Banned Books from our Special Collections

Banned Books Week is an annual awareness campaign promoted by the American Library Association (ALA) that celebrates the freedom to read. This year Banned Books Week runs from September 26-October 2, 2021. A number of books in our special collections have been banned or been the target of censorship campaigns over the years.

James Joyce’s Ulysses

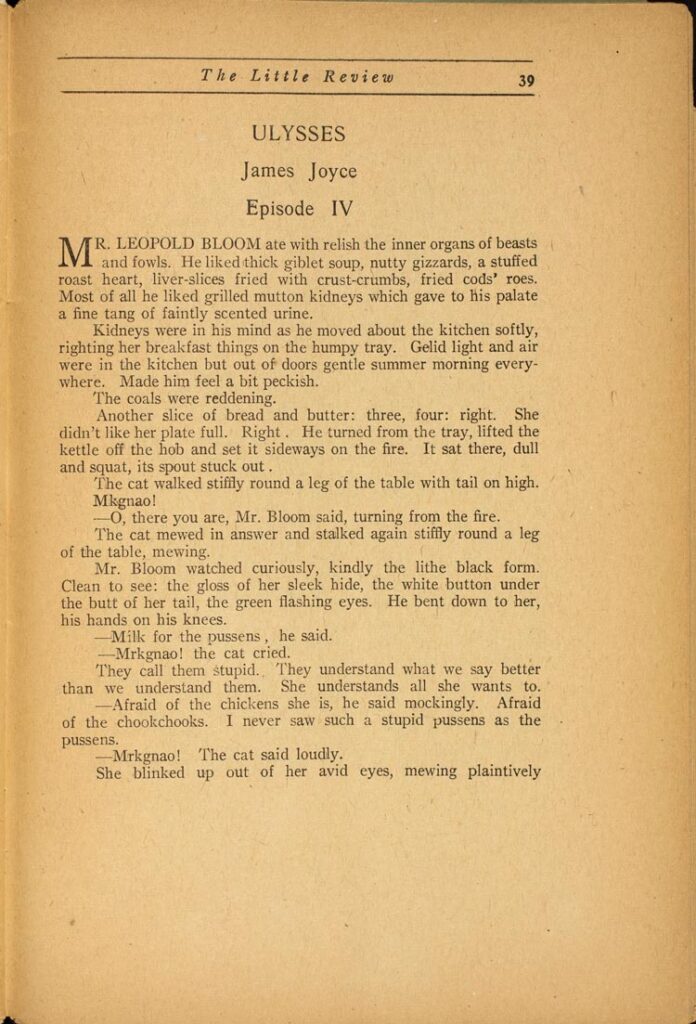

The publication of Ulysses by James Joyce spurred one of the first major literary censorship battles of the 20th century. Ulysses shocked readers both with the frank content about sexuality and with Joyce’s attitude towards the Catholic Church. With its highly experimental form, eschewing traditional punctuation and structure, this modernist classic evoked strong feelings from both general readers and critics alike.

