David Wagoner, 1926-2021

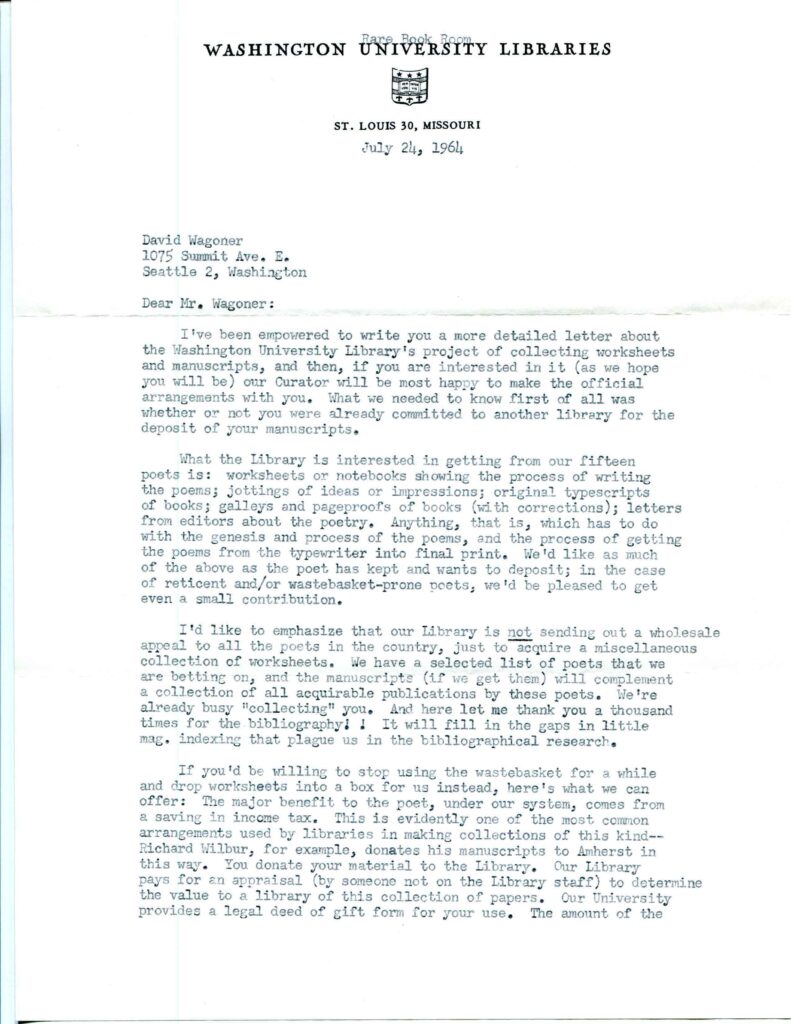

Last December we lost poet David Wagoner, whose literary papers were among the Modern Literature Collection’s earliest and most recent acquisitions. Wagoner first sent papers to Washington University in 1965, and in effect completed the collection by sending his remaining papers in 2012, resulting in 188 boxes—one of the largest manuscript collections we have.

