ACLU-MO History Spotlight: Reforms to End Police Violence

Once again, as I write about the ACLU of Missouri’s history of trying to stop police violence, I do so as I listen to news stories of protesters met with tear gas and rubber bullets. As updates scroll by on my newsfeed about a black man, already in handcuffs, murdered by a while police officer. And I am reminded that while these events of 2020 are horrific, they were equally horrific in 1946, and 1967, and in all the other years past. These events are heartbreaking and difficult to face, but only with the light of awareness can we have any hope for the future.

Reforms to End Police Violence

Since the earliest years of the organization, the ACLU of Missouri (then known as the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee) has “maintained a persistent interest in the encroachment upon the right and liberties of citizens by illegal and improper police practices.”

Much of this work involved investigating after police violence occurred and pressing for the courts to hold police accountable, especially for attacks on African Americans. The 1946 shooting death of William Howard, an African-American Army veteran, is just one example of this effort.

Awareness of the problem grew over the decades, and by the 1960s half of the Committee’s work was focused on issues of police misconduct and violence. Monthly minutes from 1965 described this work as: “the ever-present problem of police brutality…”

While investigation into specific cases continued in the 1960s (then and now), the ACLU of Missouri began to examine the systems (or lack of systems) that allowed police violence to occur. What protected officers from facing any consequences for excessive use of violence? How could policies and procedures change to ensure equal justice? Some of these efforts are outlined below.

Reform Efforts

1960s

1962: Volunteers Eugene Buder and Benjamin Rush form an ad hoc committee aimed at meeting with representatives of police departments and police boards to discuss areas of concern.

1965: St. Louis volunteers send a systematic analysis of firearm usage the St. Louis Board of Police Commissioners, noting areas of particular concern:

- police shooting at moving cars

- shots fired by officer for petty crimes

- lack of complaint procedures

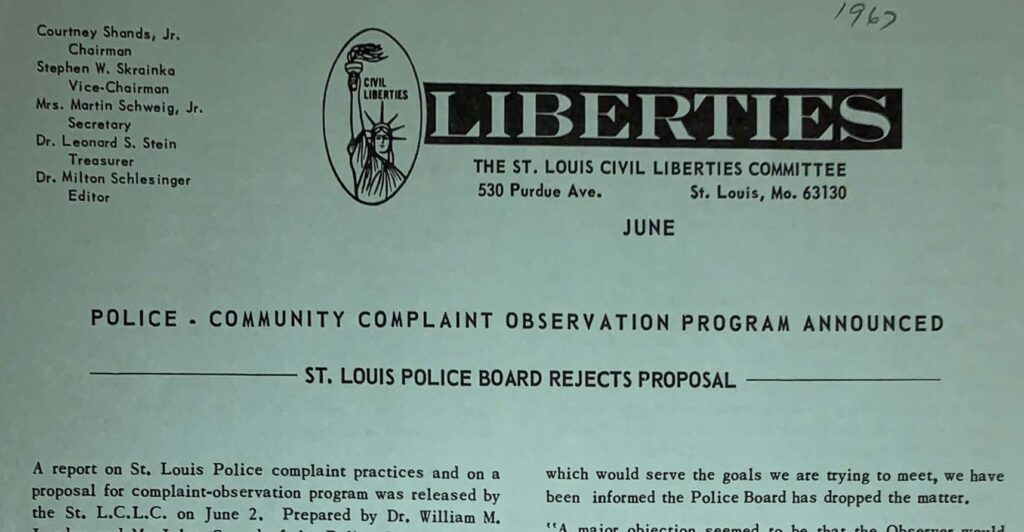

1967: The “Community Complaint Procedures Program” is presented to St. Louis Mayor Cervantes and the Police Board in April. It is rejected in June 1967 without further discussion.

From ACLU-MO Records wua00355, series 1, subseries 1, box 4, SLCLC Publications, 1961-67

An editorial by St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee noted,

“…During our last year police complaint activities brought to our attention have proved more improper and inadequate than we had supposed. … We have heard no citizen complaints this year which have led to the conclusion that the officer was reprimanded or disciplined for wrongdoing. We find such a batting average difficult to believe for any organization of fallible human beings.”

St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 8, 1968

A revised “Police Complaint Procedures” is presented to both St. Louis city and county police in 1971. Some provisions were enacted by the police, but only informally.

1970s and 1980s

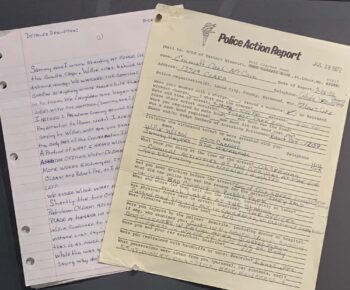

A “Police Action” form is created in 1970 to track the increasing number of civilian complaints reported to the ACLU of Eastern Missouri.

An early example is Emmet Carl McCain, an African-American student at Forest Park Community College, who reported his arrest for “bad conduct in a park,” while visiting the zoo. Multiple witnesses heard police swearing and hitting McCain.

