Animal Tales in the Henrietta Hochschild Collection

From mischievous bunnies to fearsome wolves, animal characters grace the pages of the majority of picture books beloved by young children such as those found in the Henrietta Hochschild Collection of Children’s Books in the Washington University Libraries.

Using animals to impart lessons, like language or natural history, was a common practice for children’s authors throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, and by the 20th century, commonly referred to as the “golden age of children’s literature,” illustrated animal tales were staples of childhood (The British Library, 2015). The role that animals play in these whimsical narratives—whether wild or anthropomorphized—varies greatly, depending on shifting beliefs about childhood and the personal goals of the authors and illustrators.

Several excellent examples of the various types of animal tales from the Hochschild Collection are discussed below. Housed within the Rare Books Special Collections, this remarkable collection of children’s books—most of which are not available in the circulating library stacks— offers students and researchers the opportunity to study these important visual and historical artifacts.

Animals as Human Representatives

In many animal tales, the main characters serve not as representations of the animal kingdom but function as furry representations of human beings. In these stories, animals adopt unnatural roles for wild beasts—they wear clothing, demonstrate complex thought processes, and even speak—resulting in dressed-up versions of human characters. Fables are a classic example of this type of tale, in which authors communicate human lessons of virtue and morality using animals, whose endearing fur and whiskers were thought to make didactic and moralistic content more palatable for children.

Modern trends in child development have questioned whether children require such direct moral lessons (Heneghan, 2018). As a result, recent examples of the animal-as-human tale tend to focus on friendship or self-acceptance as opposed to behavioral lessons. Regardless of the time period or subject matter, examples abound in picture books of animals living life as humans.

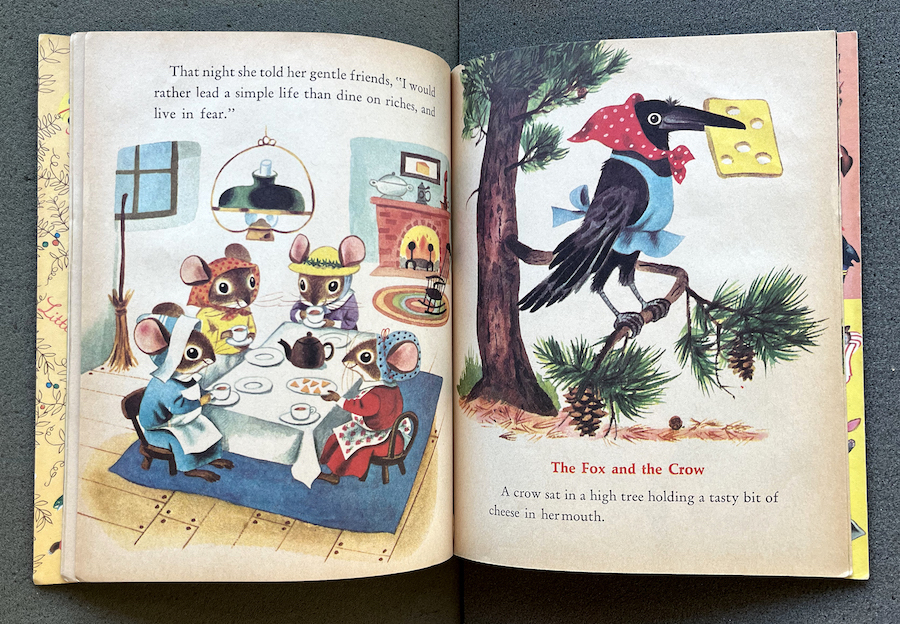

The 1961 book The Country Mouse and the City Mouse by Patricia Scarry is a classic example of the anthropomorphized animal. In this trio of fables, animals play the role of foolish humans learning lessons the hard way. A country mouse discovers that big city luxuries are not all that they seem, a crow learns to be wary of sweet-talking strangers, and a dog finds that greed will leave him empty-handed. While the characters retain some aspects of their animal nature, they mostly masquerade as humans, donning fancy hats and taking tea by the fire.