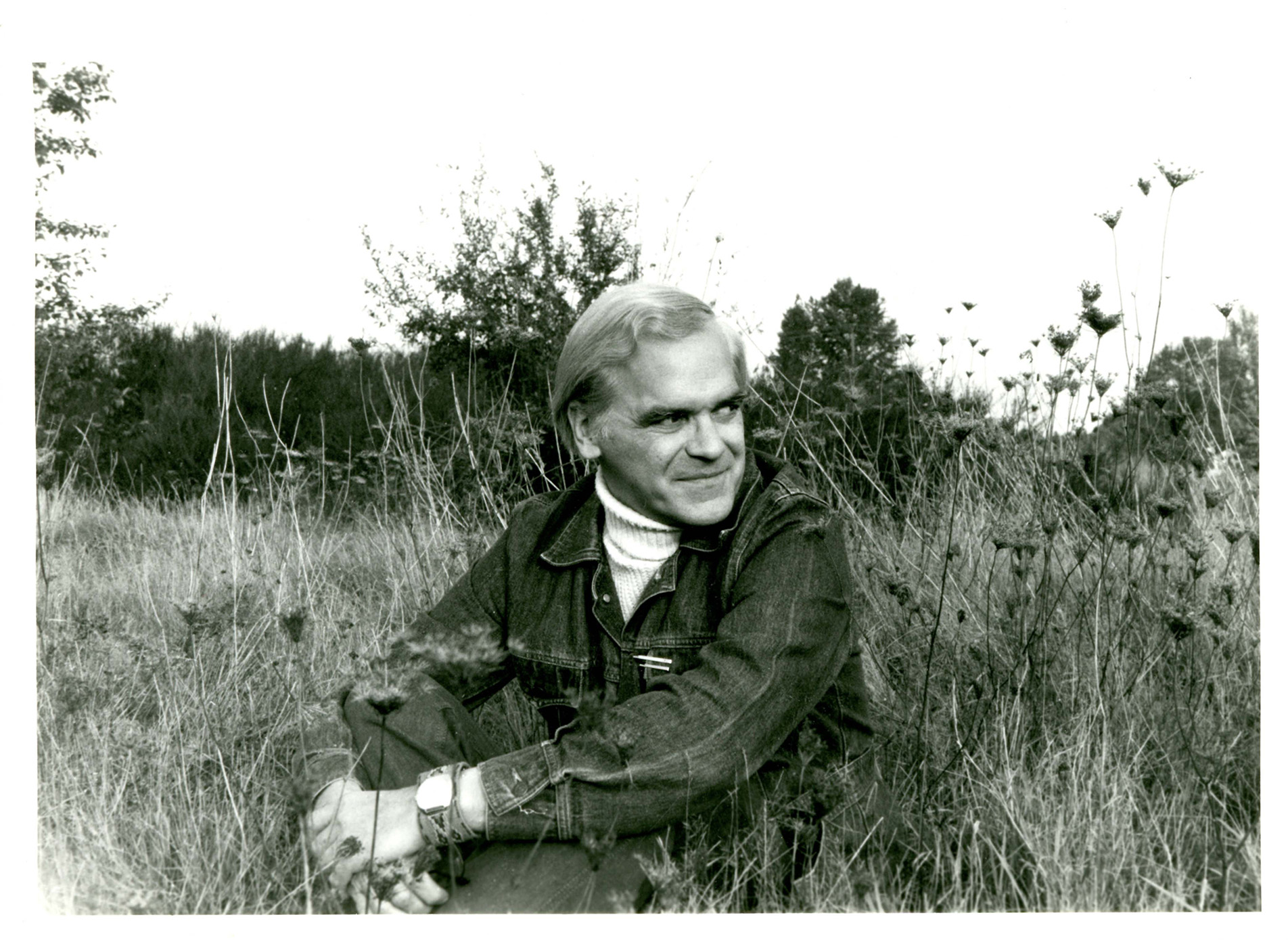

Although also a successful novelist (and short fiction writer and playwright), Wagoner gained most acclaim as a poet. In honor of National Poetry Month (and Earth Day—for Wagoner was predominantly a poet of the natural world ), we’re focusing our tribute on Wagoner’s accomplishments and contributions to poetry.

