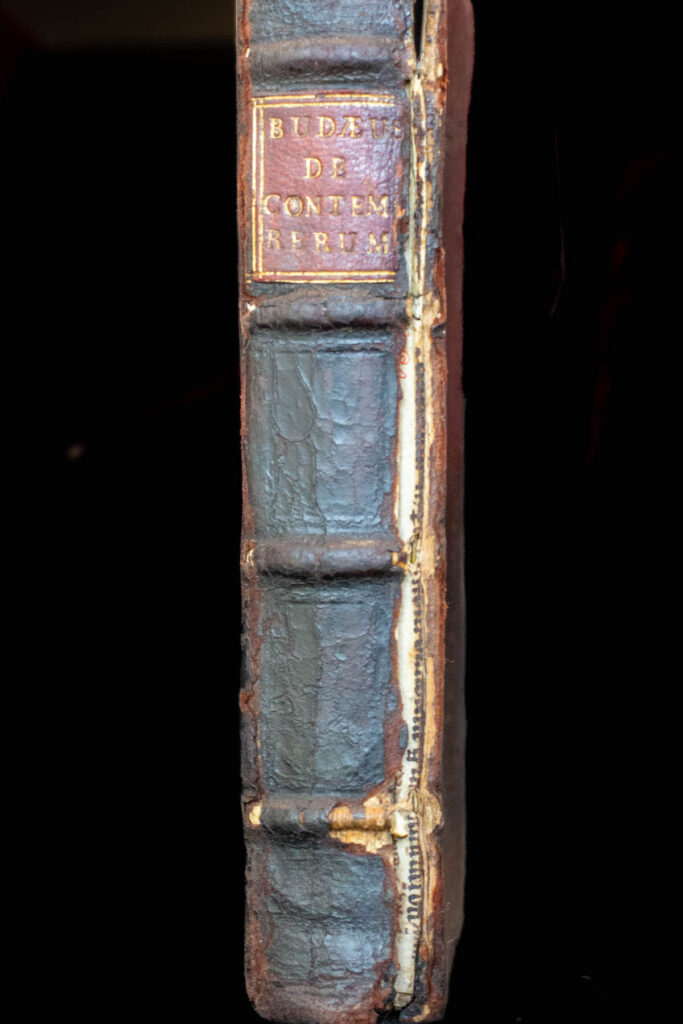

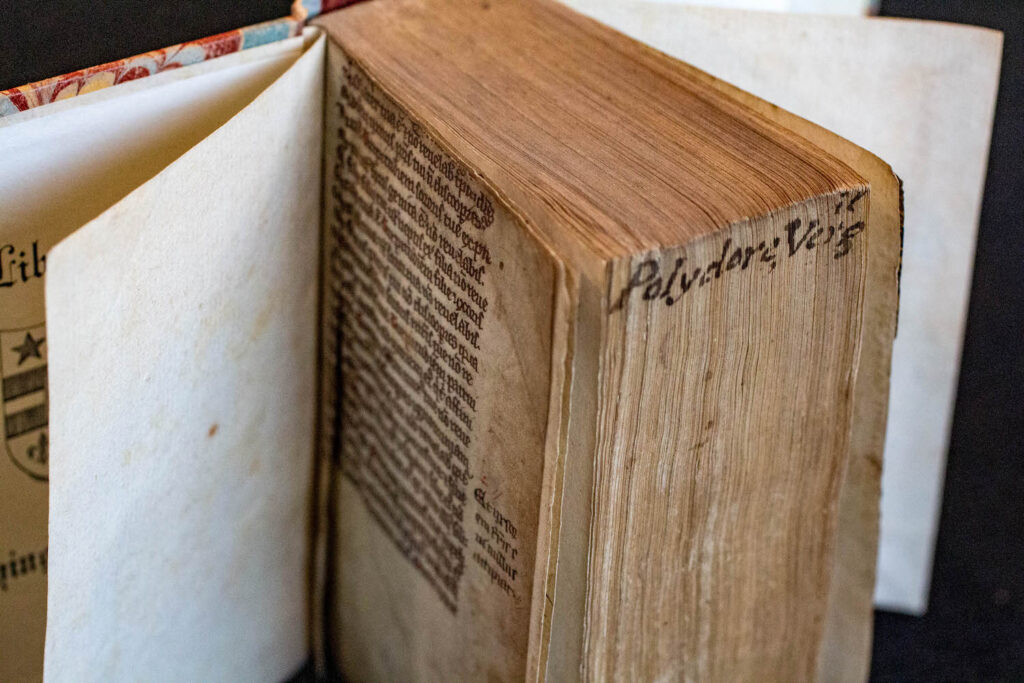

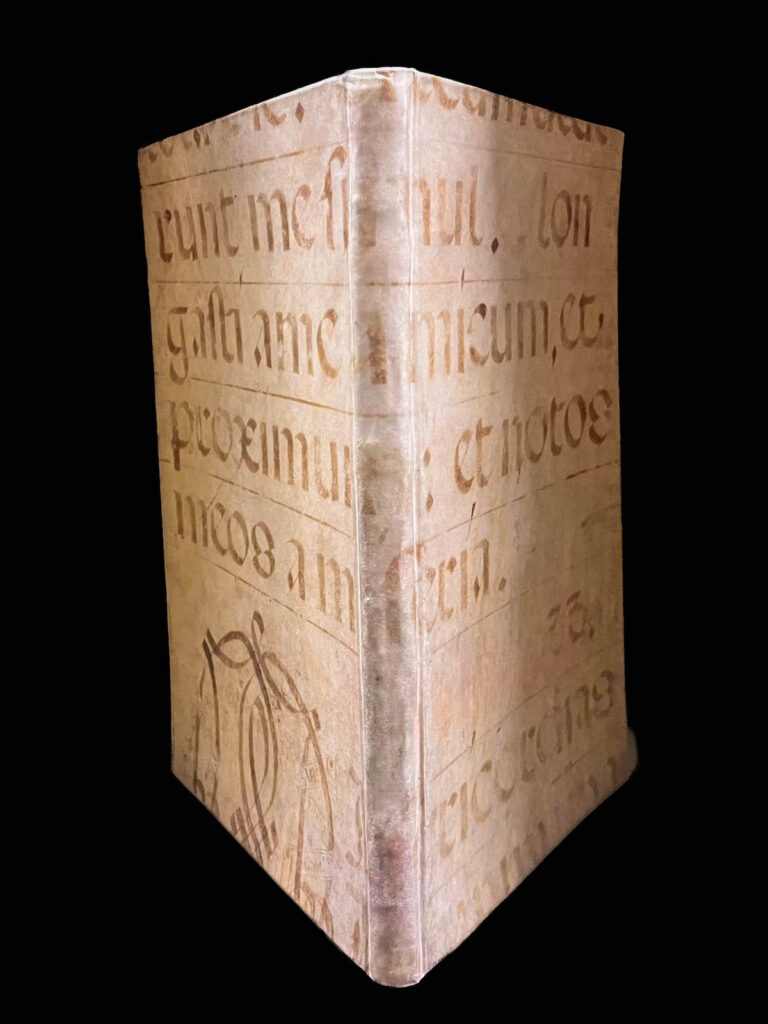

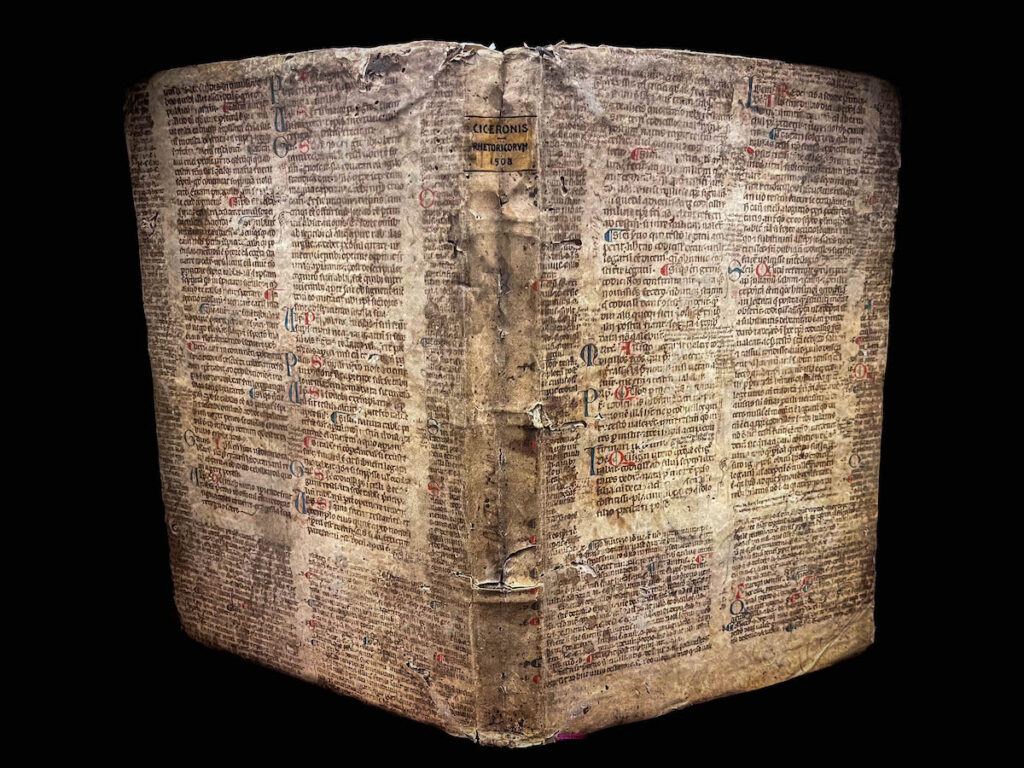

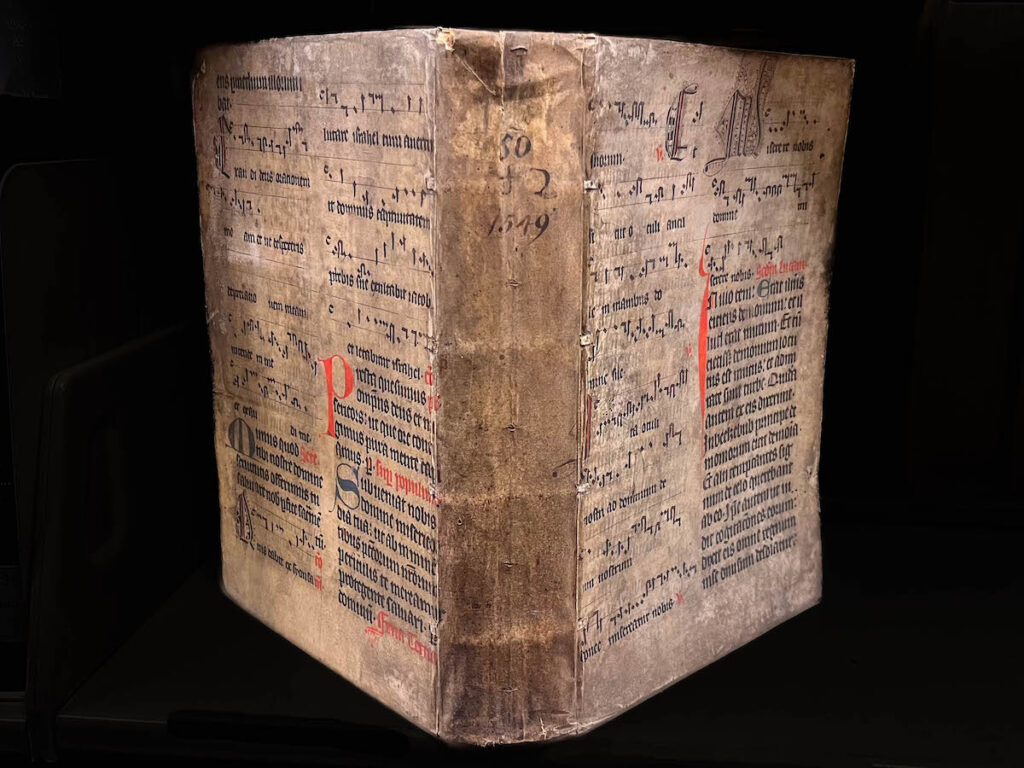

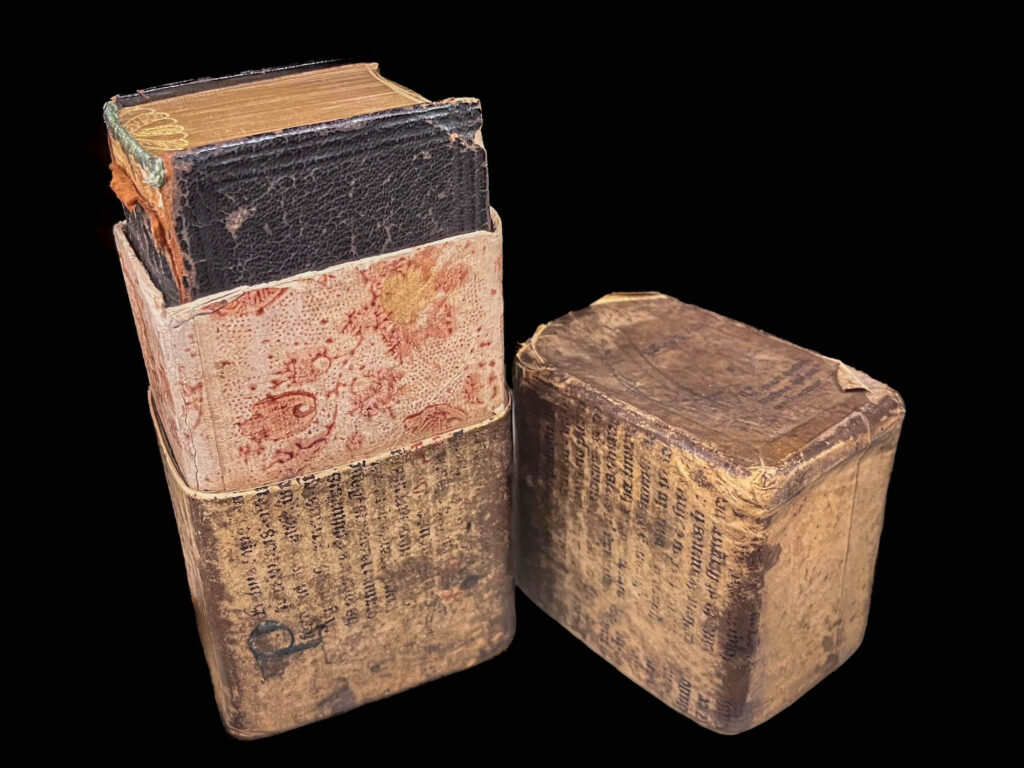

Wrappers

The largest binding fragments are generally found as bifolium (two connected leaves) reused as a wrapper (cover). While today these covers may seem special and interesting, they have much more humble origins. Until the 1800s, texts came unbound or with a simple binding. Consumers could pay extra for a wrapper of their choosing. A wealthy person