1977: The ACLU of Eastern Missouri begins lobbying for “decertification” laws to prevent neighboring police forces from rehiring abusive officers.

This policy shift was spurred by the 1977 death of Thomas E. Brown (a mentally disabled man shot while handcuffed at the Maplewood police station). ACLU board president Roger Goldman realized that although the officer “was fired by Maplewood, he was subsequently hired by Bridgeton Terrace, where he fatally shot a suspect.” Decertification became law in Missouri in 1988.

1990s and 2000s

1992: St. Louis police representatives reach out to community groups after the police beating of Rodney King in California. Together with the NAACP and ACT-UP, the ACLU of Eastern Missouri creates a “Community Bridges Report” recommending:

- police diversity training

- increase in minority-officer recruitment

- transparent complaint procedures

While endorsed by Board of Governors for Law Enforcement in 1994, implementation is voluntary by St. Louis’ 60+ police forces.

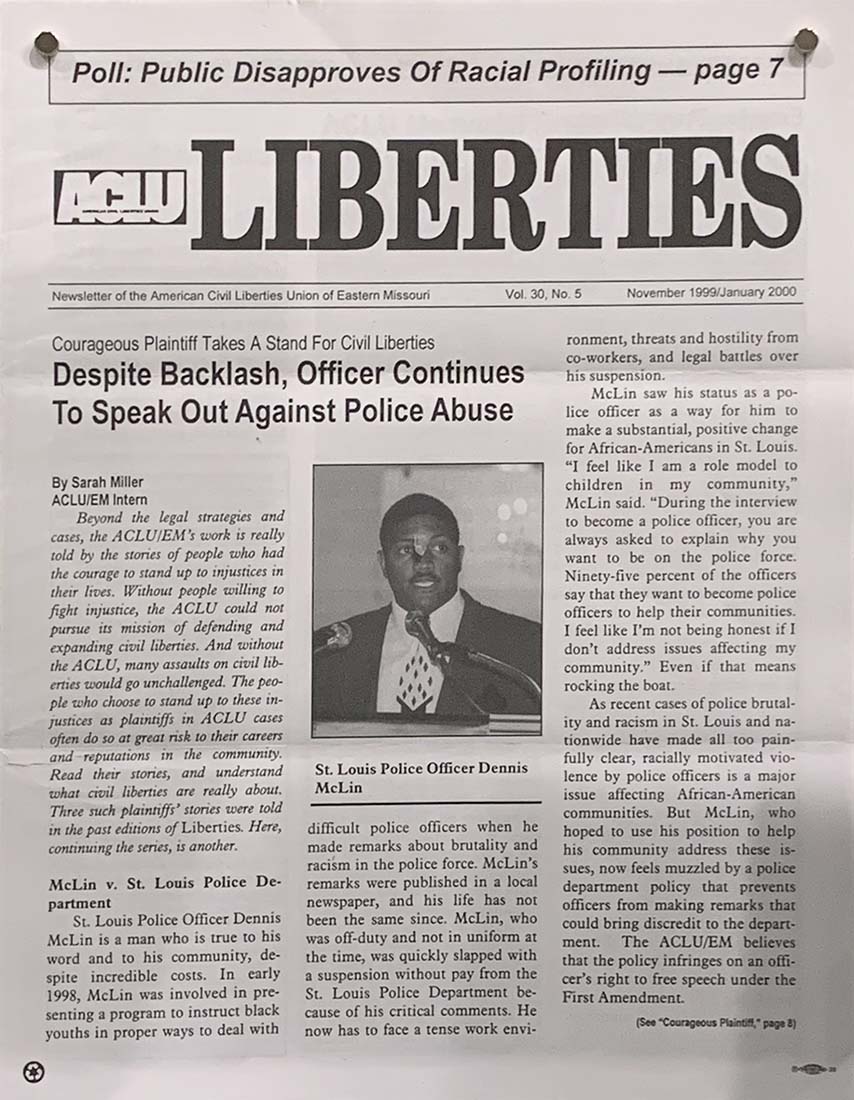

1998: Officer Dennis McLin, an African American, remarked to a youth group that “abuse and racism are rampant in the police force.” Despite being off-duty and out of uniform, McLin is suspended without pay by the city of St. Louis.

The ACLU of Eastern Missouri appealed his case, McLin v. St. Louis Police, to the 8th District Court, but it was denied in 2001.

Contemporary Work

Various methods and actions were tried to marginal degrees of success starting in the 1960s. The victories have been slim since then, but the ACLU of Missouri continues to work for systematic change. In 2014, in the aftermath of the fatal shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson. In 2017, following violence against people demonstrating after the acquittal of Jason Stockley.

And, it seems, this work must continue in the 21st century.

More

ACLU-MO @ 100

This post is part of a series in recognition of the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri’s centennial year (1920-2020). Read more stories at: ACLU-MO @100 in Our News

If you have a question about this post or other topics related to St. Louis history, I can be reached at mrectenwald@wustl.edu or on Twitter: @mrectenwald.