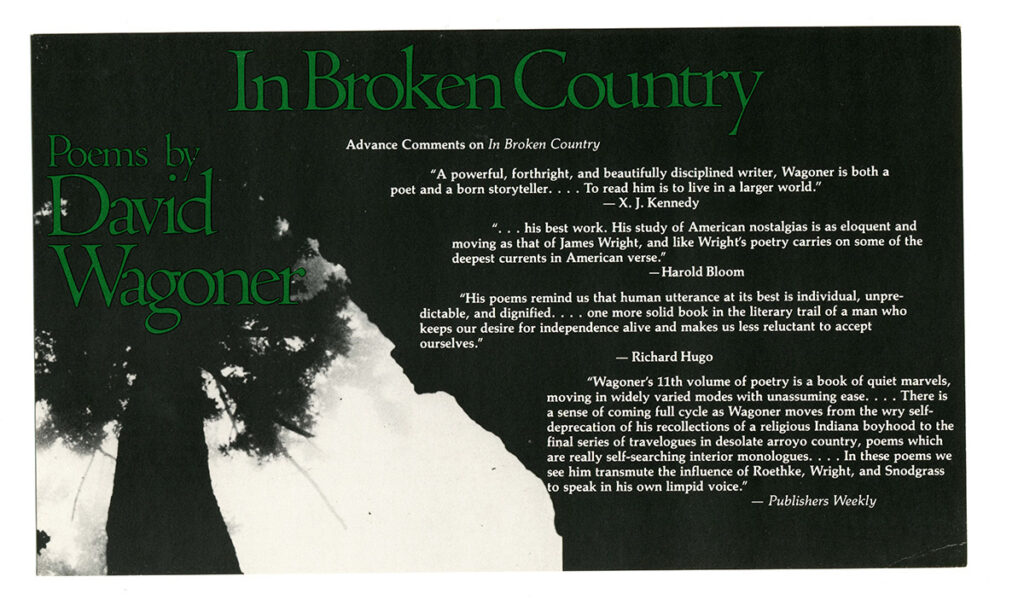

Wagoner published twenty poetry volumes and won numerous prizes and fellowships for his verse, including the prestigious Ruth Lilly Prize in 1991. He grew up mainly in Whiting, Indiana, and started writing poetry at a very young age, though he wasn’t certain of his path as a poet and a college professor until he took a poetry workshop with Theodore Roethke, as an undergraduate at Penn State University.

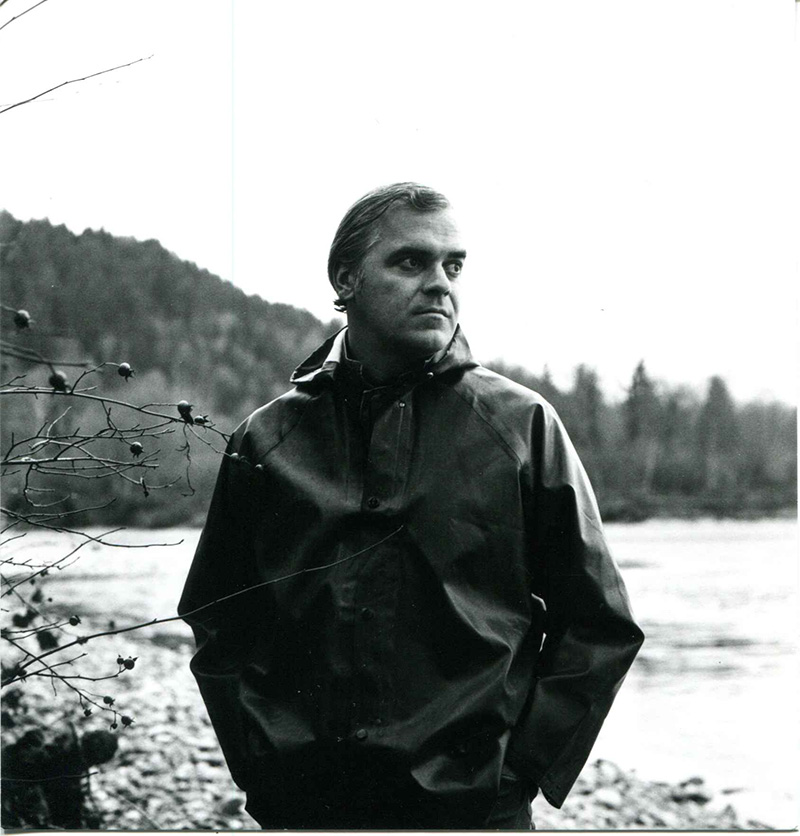

Wagoner’s poetic sensibilities were forever changed first by Roethke’s tutelage and then by his invitation to take an instructor position at the University of Washington, in 1954. Wagoner was a promising young poet and educator by this time, but he would soon make his lasting mark as a writer, teacher, and editor of poetry in the Pacific Northwest.

Wagoner spent most (forty-seven years) of his long career as a professor of poetry at the University of Washington. In addition, he was appointed to visiting professorships and temporary teaching assignments at various universities and conferences. After retirement, he remained active in teaching, most notably in the low-residency MFA program of the Northwest Institute of Literary Arts on Whidbey Island, and at the Richard Hugo House in Seattle.