might have each binding in their library match, but for the economical scholar using medieval manuscript waste was a practical solution. They benefited from the unparalleled qualities a parchment binding affords without the cost of buying something new.

Today books with medieval manuscript wrappers are stored in custom-made boxes to protect the images and text, but not too long ago someone used manuscript waste to create a pull-off box to fit a printed book. The box perfectly houses a small 1726 Luther Bible.

There are undoubtedly more manuscript fragments to be found within WashU’s Rare Book Collection and more discoveries to be made about where they came from and what knowledge they contain. Meanwhile, simply their presence is a testament to a bygone worldview that valued salvaging resources to cut down on the consumption of raw materials.

For more information, please contact Cassie Brand, curator of rare books.

Further Reading

Bamford, Heather. Cultures of the Fragment: Uses of the Iberian Manuscript,1100-1600. Toronto ; Buffalo: University of Toronto Press, 2018.

“Fragmentarium.” Laboratory for Medieval Manuscript Fragments, July 11, 2019.

Mullett, Ruth. “In Situ Manuscript Fragments in the Incunables of the Bodleian Library, Oxford: A Fragmentarium Case Study.” Fragmentology, no. 1 (December 10, 2018).

Treharne, Elaine. Perceptions of Medieval Manuscripts: The Phenomenal Book. First edition. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Wellesley, Mary. The Gilded Page: The Secret Lives of Medieval Manuscripts. New York: Basic Books, 2021.

Christa Kileff is a graduate student in library and information science at the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign. She recently completed a practicum in the Special Collections Department supervised by Cassie Brand.