Interview with Poet and Washington University Faculty Member Mary Jo Bang

When Washington University Libraries’ Modern Literature Collection was initially created in 1964, all but two of the forty-six writers in the original collection were still living. Today, the collection has grown to more than 175 authors, presses, and journals, with much of the archive still being purchased or received as donations from living authors. We interviewed one of these authors, Washington University’s own Professor Mary Jo Bang, about her decision to sell her manuscripts to Washington University and some of the interesting elements of her collection.

Save the Date

On November 30th, the Julian Edison Department of Special Collections will be hosting an event to celebrate Mary Jo Bang’s collection of manuscripts in the Washington University Modern Literature Collection. You can find more information and RSVP here.

About Mary Jo Bang

Mary Jo Bang is an American poet and a professor in the Washington University English Department. She is the author of eight books of poetry, the most recent of which is A Doll for Throwing (Graywolf Press, 2017). She has won numerous awards and fellowships, including a Hodder Fellowship from Princeton University, a grant from the Guggenheim Foundation, and a Berlin Prize fellowship at the American Academy in Berlin.

The Mary Jo Bang Papers in Washington University Libraries’ Modern Literature Collection consists largely of her own manuscript materials, including drafts of individual poems, book reviews, essays, introductions and translations, as well as editorial material toward her published and unpublished books. Also included are personal journals, college work, artwork, printed materials, ephemera, teaching and conference materials, personal and business correspondence, and material relating Bang’s editorial work for the Boston Review.

Interview with Mary Jo Bang

Rose Miyatsu: In the past, libraries generally acquired an author’s manuscripts and correspondence after she died, usually without her explicit consent. Now it is relatively common for authors to sell their materials to Special Collections while they are still alive and publishing. What made you decide to sell your materials to a library in general, and Washington University specifically?

Mary Jo Bang: I believe it was in the late 60’s when I read in a biography of Anais Nin that she had tried to sell her papers to a library. That was the first I was aware that libraries collected writers’ papers. I seem to recall that she was in need of money. Ever-practical, I must have filed that away in my mind, because years later, when I began to write, I kept my manuscript drafts, thinking it was unlikely that a library would ever value my papers enough to acquire them but also knowing that the future was unknown. It was never front and center in my mind, only a half-thought at the back. Over time, I wrote a number of books, co-edited Boston Review magazine for ten years, became a professor at Washington University, translated Dante’s Inferno, and participated in the larger world of poetry by judging prizes and supporting the work of other poets. When the library asked to acquire my drafts, notebooks, and correspondence, I was happy I’d kept the papers, even though early in my career it had seemed rather silly. I’m deeply touched that there are those who feel there might be people who will have an interest in these things after the fact of my existence.

RM: Did you have any hesitations about selling your materials to a library, particularly when it comes to things like personal correspondence? How do you negotiate privacy as a writer?

MJB: I don’t have hesitations because I have an agreement with the library that any personal materials—journals, correspondence, etcetera—won’t be available except through special permission until after my death. I received that idea from the Emily Hale papers at Firestone Library at Princeton. The 1,131 letters from T.S. Eliot to Emily Hale, were donated by Hale in 1956 under the stipulation that they remain—

“completely closed to all readers until the lapse of fifty years after the death of Mr. Eliot or myself, whichever shall occur later. At that time the files may be made available for study by properly qualified scholars in accordance with the regulations of the Library for the use of manuscript materials. To carry out this intention the Library is to keep the collection in sealed containers in its manuscript vaults.”

In the case of Emily Hale’s letters, the sealing is not just figurative, the letters are literally bound by steel bands attached to a wooden base and kept in a vault. My letters are not strapped down, I’m not such a literalist, but they will only be available after my ashes have joined any others in the blue beyond. Incidentally, the Eliot/Hale letters will be available beginning January of 2020.

RM: Why do you think it is important for libraries to collect authors’ materials? What do you think (or hope) people can gain from looking at your archive?

MJB: Ephemera oddly conjures the sense of the hand that created or touched whatever we are now holding in our hands, here in the present. Stein doesn’t come back to life, a scientific impossibility, but for a brief moment her presence is sensed when we hold a copy of the original 1914 Tender Buttons, with it’s ivory-colored card-stock cover where her given name, G E R T R U D E S T E I N, stands above the larger type-point book title, T E N D E R B U T T O N S, and below it is the secondary title Objects ∴ Food ∴ Rooms, each of those three words separated by what is called in logic a ‘therefore sign’—if this, therefore that. At the bottom on the book, there’s the name of the publisher, date, and place of publication: CLAIRE MARIE ∴ 1914 ∴ NEW YORK.

Each of those elements and the overall appearance ‘read’ as that date, that place, that person, that press, and that literary moment. In Stein’s case, it’s a landmark moment both because it was her first publication and because what she published was highly innovative for its time and it continues to influence poets writing a hundred years later. When that book is now held in the hand, it conveys a certain weight that reading about the work, or seeing a photocopy of the work, doesn’t convey. The hand has nerve endings that communicate with the brain; together they insist on the material reality of what is in the hand. In that way, we experience something of the previous time. It feels like this means it felt just like this. It’s similar to the experience of hearing a voice on tape of someone who once lived but is no longer alive, the vibrations in the air, held as evidence of that utterance, now hit our ear and reproduce the sound. She sounds like this translates into that IS her.