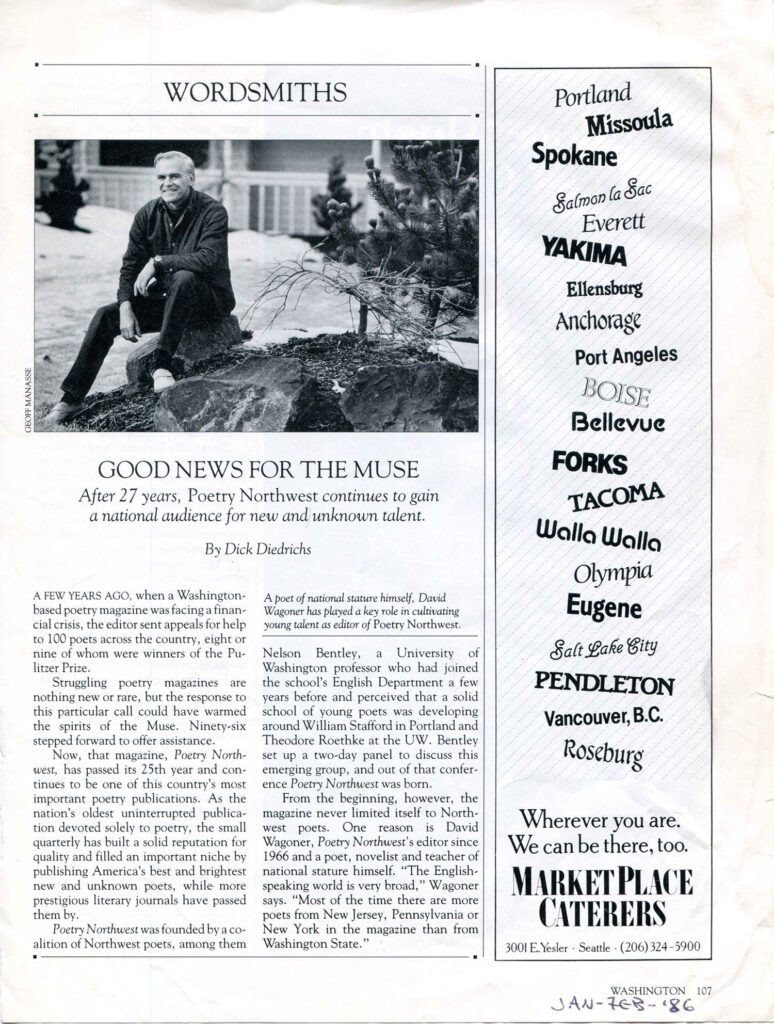

A major aspect of Wagoner’s impact on the world of poetry in the late twentieth century was as editor of Poetry Northwest, from 1966 to 2002. By then the publication was one of the oldest poetry-only magazines in the country but had to discontinue after Wagoner retired and it lost funding from the University of Washington (it was revived in 2005 and continues publication at the Attic Writers’ Workshop in Portland, Oregon).

