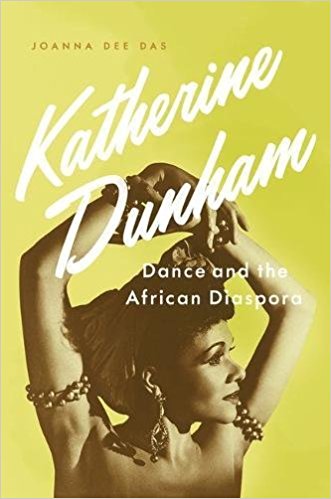

In ‘Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora,’ Das Explores the Life of a Legendary Performer

Joanna Dee Das is an assistant professor of dance in WU’s performing arts department. In her new book, Katherine Dunham: Dance and the African Diaspora (Oxford University Press), she explores the life and work of Katherine Dunham (1909-2006), the pioneering dancer, choreographer, teacher, writer, and activist, who used dance in the struggle for racial justice.

A native of Glen Ellyn, Illinois, Dunham was interested in dance and performance from an early age. She studied anthropology at the University of Chicago and in 1935 traveled to the Caribbean to conduct ethnographic research, with a focus on dance traditions—a trip that influenced her work as a performer. Dunham founded a groundbreaking black dance troupe, which toured for nearly three decades, beginning in the 1930s. She also established a number of schools, including the Performing Arts Training Center in East St. Louis.

Das has lectured widely on Dunham’s contributions as a dancer and an activist. We recently caught up with her for a q-and-a.

You write that Dunham brought “dance into the conversation about how to build a sustainable cultural foundation for political activism.” For Dunham, how did dance function in the context of political activism? Dunham came of age during the New Negro Movement, in which her peers were advocating for the use of poetry, literature, music, and theater to push for racial equality. She was determined to bring dance into that matrix. She took a fusion approach to her choreography, bringing together her training in ballet and Euro-American modern dance with movements and aesthetic approaches she had learned in the Caribbean. This choreographic mode accomplished two goals: one, it demonstrated that black dancers could perform in the genres deemed “high art,” and two, that black cultural practices had a place in that high art realm.

Dunham’s choreography was not just about convincing white America that African Americans were equal; it was also about demonstrating to black America the cultural richness and connectivity of the African diaspora. Her dance productions featured between 15 and 20 short dances set in places throughout the African diaspora, with her choreographic aesthetic as a thread that linked the dances together. Coupled with her husband John Pratt’s sets and costumes, the shows enveloped audiences in a worldview that placed black culture at the center. Her shows helped African Americans see themselves not as an oppressed minority, but rather as part of a global majority.

What do you consider Dunham’s most important legacy? Dunham has many legacies, and which one is most important depends on the current moment. If you asked me this question ten years ago, I would say that it was her dance technique, which greatly influenced the development of modern and jazz dance.

Now I think it is her artistic activism, and in particular, her internationalism. We are in a political moment that threatens to divide us—by race, by nationality, by ethnic identity—and Dunham was firmly committed to finding the connections among people and building community that respected, even celebrated, people’s differences even as they came together. I can think of no better model than Dunham for how one should navigate the world today.

You studied Dunham technique and are now a certified instructor of that technique. Can you describe it? Dunham technique, as she liked to say, is a “way of life.” Physically, the technique combines aspects of ballet, modern dance, and Afro-Caribbean movement. It is highly structured, meaning that it is about having clear lines of the body, precise rhythms, and specificity with your movement in space.

At the same time, the technique is also a life philosophy, as it is all about intercultural communication, bringing together things that seem different to create coherence. Many of us today feel that we live our lives pulled in many different directions. Dunham Technique helps you become more holistic.

How widespread is that technique today? Is it flourishing or in danger of becoming extinct? At the moment, it is neither flourishing nor in danger of becoming extinct. Instead, it is slowly but steadily growing, especially in cities such as Detroit, Dallas, San Francisco, and right here in St. Louis. At Washington University, both I and MFA candidate Heather Himes are certified to teach Dunham Technique, and we are excited for students to experience it.

If Dunham were alive today, what words of advice do you think she would have for young dancers/artists and activists? Don’t give up hope. Keep dreaming of a better world and put that vision into your artistic practice to share with others. The political situation may seem bleak now, but it was just as bleak for Dunham during her lifetime, with lynching, Jim Crow, Cold War repression, FBI suppression of Black Power, etc. Yet she never gave up hope, never gave up creating the world she wished to see in her dance performances, in her schools, in how she lived her life.

Do you think dance can play a role in the current era to inspire social change? Yes! Dance artists can embody visions of a better world. They can remind us of our past and current problems, so that we remain aware of the challenges we face, but they can also guide us on the path forward. Artists make the seemingly impossible possible.