If Stein’s work has meaning to us, its force is increased when we hold a piece of it in our hands. Perhaps the key is that archives concretize the fact that humans are linked over time. The objects chart the course of literary history and allow future beings to connect with previous beings. This is the tragedy when there is a large-scale destruction of objects created by previous generations. We become estranged from the idea that we are part of a lineage, part of a long train of women and men who drew on cave walls, built edifices, and made marks on paper. Awareness of our shared humanity might be necessary to undermine a natural human arrogance that argues that our moment (whenever that moment is) has nothing to do with the past. That we are more evolved, better positioned, and more-or-less invincible.

The narrative of my becoming a poet is a long digressive one. To have all the ephemera that represents those efforts in one place creates a story about how one, or at least how this one (me, I), became a poet. And because it took such a very long time, I wouldn’t mind if seeing what I created might give another person encouragement that if one persists, sometimes it is possible to realize one’s ambition to become a writer—an ambition that, if strong enough, becomes over time an obsession or compulsion.

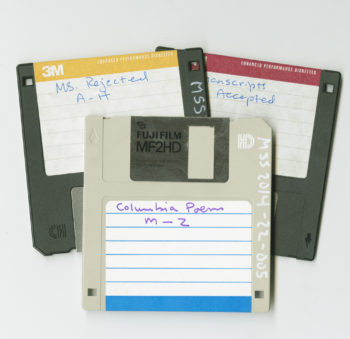

RM: You are one of the first artists in the Modern Literature Collection to include digital materials in your manuscript archives. How have computers altered your writing process?

MJB: Before computers, I composed by hand, often in notebooks. I then typed a draft on a typewriter. I made revisions by hand on that typed draft, and then typed a new draft, and on and on. I also kept journals by hand, writing in notebooks or sometimes on sheets of loose paper. I wrote and received letters written by hand, an activity that now seems almost precious and may in time come to seem as quaint as Victorian scrapbooks.

In terms of the poems, I think the computer invites revision, perhaps because it’s so relatively easy compared to retyping an entire poem. The poem goes on feeling unfinished for longer. Even after months, I may go back to a poem on the computer that I had once considered finished and begin making changes. It’s as if the poem is still in process because it can still be in process. One can easily erase and replace a word or move lines around or retitle the poem. The ease invites you to rethink what you want to say. And of course you’re a different person now, if only by a few days or weeks or months. And so the new ‘you’ thinks differently and writes with new knowledge.

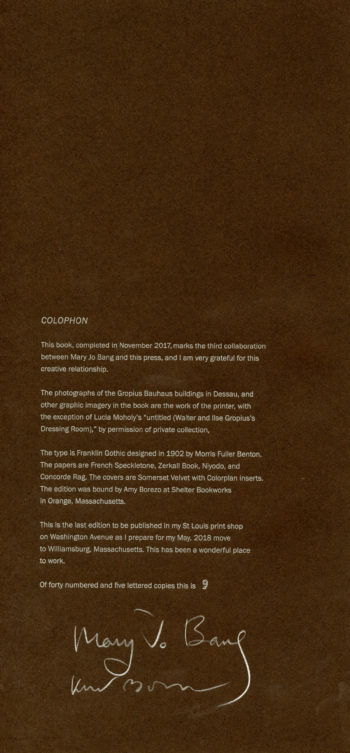

RM: Washington University Libraries own three beautiful artist books of your poetry created by Ken Botnick. Could you say something about what it was like to work with Botnick? How much did you contribute to the designs of “B is for Becket” and “The Circus Performer”? How do you think the form of the book transforms the reading experience of your poem?

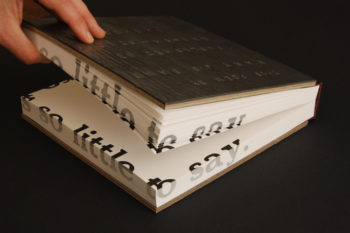

MJB: I didn’t contribute to the design of Ken Botnick’s artist books. I only contributed a poem that was based on what he told me he had in mind. With “B is for Becket,” he asked if I knew of any one-line poems or perhaps had written one myself. And in fact, I had. And that particular poem—“ ‘B is for Becket’: There is so little to say ”—was an excellent match for the brevity and concision of the book he wanted to create, where the single line wraps around the three-sided page edge of the book.

With “The Circus Watcher,” Ken asked for a poem of fewer than a certain number of lines, where each separate line of the poem would be printed on the front of a closed book. He then intended to stack the books/poem-lines so that the poem would read vertically. Because “The Circus Watcher” measures out its meaning in bite-size pieces, I thought it might be a good fit, and in the event, Ken thought so too. He had a clear Plexiglas case made to hold the stack of books and the black edges of the individual book covers create the sense of lined paper.

I think Ken is an amazing book artist because he works three-dimensionally. Even when dealing with what is on the page, he has in mind the actual space the book will occupy. The result is that the reader appreciates the book as text and as object.

There’s an architectural quality to that way of thinking and it’s exciting for a reader to take in a text that insists that it also has a place in the three-dimensional world. The place Ken creates reveals his wit and intelligence and there’s tremendous pleasure in that. A double pleasure, as it were, the pleasure of the text and the surprise and interest in how the text will now occupy a space that seems perfectly designed for it, because the space so imaginatively echoes the words on the page.