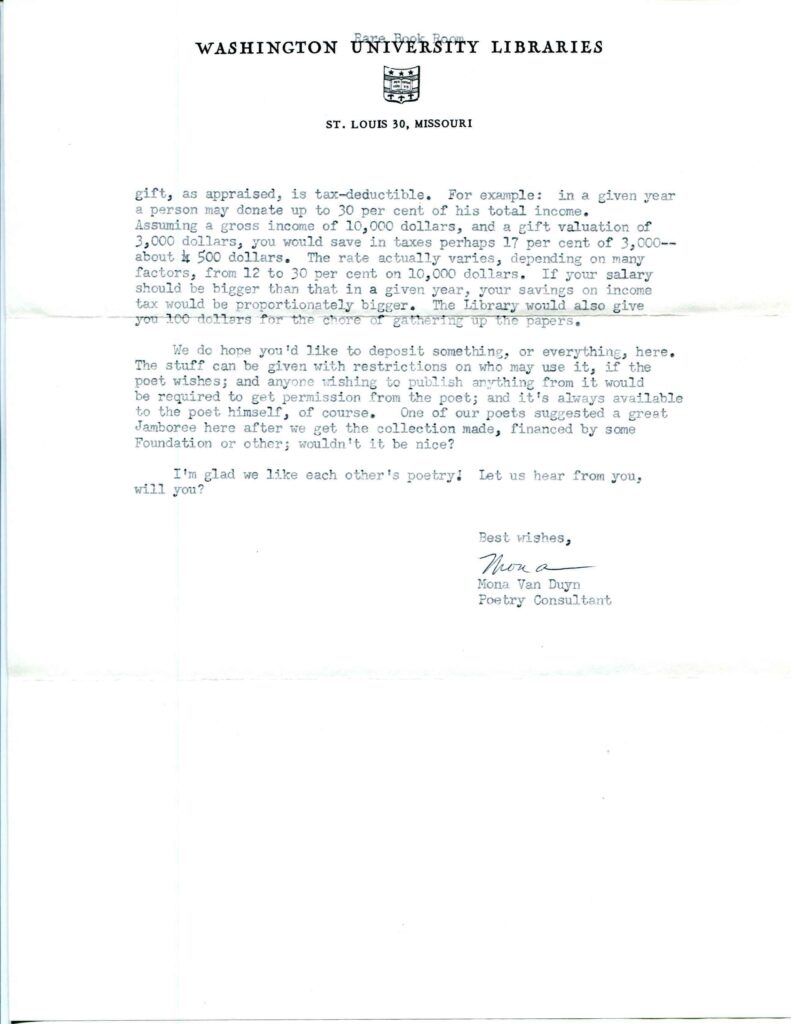

As such, the David Wagoner Papers contain a copious amount of submissions and correspondence from poets of the era (way too many to name here), as well as documents pertaining to periodic campaigns for fundraising, cover artwork, and more.

