Discovering a 17th Century “Yearbook”

As commencement approaches, many of our graduating seniors will soon be circulating their yearbooks, filling them with the signatures of their departing friends and colleagues. This practice of signing books is a college tradition that dates back as far as the 1540s, when students in Wittenberg, Germany, began collecting the signatures of their professors.

While students today collect signatures in yearbooks created specifically for their universities, these German students did not have such a luxury and generally circulated Bibles and other classic books for their friends to sign. The earliest examples of these books contain signatures alongside classic quotes from authors like Ovid, Cicero, Augustine, and Seneca. Within a few decades, the practice had became so popular that publishers began publishing books with interleaving blank pages specifically for collecting signatures.

Using Emblem Books as Autograph Books

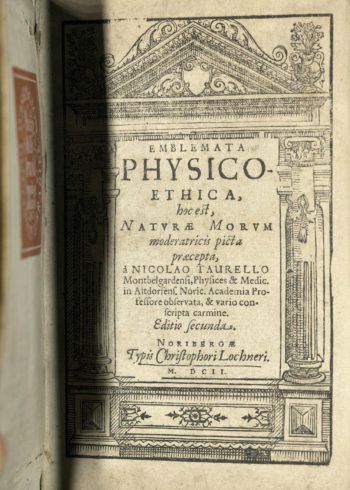

As the tradition of signing books continued in Germany and other European countries, Andrea Alciati’s Emblematum became a particularly popular book in which to collect signatures. The Emblematum is a book of allegorical illustrations with accompanying mottos and/or explanatory text. It first appeared in Germany in 1531 and became so popular among Europeans that it created an entire genre of what are now known as “emblem books.”

One of these emblem books was the Emblemata Physico-Ethica written by Nicolaus Taurellus and published in Nuremberg, Germany in 1602. The Washington University Libraries own a very unique copy of this book that was used by a college student to gather the signatures of his peers in the early 17th century.

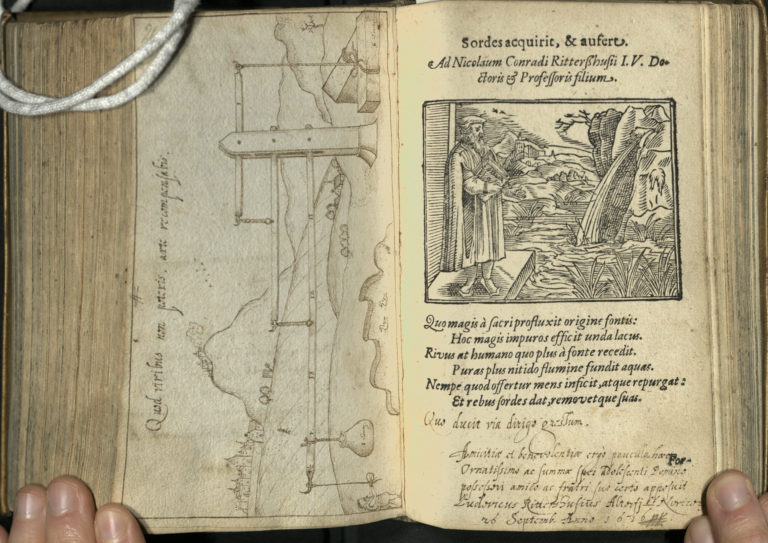

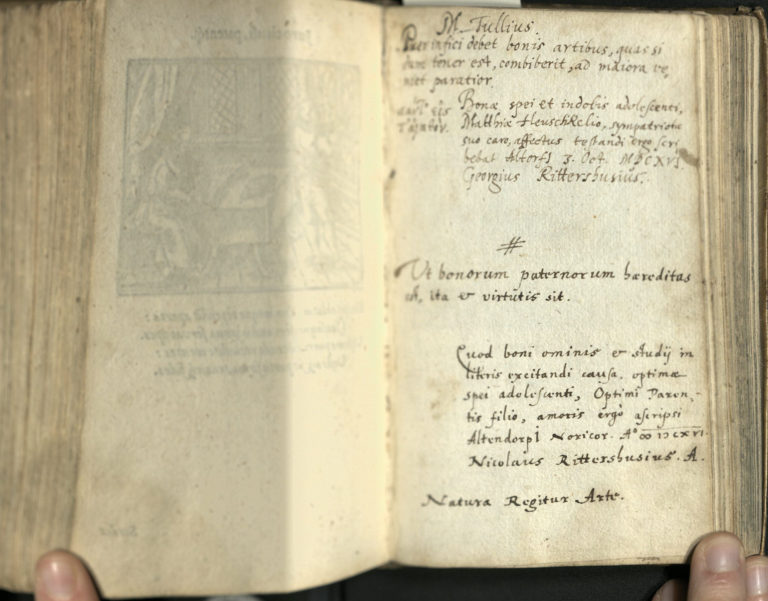

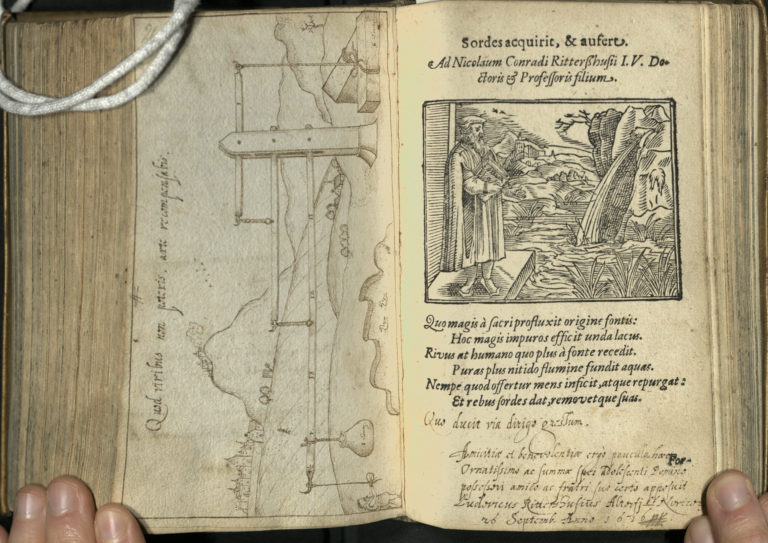

This particular copy of Physico- Ethica was owned by Matthias Heuschkel, a student at Altdorf University in 1616. It was likely purchased without a cover (a common practice in the Early Modern period) and later bound together with blank pages interleaved at irregular intervals, likely with the specific intention of using them as signature pages. Although most of these pages remain blank, four of them are inscribed in Latin by six of Heuschkel’s colleagues, some of whom have included hand-drawn emblems of their own.

The photos above show classmates’ hand-drawn emblems alongside the printed emblems of the text. As you can see, the drawings are very elaborate and blend well with the rest of the book. Because of this, the four pages of inscriptions were missed when Washington University first acquired the book and were not included in the catalog record. They were only recently discovered when the book was being used for a class, and a professor, noticing the blank pages, flipped through and found one of the hand-drawn emblems. Although emblems tend to be highly idiomatic and impossible to interpret with 100% accuracy, the scale instruments used in all three of the drawings suggest a theme of justice or virtue.

More Discoveries Are Waiting in the Archives

The discovery of these inscriptions goes to show that you never know what you are going to find in an Early Modern book. It is practically impossible for librarians to look through every page of every book they receive, and researchers can sometimes find things that catalogers have missed. These beautiful inscriptions, found by chance by a curious patron, give us hidden glimpses into the life of someone who owned this book over four centuries ago. What might you discover in Special Collections?