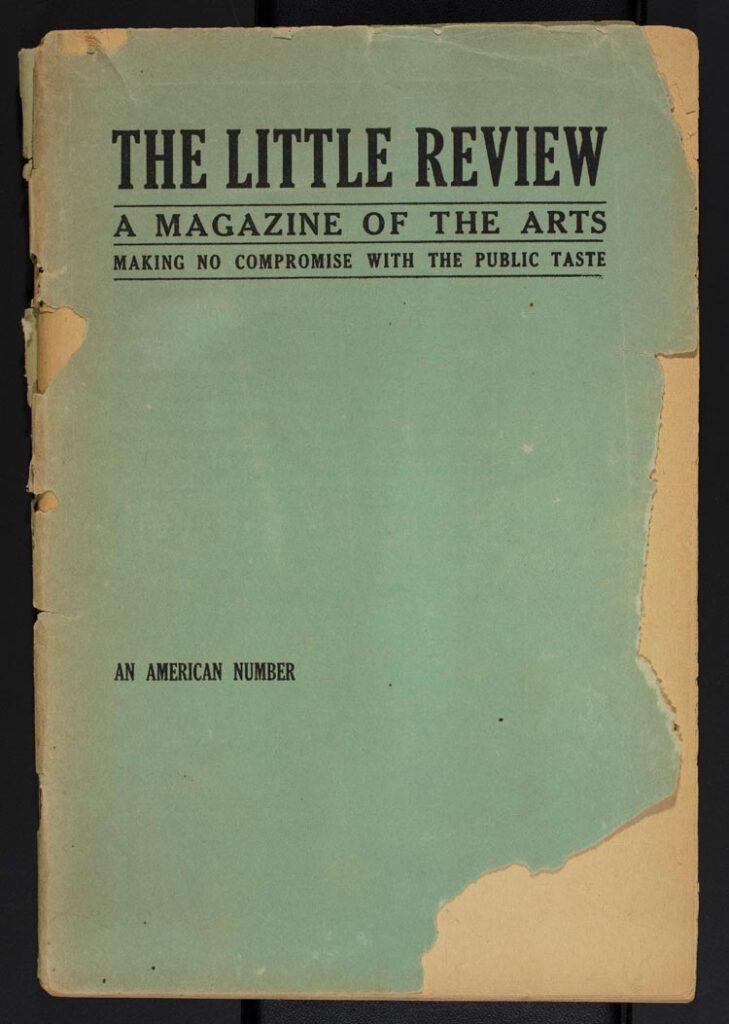

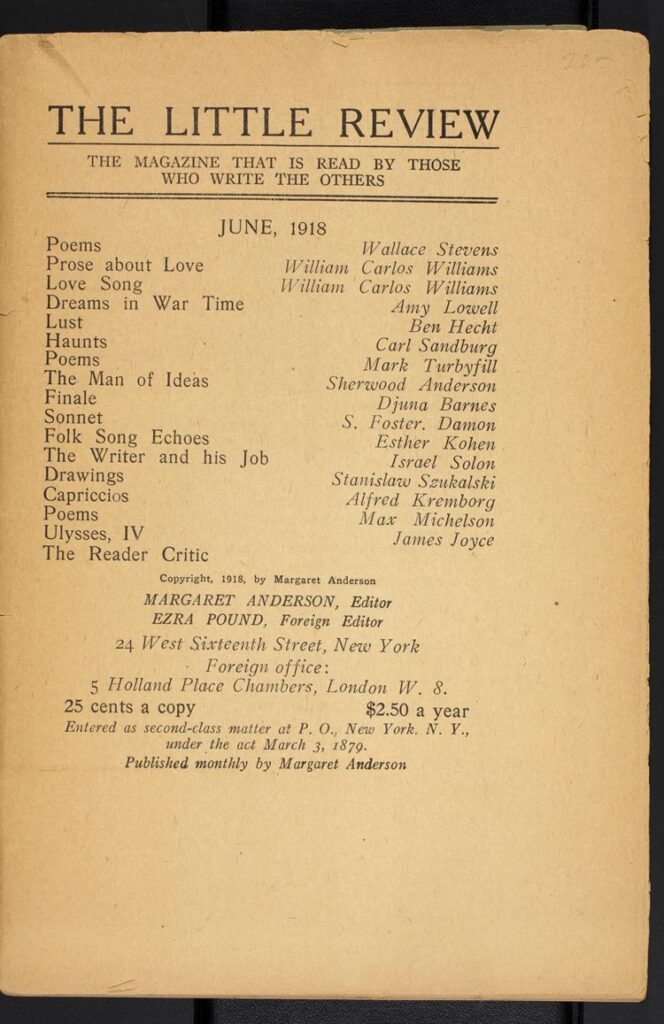

In the late 19th and early part of the 20th century, printed material that was deemed obscene was seized under a set of legislation known as the Comstock Laws, named after its main proponent, Anthony Comstock. Ulysses was originally published in a serialized and edited form in The Little Review, a literary journal founded by Margaret Anderson, from 1918-1920. One of the editors, the writer Ezra Pound, made changes to the text to make it less likely to be censored. Despite Pound’s edits, the text garnered the attention of a New York lawyer who was shocked when his daughter received a copy of the magazine. The resulting court case banned Ulysses in America, and the publishers Jane Heap and Margaret Anderson were charged with obscenity.

Special Collections holds some of these volumes, both the serialized Little Review issues and several copies of different complete editions of Ulysses.

Above: Cover, title page, and page featuring a section of Ulysess. The Little Review, v.6:no.2, May 1918

Another tactic that publishers used to skirt the censors was to publish controversial English-language books in foreign countries. Sylvia Beach, a supporter of Joyce who owned a bookstore and press in France called Shakespeare and Company, took on the publication of Ulysses in 1922. She sent the book to subscribers of Shakespeare and Company in England, America, and other countries, although it was often intercepted and confiscated or incinerated.