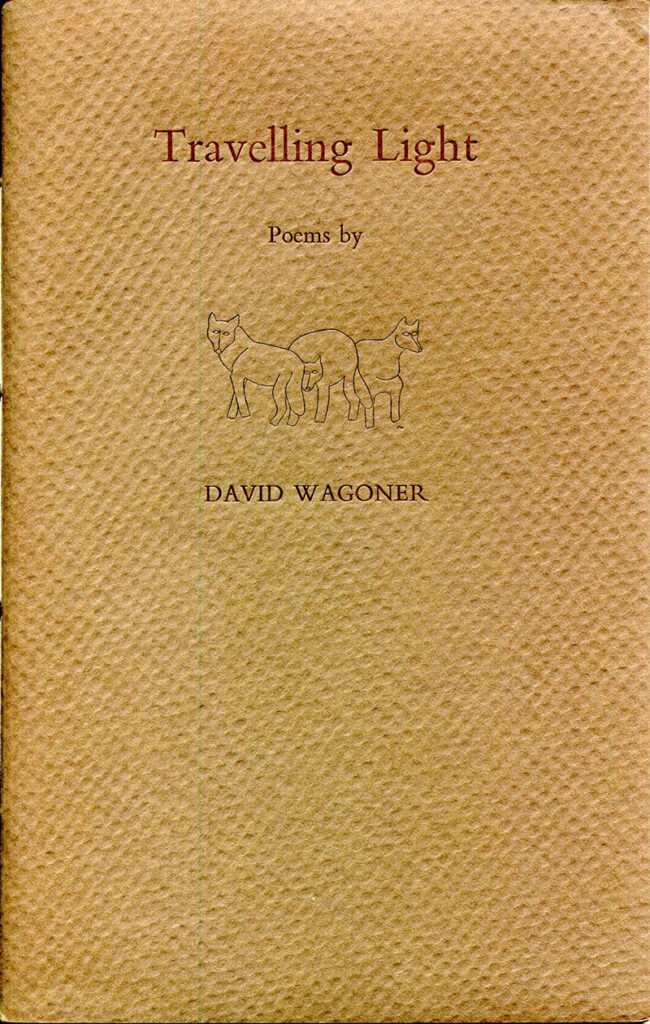

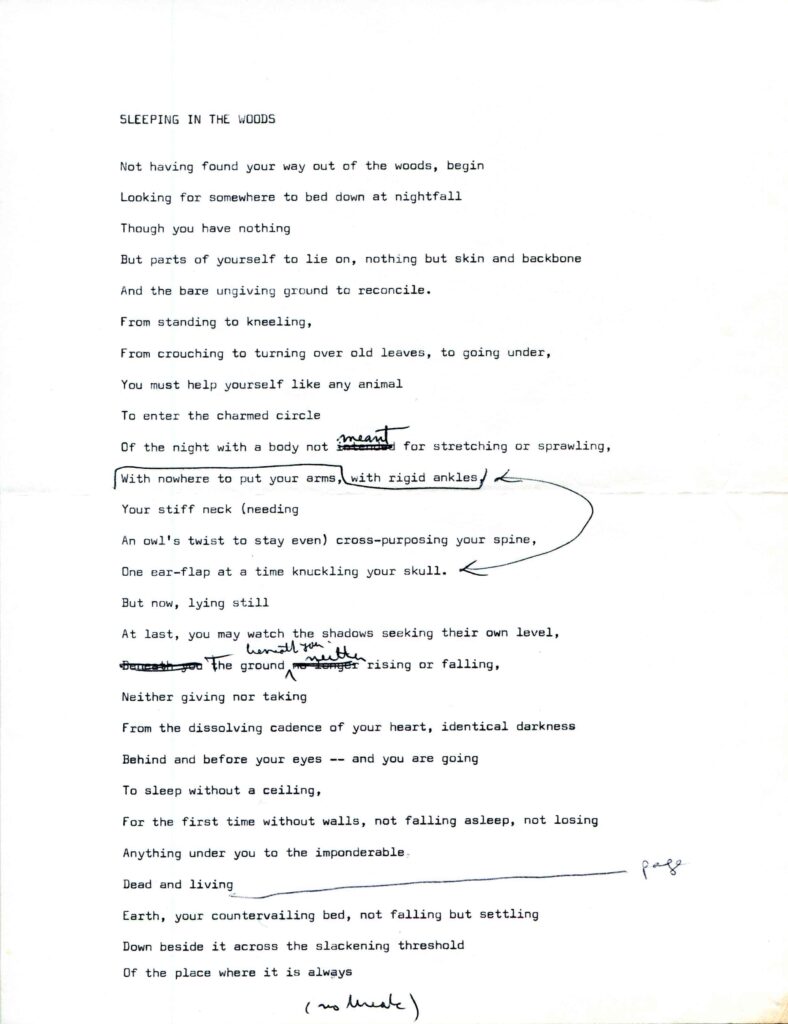

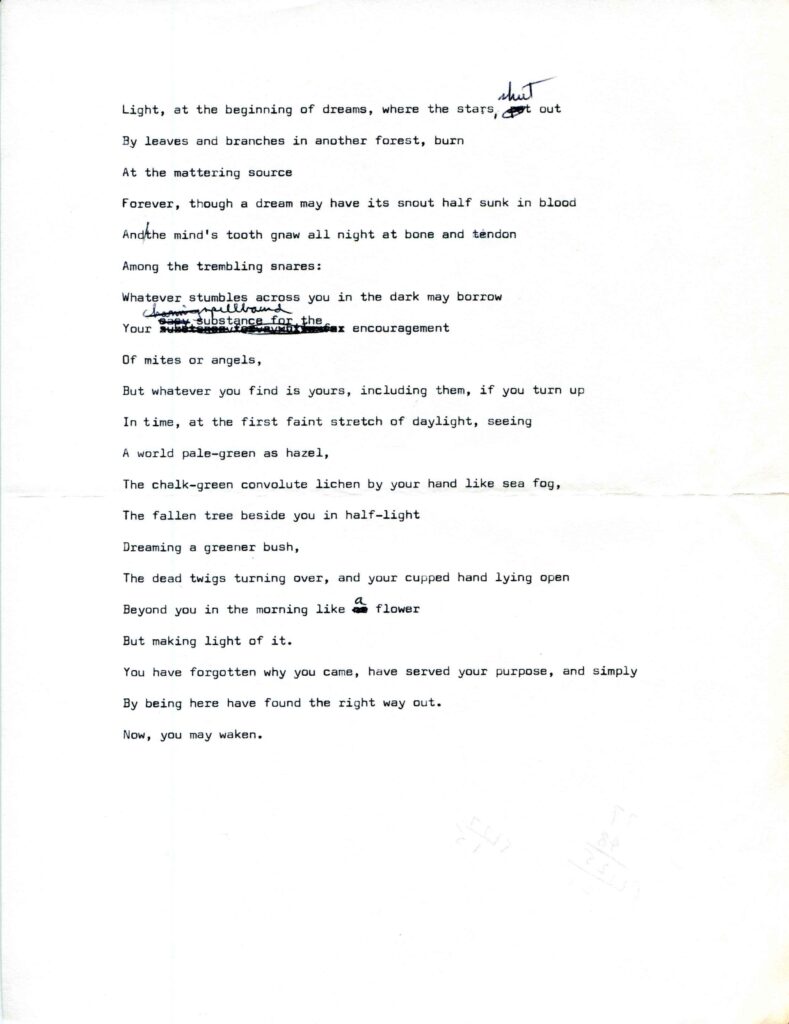

As mentioned, Wagoner’s poetry has long been associated with the Northwest, especially the wilderness and natural beauty of the region he called home—for example, see “Travelling Light,” “Lost,” “A Guide to Dungeness Spit,” “Staying Alive,” “A Pastoral Elegy for Pasture,” and “Sleeping in the Woods,” to name only a handful. In these and other poems, Wagoner explores the cathartic experiences of giving oneself over to nature.

In his monograph, The World of David Wagoner (University of Idaho Press 1997), Ron McFarland points to “Sleeping in the Woods” as being a remedy to his “unmediated pain and anger” over the destruction described in the poem “Elegy for a Forest Clear-cut by the Weyerhaeuser Company,” which immediately precedes it in the book, Sleeping in the Woods.

In the title poem, the speaker goes inward after being caught in the woods at night, communing with his animal nature as he drifts to sleep, and awakens in the morning with a simplified clarity that comes from being a part of his environment.

One could argue Wagoner’s most important but so-far overlooked poetic legacy is in bridging the back-to-nature idealism of pastoral poetry, that long predated him, with the ethical bent of eco-poetry that has been established by critics as a genre over the past twenty or thirty years. McFarland, in his article, “Can David Wagoner, Poet of Nature and the Environment, Qualify as Eco-poet?” (Rocky Mountain Review Fall 2017), presents Wagoner’s work as qualifying for inclusion alongside his well-known contemporaries W.S. Merwin, Mary Oliver, Wendell Berry, Gary Snyder, and others already associated with eco-poetics, aka postmodern pastoral poetry.

But as the New York Times obituary pointed out, Wagoner was adept at finding subtleties, insight, and awe in personal memories and everyday experiences as well, which his hundreds of published poems and corresponding folders of poetry drafts can certainly attest to. Wagoner was always alive to the little moments that might offer transcendence.