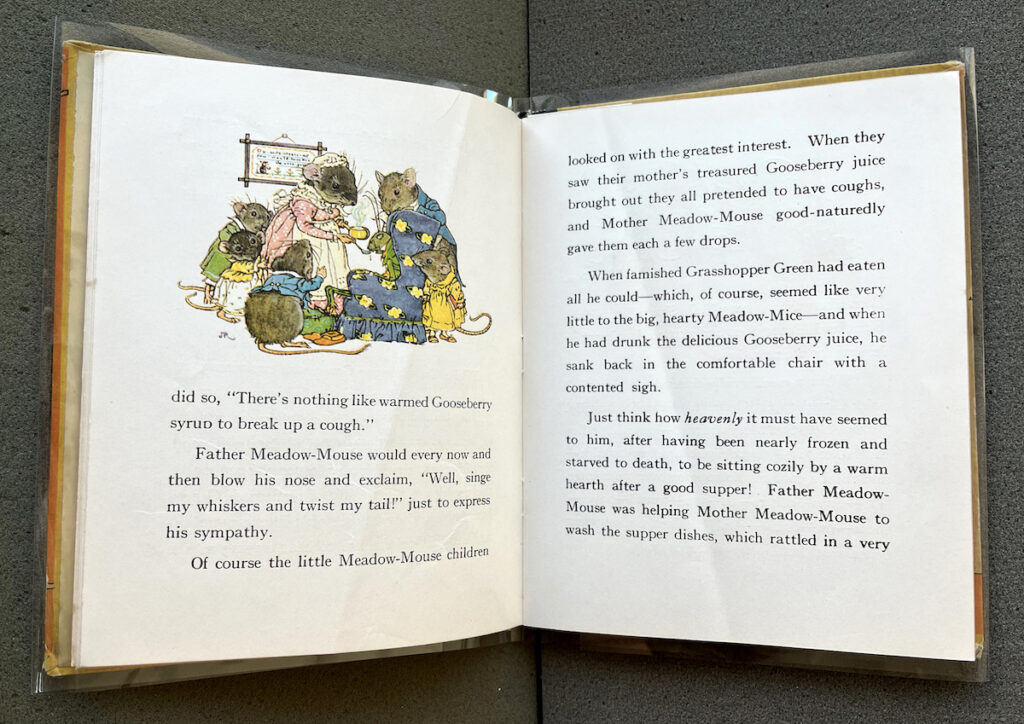

Another fable-centric example of the animal-as-human tale is the 1922 book Grasshopper Green and the Meadow Mice by John Rae. In this picture book, a grasshopper who finds himself unprepared for the brutal winter is taken in by a kind family of field mice. The grasshopper marvels at the family’s fine, very human-like furnishings, including tablecloths, curtains, and a framed motto above the fireplace reading “do unto others as you would have them do unto you”—the explicit moral of this tale.

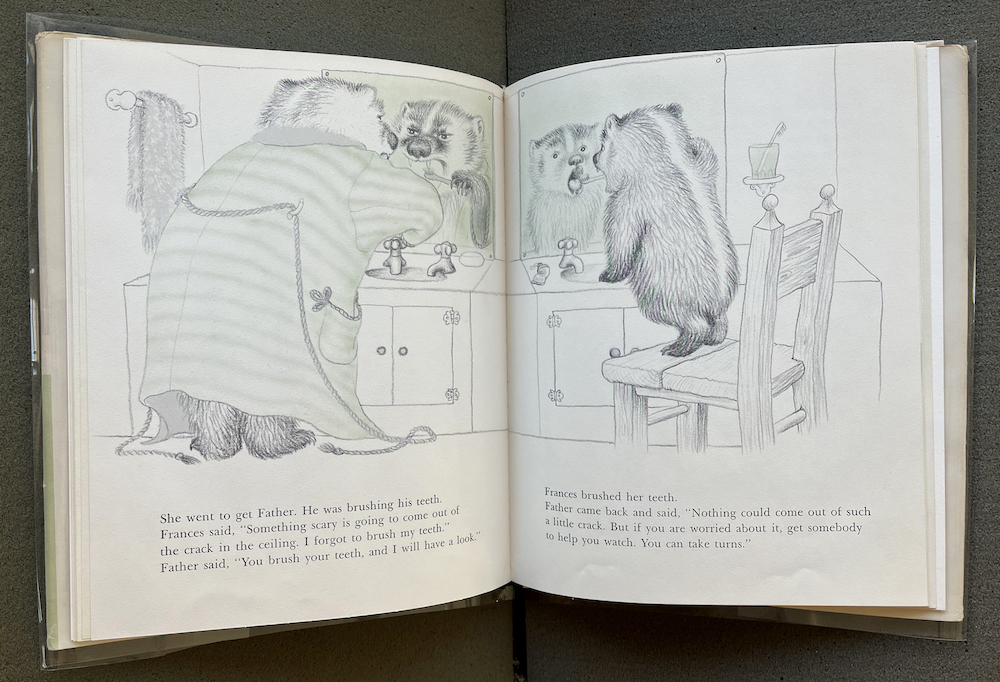

Finally, in a tale that any human parent will immediately relate to, the 1960 book Bedtime for Frances by Russell Hoban grants a family of badgers an almost fully human existence. In a tenacious attempt to avoid sleep, Frances repeatedly gets out of bed citing concerns about dark shadows and strange noises as her parents listen with dubious amusement. Other than their physical appearance, these badgers fully inhabit human life, brushing their teeth in bathrobes and dreading their early morning school and work routines.

