Nineteenth and Early Twentieth-Century Illustrated German Periodicals

Though historical periodicals are increasingly available in digitized form, accessing the print original can allow us to better imagine their original readers. Often shared in the family home or perused in a café, German-language periodicals provided German readers with information, entertainment, and inspiration. Readers could see images of distant wonders before Google Image searches, play games, enjoy divertissements before Candy Crush and Wordle, and learn from in-depth reports on new technological innovations before YouTube videos and Netflix documentaries.

After the 1848 revolutions in Germany, some modest liberal reforms were introduced including an easing of the strict press censorship. Along with an advancement in infrastructure and technology that allowed for the increased development of mass printing, as well as a significant increase in literacy, this set the stage for an explosion of illustrated periodicals.

Both our special collections and general stacks contain bound volumes of mass-printed periodicals from Germany, and these are a few of the highlights.

Family Magazines and a New German Identity

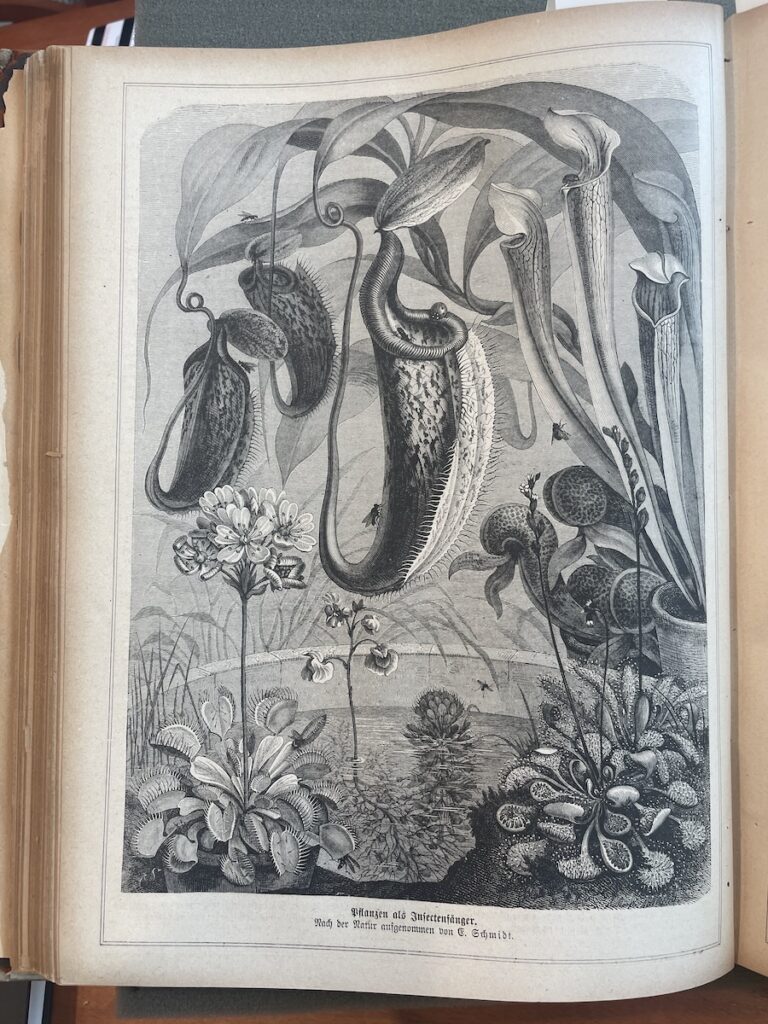

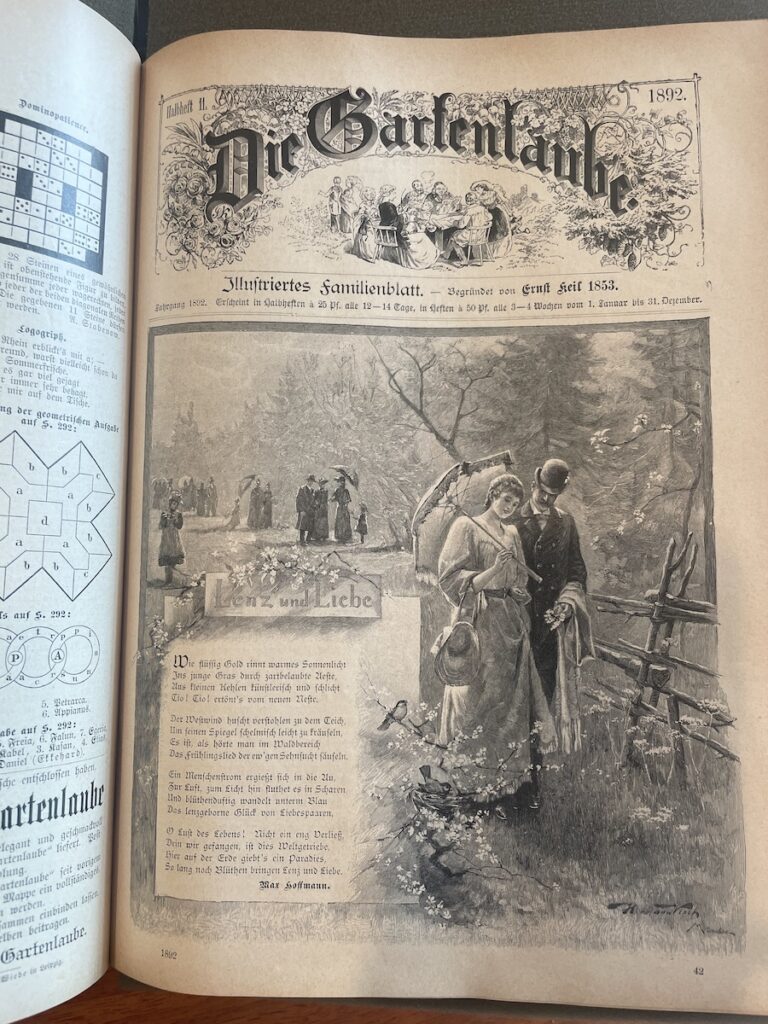

Die Gartenlaube was founded in 1853 by Ernst Keil. The weekly publication aimed to be of interest to middle-class German-speaking families across many varied regional identities that make up modern Germany. Die Gartenlaube provided accessible accounts of technological advances, illustrated historical narratives, and serialized fiction.

Though Die Gartenlaube did not take explicit partisan political stands, Keil was committed to the liberal ideal of a unified Germany, and of his magazine being a vehicle to educate the German-speaking populace. The library’s holdings contain most issues printed from 1866 to 1892, a time when the Gartenlaube was at the height of its popularity, and tracks the shift from a burgeoning German identity to unification in 1871, to the more imperial ambitions of the German empire under Kaiser Wilhelm II later in the century. The issues have also been digitized by other libraries and are available in Hathitrust.