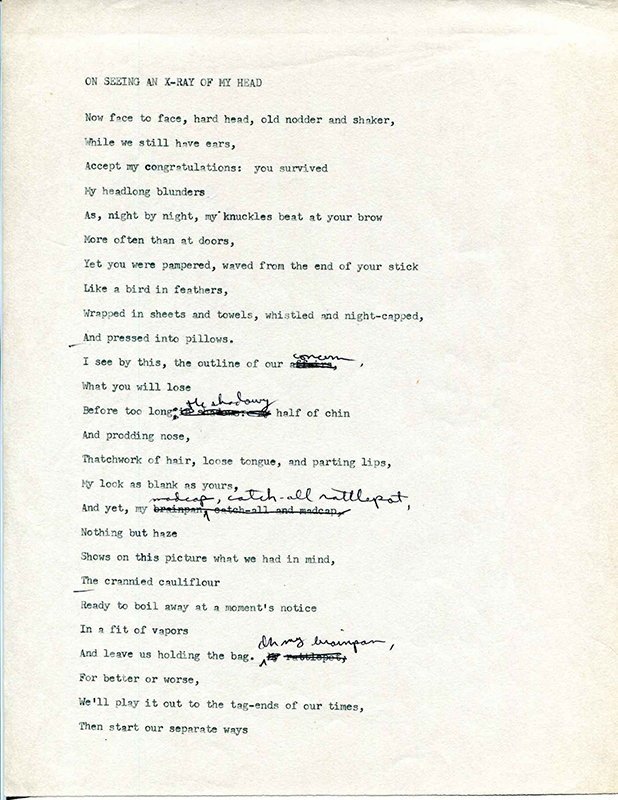

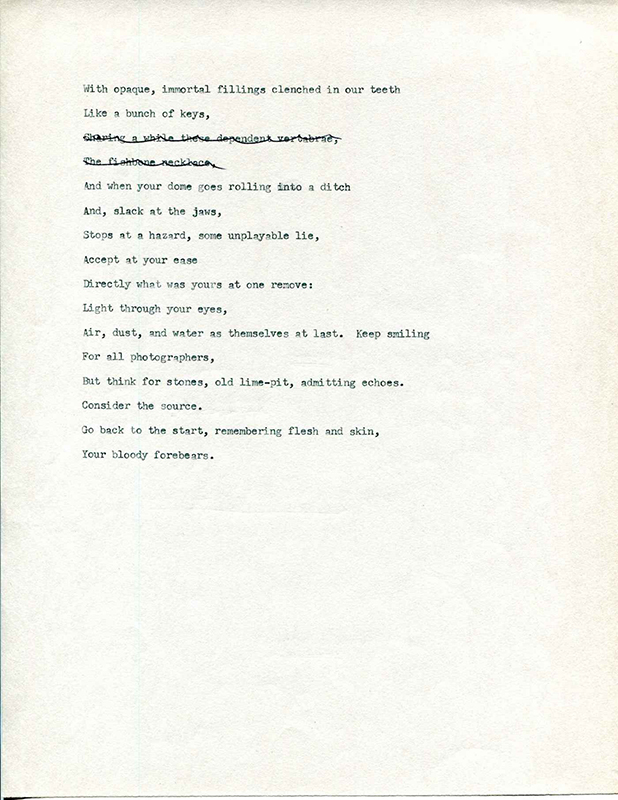

There is plenty of humor too. In his essay on Wagoner in Alone with America: Essays on the Art of Poetry in the United States Since 1950 (Atheneum 1980), Richard Howard (another esteemed poet who recently passed away) praises Wagoner’s “On Seeing an X-Ray of My Head” for its “witty relevance that is the consequence of a focused intelligence…to say so much about himself and about what he considers above himself…in a sense, it is the poet’s responsibility to speak above himself, beyond his means.”

Howard, writing in the mid-1970s, also calls it one of Wagoner’s “most ‘giving’ poems so far” and comments that “even the death that Wagoner had not dared consider as his own case becomes part of the converging energies of the poem. And humor—what Melanie Klein calls the effect of a benevolent super-ego—is the pervading companion of this quest for an existence beyond the self’s survival[.]”

You can read the final version of the poem from the Poetry Foundation, along with many others Wagoner published in Poetry over the years. I’d like to close this tribute with a transcription of the concluding poem of Sleeping in the Woods. In my opinion, this is a powerful example of poetry’s ability to connect death to birth, enabling us to better embrace life and the earth sustaining it.

Death Song

I touch the earth on all fours like a child,

And now my forehead touches the earth.

For the sake of my joys, Sleepmaker, let me in.

I have turned away from none of the six directions.

I have praised the rising and the dying wind,

Water falling or vanishing, even the end of grass.

I have welcomed the seasons equally

And been one with all weather from the wild to the silent.

The only blood left on my hands is my own: now my heart

Will be strict, admitting none, letting none go.

Close all my mouths. I will sleep inside of sleep,

Honoring the gift of darkness till it breaks.

I sing for a cold beginning.

From Traveling Light: Collected and New Poems. Copyright 1999 by David Wagoner. Used with permission of the University of Illinois Press.

All scans are from the David Wagoner Papers and you can find many more (along with more biographical information) in the Wagoner section of the MLC50 digital exhibit.