Animals as Wild

In contrast to the animal-as-human tale, many picture books for children allow animals to remain wild, woodland creatures that exist adjacent to but distinctly separate from the sphere of human life. They retain animal-like qualities typically appearing unclothed and in their natural habitats. While some books grant wild animals complex thought, these creatures tend not to speak, their motivations and behaviors disclosed by an all-knowing narrator. Humans in these stories, when they are present at all, emerge either as companions or quiet observers.

Tales of wild animals serve many purposes for children in picture books. Early examples of wild animal tales taught children empathy for animals and encouraged their humane treatment, particularly during periods when humans relied more directly on animals for transportation and labor (Ratelle, 2015). Wild animal tales also provide opportunities for informational lessons that foster environmental ethics and a sense of curiosity about nature (Heneghan, 2018).

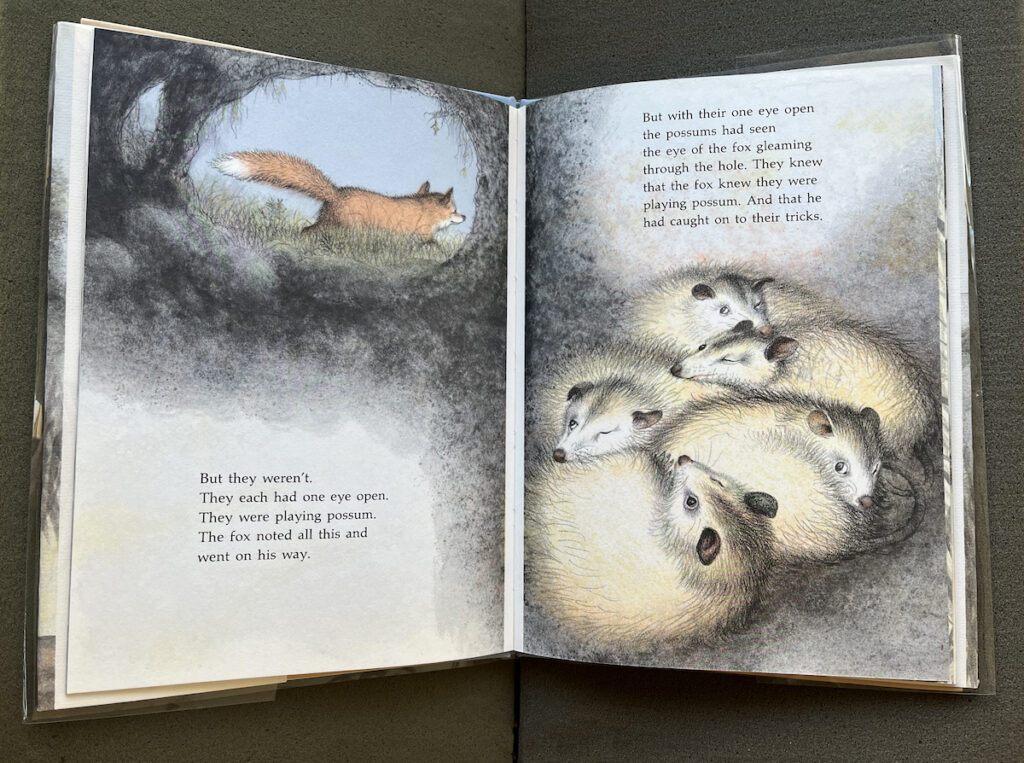

Fox Eyes by Margaret Wise Brown, published in 1951, is a classic example of the wild animal tale. A sly fox slinks around the forest spying on the other creatures and learning their much-guarded secrets. The presence of humans in the book reinforces their separation from the animal world. With no morals or lessons, this picture book provides a playful glimpse at the unique characteristics of each animal.

