Celebrating Labor Day with the Sentner Papers

In celebration of Labor Day this Monday, we are highlighting the extensive and drama-filled collection of radical local labor organizer William Sentner, who fought hard to establish a livable wage in the midst of the Great Depression. Sentner, a St. Louis native, led District 8 of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers for over a decade, using community-based organizing strategies to raise the wages of even the most marginalized workers (like women of color) that other labor organizations had historically ignored.

The Life of William Sentner

Sentner was born in St. Louis in 1907 to Russian-Jewish immigrants who worked in the garment industry. His family was always short on money, but he was a bright student and was able to take advantage of a scholarship program that allowed him to attend Washington University. He studied architecture at the University until 1927 when his father died and he was forced to leave St. Louis to find work before completing his degree. He eventually ended up on the West Coast, where he encountered a radical seaman culture that was strong on militant organizing and exposed him to socialism, communism, and the writings of Carl Marx.

The Nut Strike and Community Organizing

Sentner eventually returned to St. Louis and became involved in the Unemployed Movement and the Trade Union Unity League, which existed to unite the employed with the numerous unemployed and create solidarity among the working class community. One of Sentner’s first major successes in the labor movement was with the nut-picker’s strike of 1933, in which black and white female workers united to strike against low wages and racialized pay scales. The strike, led by African American women from the Funston Nut Factory, effectively engaged other working-class community members, who brought feasts to the women on the picket lines to demonstrate that they were prepared for a long fight if necessary. The workers eventually received all of their demands, except for the recognition of their union. The community organizing techniques used in this strike laid the groundwork for future organization efforts. Rosemary Feurer, who draws on the Sentner archive in her book on District 8, writes, “The African American working class helped to develop a vision of unionism grounded in linking workplace and community struggle…the critical grounding that built a community-based social movement that later became associated with the CIO drive and defined radical unionism” (xviii).

Sentner’s Communist Politics

For the next fifteen years, Sentner engaged in many other organizing efforts, sometimes risking his own health and safety to fight for a living wage for others. After one strike with the Metal Workers Industrial Union, Sentner was thrown in jail and brutally beaten, after which he decided to officially become a card-carrying member of the communist party. Sentner was open about his communist affiliations, which many employers and anti-union politicians tried to use to discredit him, but most working and middle-class community members saw the fight for a living wage was a noble enough cause to allow them to overlook his radical politics, at least at first.

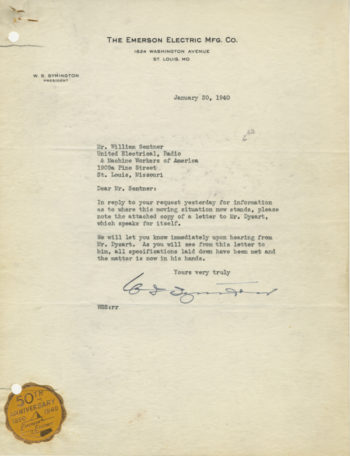

Workers were able to ignore Sentner’s politics because he employed a type of civic unionism that gave them much of the control over their own union. In supporting Sentner against accusations that he was part of a communist conspiracy, one worker writes, “Bill helped us build the kind of union completely controlled by the membership, which makes a joke of the talk of his ‘Communist domination’” (Friday, Charles T. “Record Here Explains Frame-Up In Sentner Trial, Says Friday” Evansville UE News, May 19, 1954).

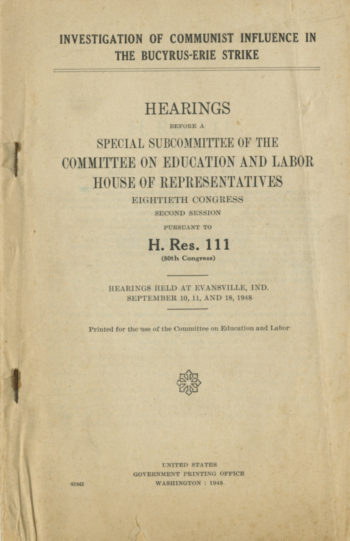

Eventually, however, red-baiting was successful in tearing apart District 8. After WWII, Sentner was accused of being a part of a communist conspiracy and fought a long battle against anti-communist sentiment before a loss of support forced him to forego seeking reelection to his position as head of the union at the end of 1948. Several other radical union leaders faced similar fates. In 1949, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) charged eleven unions with being “Communist dominated” and expelled them, setting up rival CIO unions in their place and diluting the unions’ strength.

Further Reading

The William Sentner Papers contains multiple boxes of material on District 8 and other unions Sentner was involved with, as well as material regarding his political activities and legal battles. The collection contains photographs, labor newsletters, collected news clippings about Sentner, legal and union documents, and Sentner’s personal correspondence.

For more information on Sentner and District 8, you can check out Rosemary Fuerer’s book Radical Unionism in the Midwest, 1900-1950, which draws on the Sentner archive. For more on the Funston Nut Strike, you might also see Myrna Fichtenbaum’s book, The Funston Nut Strike