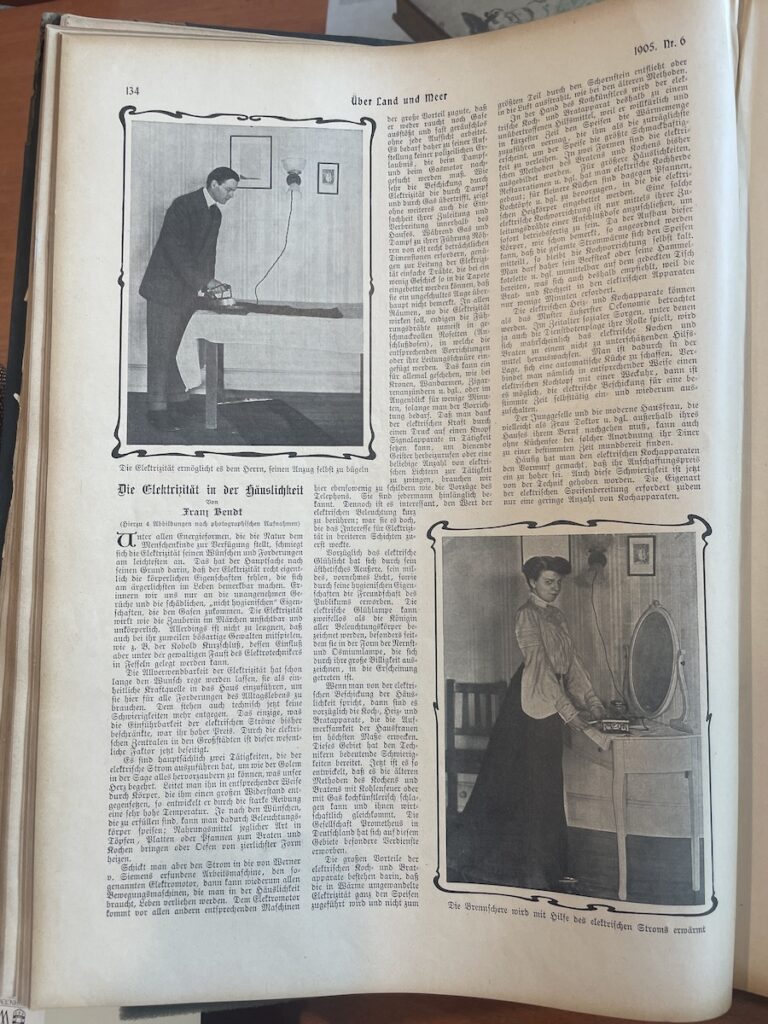

German Empire and Colonialism

The German empire and its foray into colonialism that began in 1884 is on more explicit display in Über Land und Meer, a larger and more glossy illustrated periodical. Like Gartenlaube it kept Germans abreast of the latest technological innovations and provided a window into the world, though with a more sharply colonialist viewpoint. WashU Libraries have select volumes spanning 1905 to 1911, a period of increased militarism leading up to World War I. Digitized copies can be accessed in HathiTrust.