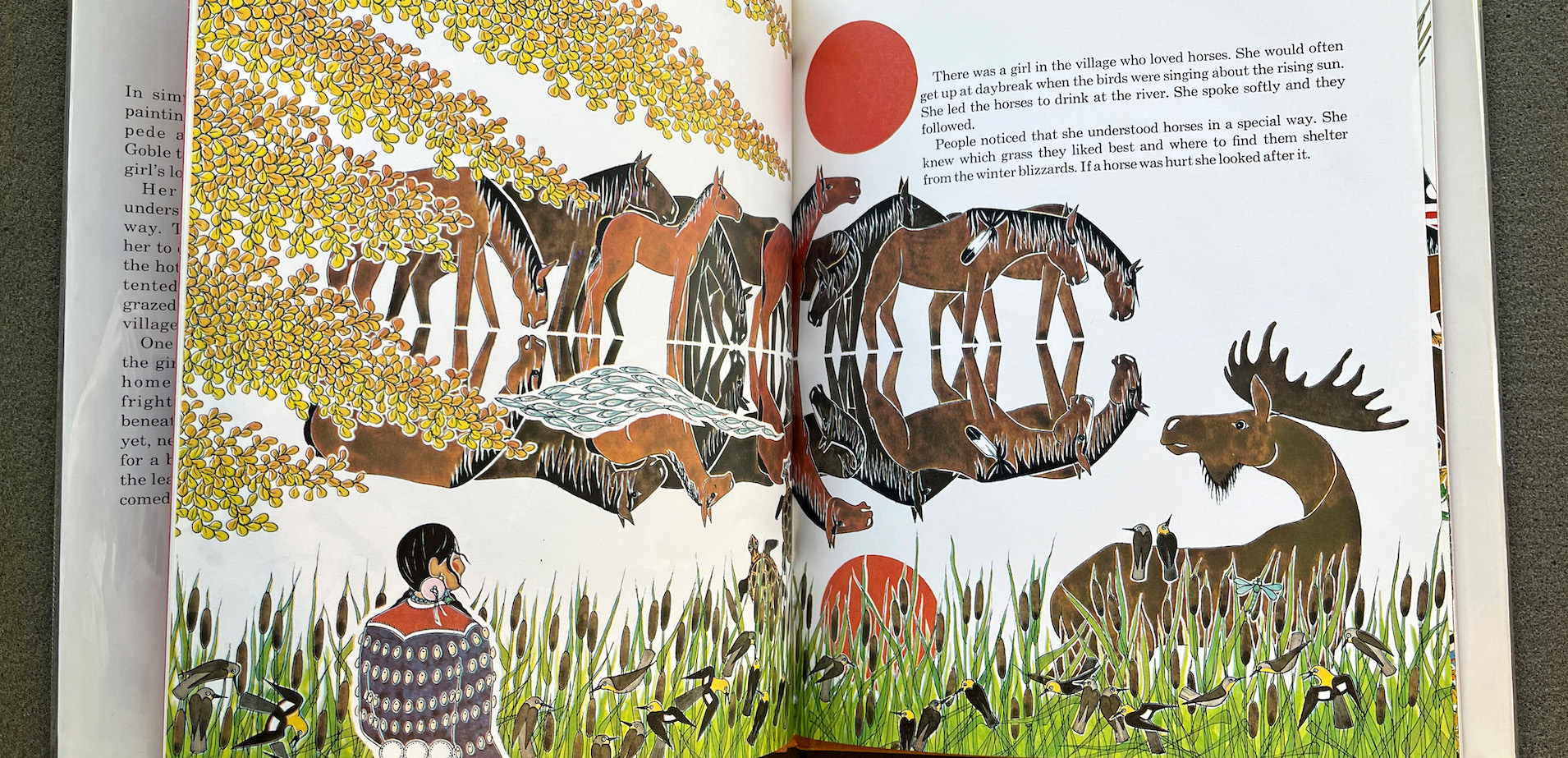

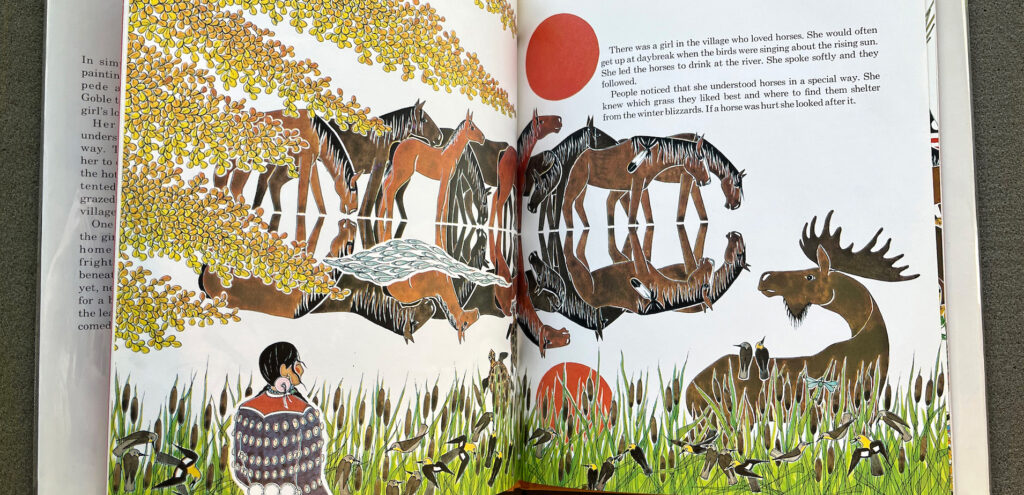

Another beautiful example of a wild animal tale is the 1978 Caldecott-winning picture book The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses by Paul Goble. When a young Native American girl gets caught in a violent storm, wild horses carry her to safety and welcome her into their family. The relationship between the young protagonist and her beloved horses mimics the close bond many children feel towards animals and highlights themes of interspecies harmony and companionship.

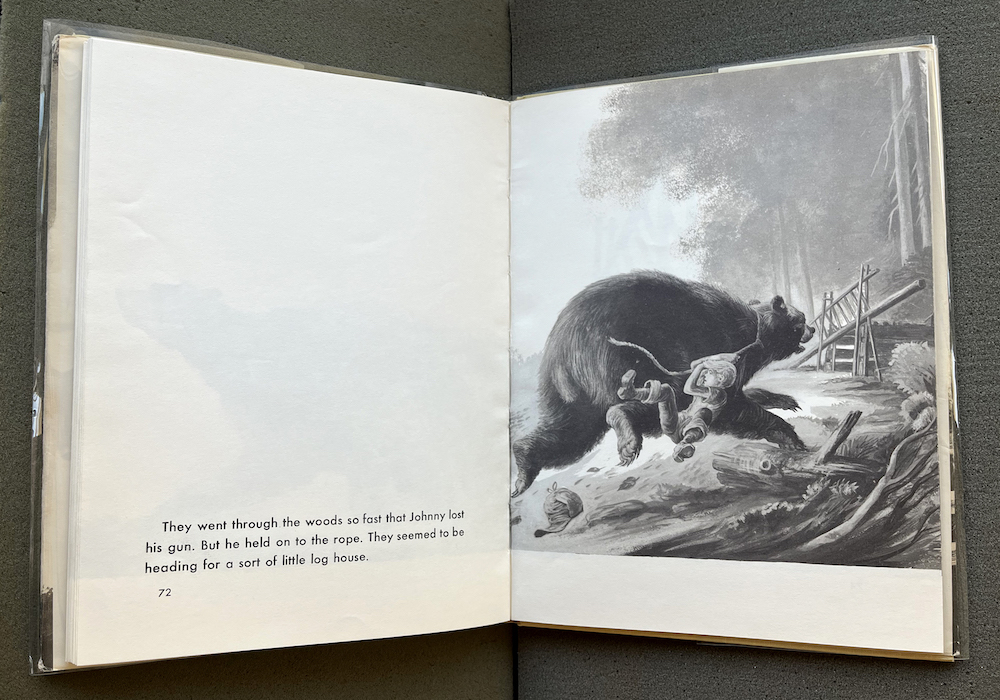

The 1952 Caldecott-winning book The Biggest Bear by Lynd Ward also features a story of love and companionship between a wild animal and a human. When a young boy goes bear hunting in keeping with family tradition, he instead befriends and adopts a bear cub whose presence as a farm pet causes countless problems for both. Far from inhabiting human traits, the bear’s wildness is highlighted by his clashes with the human world and his resistance to domestication.

Many children possess an innate kinship with animals that is celebrated and enhanced through picture books. The ubiquity of animals in children’s literature often leads to readers taking their presence for granted, but delving more deeply into their symbolism and narrative roles provides unique perspectives into changing viewpoints about childhood and the animal kingdom.

For more information about picture books in the Henrietta Hochschild Collection of Children’s Books, please contact the Curator of the Rare Book Collections Cassie Brand.

Sources Cited

- “Children’s Animal Tales.” The British Library, November 10, 2015.

- Heneghan, Liam. Beasts at Bedtime: Revealing the Environmental Wisdom in Children’s Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018.

- Ratelle, Amy. Animality in Children’s Literature and Film. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Danielle Ridolfi is a master’s student in the Illustration and Visual Culture Program at Washington University.