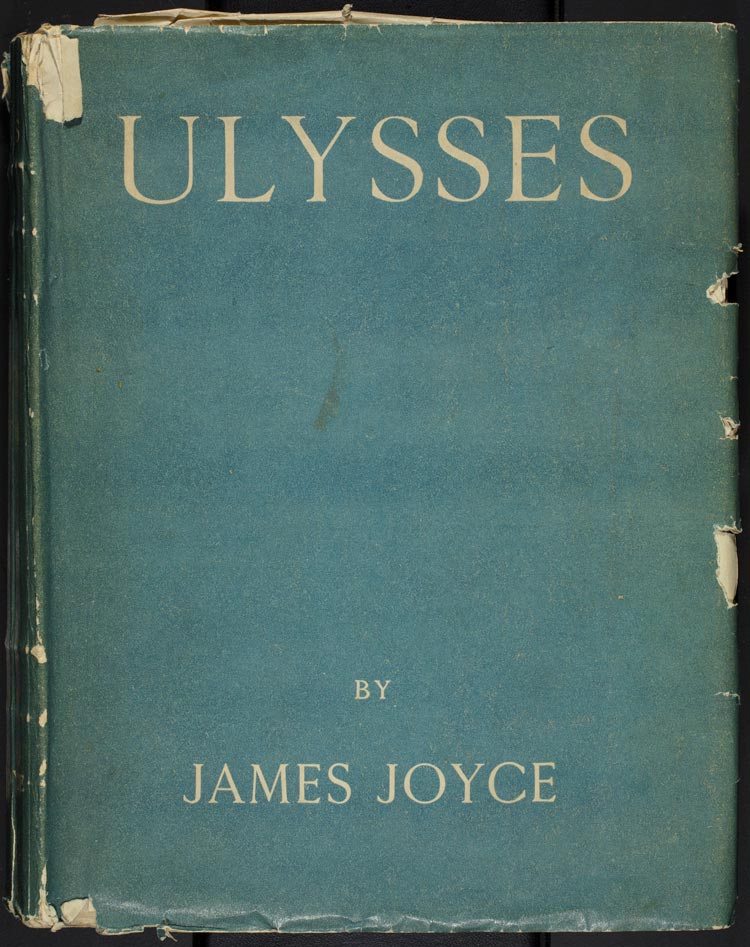

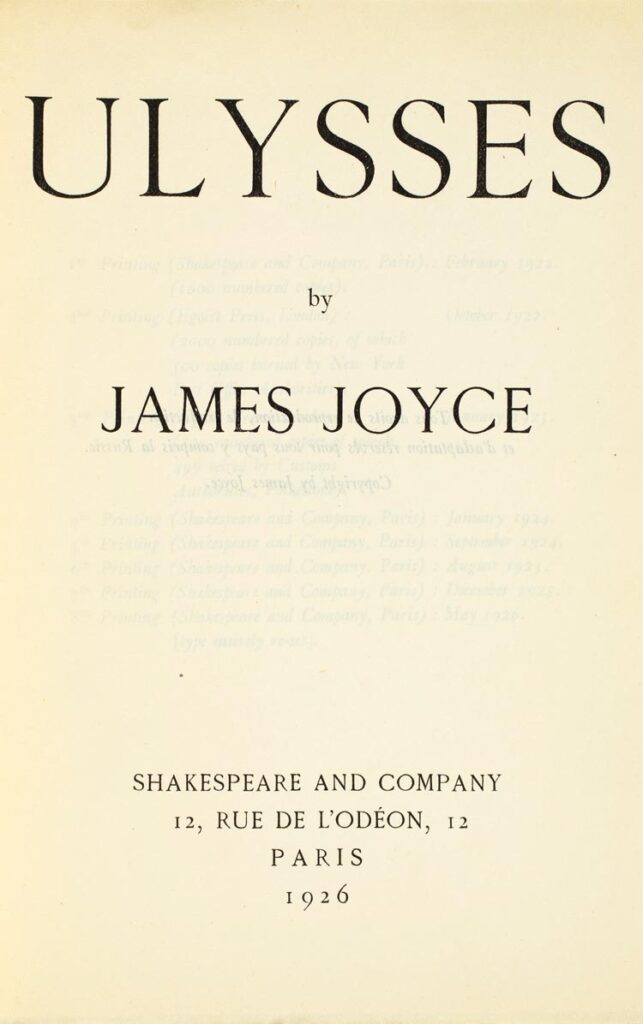

Above: Cover and title page of Ulysses by James Joyce. Paris: Shakespeare and company, 1926.

Ulysses was eventually published legally in the United States after a 1933 court case, United States v. One Book Entitled Ulysses, reached the Supreme Court. Spurred on by the publisher Random House who wanted to dispute the obscenity charge in court, the court ruled that Ulysses “is not obscene and therefore entitled to enter the United States.” Judge John M. Woolsey said that “Whilst in many places the effect of Ulysses on the reader undoubtedly is somewhat emetic, nowhere does it tend to be an aphrodisiac.”