Style and Trend Setters in the Modern Nation

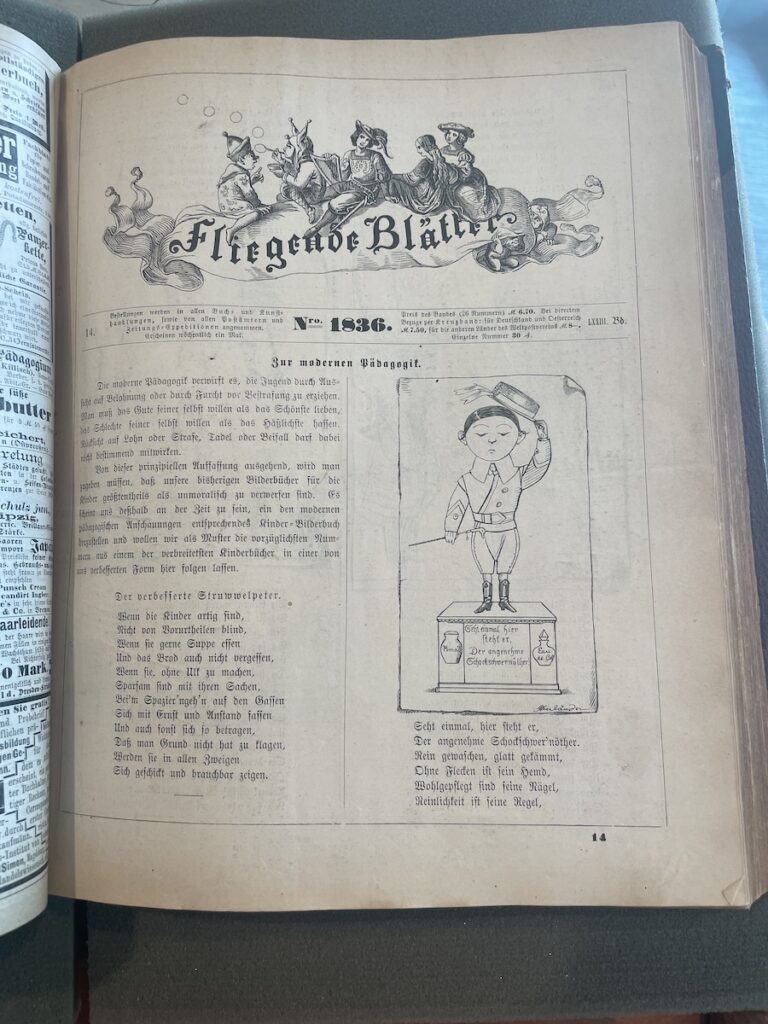

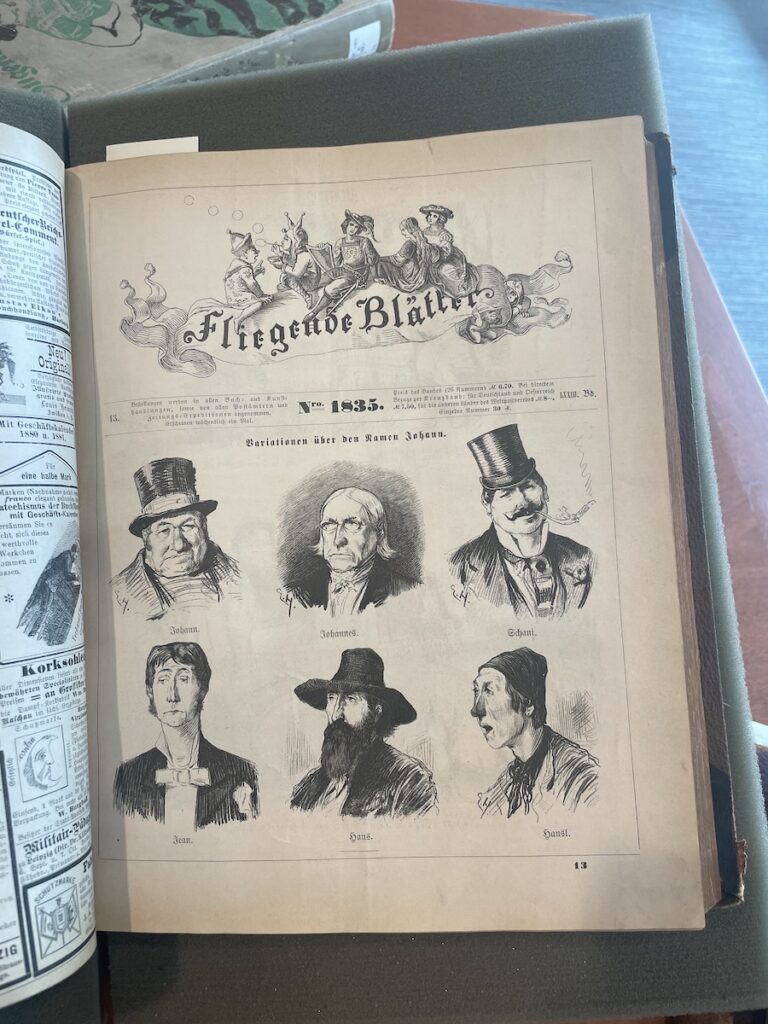

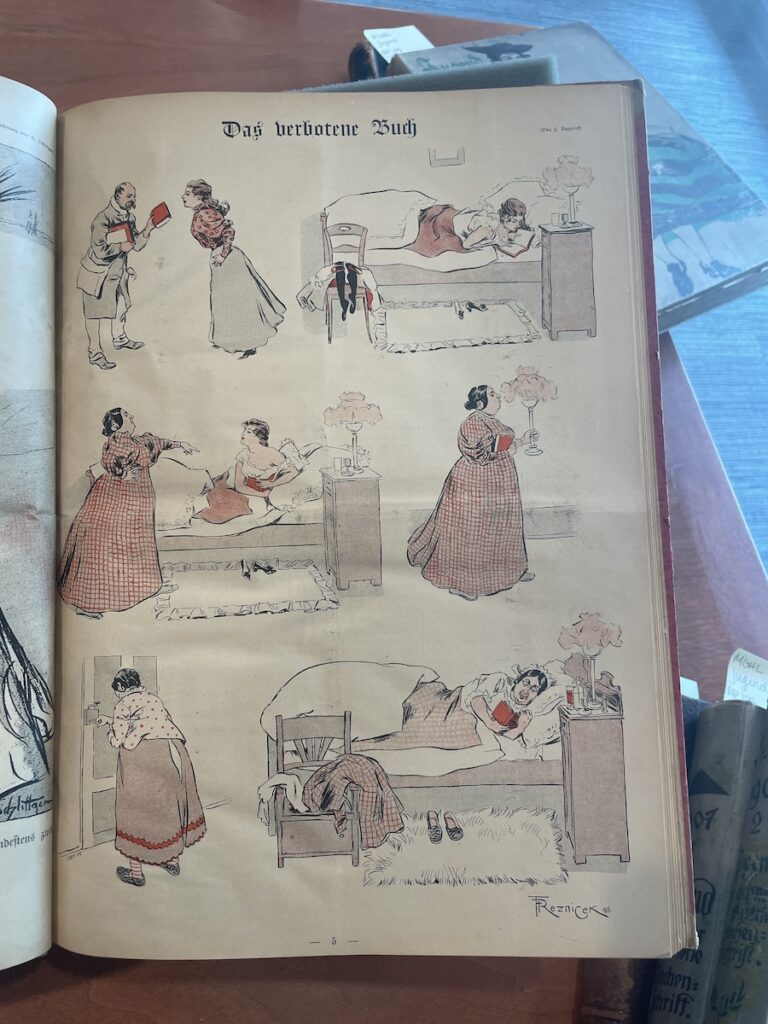

Other periodicals took a more satirical view of contemporary culture and politics, often aimed at a more bourgeois and elevated reading public than the more popular and middlebrow Gartenlaube. Fliegende Blätter appeared beginning in 1845, a few years after its similar British counterpart, Punch, created a formula mixing, humor, satire, and illustration. Poking fun at contemporary society with humorous illustrations, Fliegende Blätter reached its maximum circulation in 1895. Several issues from around the time of this peak are available in Special Collections, and digitized issues can be viewed in HathiTrust.