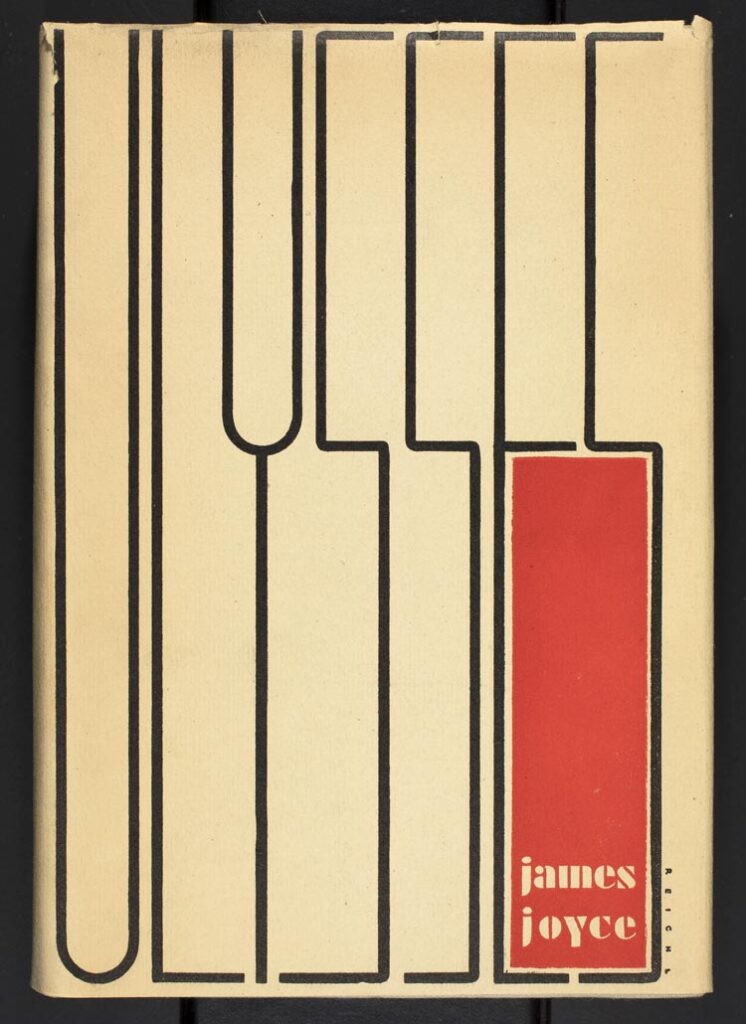

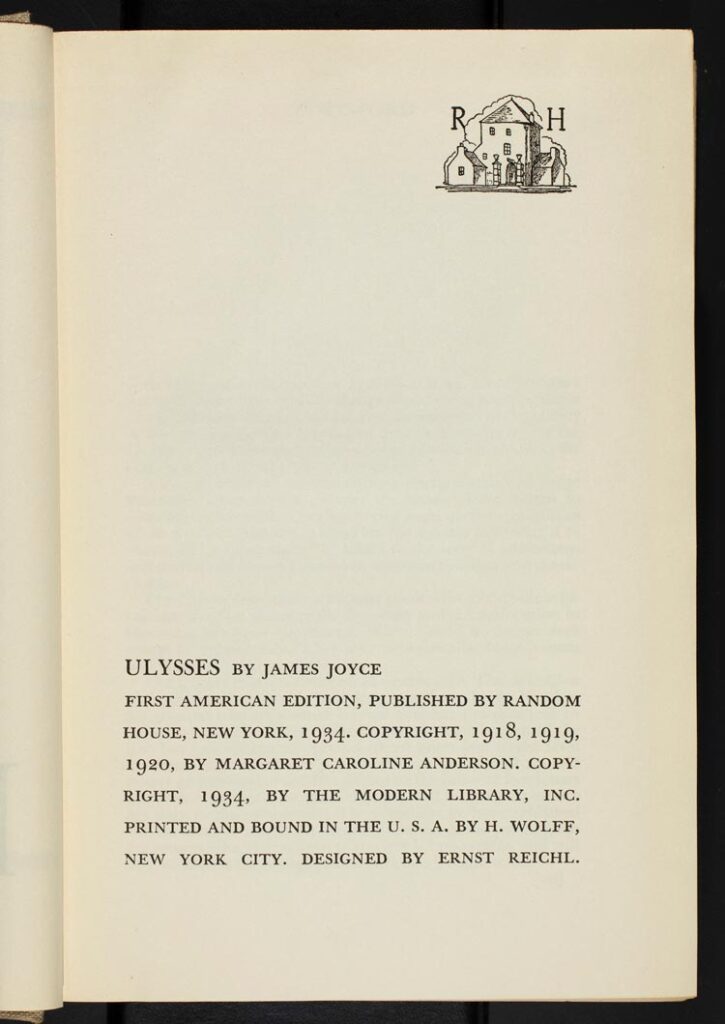

Above: Cover and publisher’s note from the first authorized American edition of Ulysses (New York: Random House, 1934)

William Burroughs’s The Naked Lunch

Another book whose publication resulted in a landmark obscenity trial was The Naked Lunch by William S. Burroughs.

Surprisingly, Burroughs first book, Junkie, an autobiographical novel about his drug addiction, escaped the censors’ scrutiny. Possibly because it was published by Ace Books, a company that specialized in pulp and exploitation fiction, thereby not attracting the notice of libraries or literary critics.