Illustration and Satire

As the twentieth century approached and black-and-white photographic reproductions started to appear in Über Land und Meer, Germany was also going through a renaissance of illustration, that created a new visual identity and colorful style for the era.

Jugend was founded in 1896 in Munich. The magazine’s style became synonymous with the Art Nouveau movement in Germany, and the German term for Art Nouveau even derives from the magazine’s name: Jugendstil. WashU Libraries only have a scattered run of Jugend that spans the first decade of the twentieth century, but the issues show the beauty and ingenuity of illustration from this period.

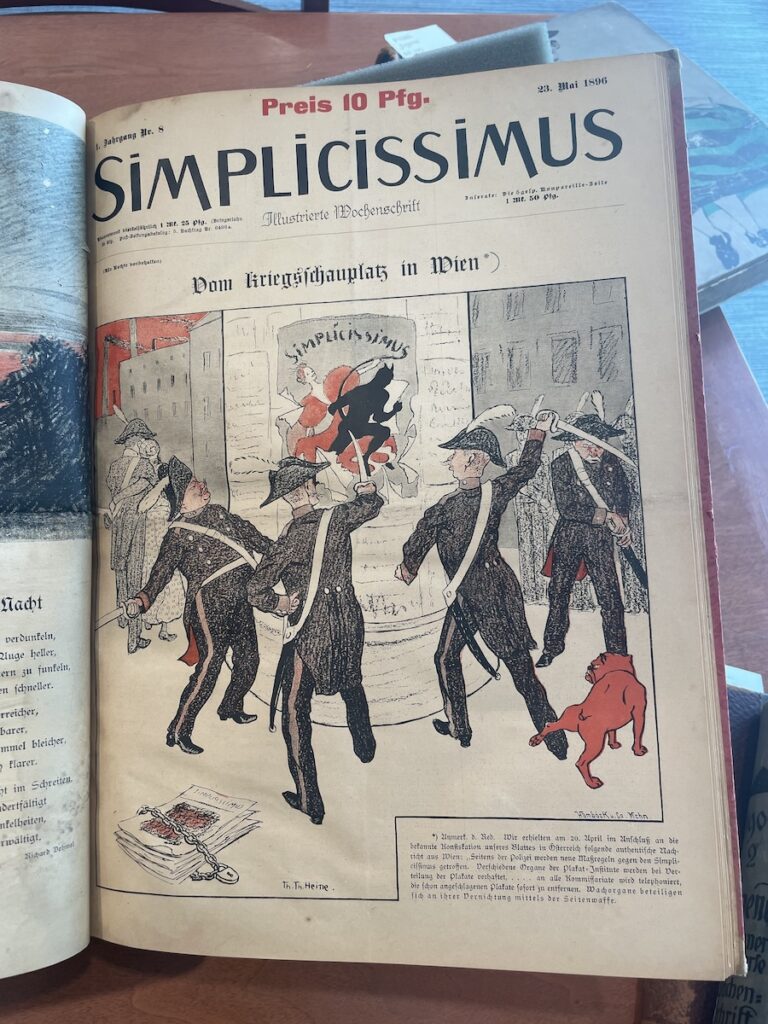

Simplicissimus was another arts and literary journal from Munich that came to define the new graphic style. It engaged in biting political satire, sometimes landing it in trouble with government censors. Its graphic style became iconic and particularly its simple and striking advertising posters had a huge influence on the development on communication design. The Libraries have a number of issues dating from 1896 to 1910. Simplicissmus and Jugend are both available digitized.

Censorship dramatically increased with the rise of the Nazis in 1933. Jewish artists, writers, and editors were fired, and these periodicals fell into decline and, for the most part, folded before the end of World War II. Postwar Germany brought on different technologies, democratic political imperatives, and new tastes that led to more modern news magazines like Der Spiegel, which was founded in 1947. Even today, German print periodicals are far from dead. You can browse current issues of Der Spiegel in the periodicals section on Level A of Olin Library.