That changed with The Naked Lunch, a structurally innovative novel that came under scrutiny for its subject matter of drug use and sexual content. Publisher, Olympia Press, based in France used the earlier tactic of publishing an English-language book in France and then exporting it to English-speaking countries.

Above: Cover and title page of The Naked Lunch by William Burroughs. Paris: Olympia Press, [1959]

The case involving The Naked Lunch (Attorney General vs. A Book Named “Naked Lunch”) took place in Massachusetts in 1965-66. Witnesses in defense of the book included established writers such as Allen Ginsberg, Norman Mailer, John Ciardi, and others. Mailer said, “Reading it through this last time, I had the feeling that the work presents a kind of complexity which I will not compare to James Joyce’s Ulysses, I’d say it is not without comparison… I found it considerably less shocking as I read it this time… There is a kind of speech that is referred to as gutter talk that often has a very fine, incisive, dramatic line to it; and Burroughs captures that speech like no American writer I know.”

Despite this testimony by Mailer and others in defense of the book, it was judged obscene. However, in 1966, during an appeal, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of the defense and that the book did not violate obscenity statutes as it had some social value.

Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings

In the past 50 years, censorship and book suppression comes less from legal rulings and more from localized, focused efforts including conservative organizations, school boards, and parent groups. Often times a book will come to the attention of a parent or group by being on the reading curriculum, and they then launch a campaign to have the book banned or removed from a school’s reading list.

Maya Angelou’s 1969 autobiographical novel I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings drew from her early years and described the sexual abuse, rape, and racism she endured as a child and the aftermath. The book’s unflinching frankness and descriptive power won it many favorable reviews and it was a best-seller, but it also made it a target of censorship as some parents called for the book to be removed from curriculums.

Starting in 1983, the book faced a series of challenges from various groups and organizations including the Alabama State Textbook Committee, parents whose children attended schools in Washington, California, Texas, Georgia, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, to name just a few. Complaints ranged from objections to the sexual content to claims of the book being “anti-white.”

The American Library Association (ALA) lists the book on the list of the 100 Most Frequently Challenged Books of 1990–2000. Despite these challenges, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings continues to be taught and read in schools across the country and has never been out of print.

In 2017, Angelou told the Orange County Register “I’m always sorry that people ban my books. Many times I’ve been called the most banned. And many times my books are banned by people who never read two sentences. I feel sorry for the young person who never gets to read.”

Sources:

Bradshaw, David. “Ulysses and Obscenity.” The British Library. The British Library, May 25, 2016. www.bl.uk/20th-century-literature/articles/ulysses-and-obscenity#authorBlock1. Accessed 21 Sept. 2021.

Chamberlain, Katherine. “Spotlight on Censorship: I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. Intellectual Freedom Blog, September 26, 2010. https://www.oif.ala.org/spotlight-on-censorship-i-know-why-the-caged-bird-sings/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2021.

Doyle, Robert P. “66. Angelou, Maya. I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” Banned Books: Challenging Our Freedom to Read. American Library Association, 2014. pg 98-99

United States Circuit Court of Appeals… United States of America, libellant-appellant, against one book entitled Ulysses by James Joyce. Random House, Inc., claimant-appellee. Brief for claimant-appellee. New York, United States Circuit Court of Appeals, 1934. www.bl.uk/collection-items/legal-notes-prepared-for-united-states-v-one-book-entitled-ulysses-1934. Accessed 21 Sept. 2021.

“The Boston Trial of Naked Lunch.” Reality Studio. realitystudio.org/texts/naked-lunch/trial/. Accessed 21 Sept. 2021.

“100 most frequently challenged books: 1990-1999.” American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. Banned and Challenged Books. www.ala.org/advocacy/bbooks/frequentlychallengedbooks/decade1999. Accessed 21 Sept. 2021.