“Worst Among Housekeepers:” Perspectives on St. Louis and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic

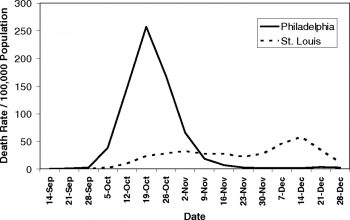

In the spring of 2020, as Covid-19 reached pandemic levels, a chart from a modern study of the 1918 influenza pandemic started circulating in popular media. St. Louis figured heavily in the article as a city that implemented early and strong measures to close schools, bars, and gatherings.

In Philadelphia, where such measures were not put in place, the rate of infection spiked, while St. Louis managed to flatten the curve of exponential infection rates. This 1918 data was used to argue for the implementation of similar measures in 2020.

People Behind the Numbers

In the spring of 1919, following the surge of influenza the previous fall, the St. Louis Tuberculosis Society formed a special committee to examine influenza statistics. The committee would help the city government understand the collected vital statistics and presumably this understanding would help inform future reforms.

Today, we can learn some useful lessons about how it can be easy to forget the real people behind the numbers.

Who Falls Ill and Dies?

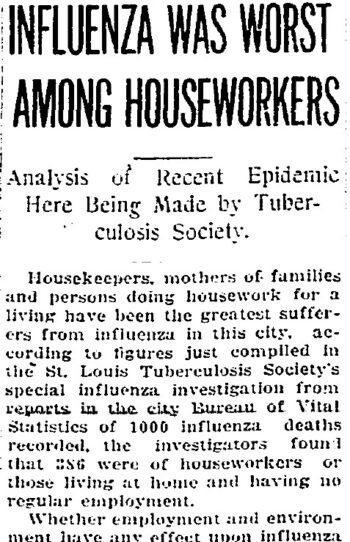

The Tuberculosis Society committee’s work was reported on February 2, 1919, in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, which noted that “housekeepers, mothers of families, and persons doing housework for a living have been the greatest sufferers from influenza in this city.” In St. Louis, “houseworkers” accounted for 386 out of 1,000 influenza deaths recorded. The next largest group was laborers, with 164 deaths.

The study also sought to determine if rates were higher in more or less crowded neighborhoods (spoiler alert: it was the more crowded ones).

Finally, the study considered if race factored into the death rate. While tuberculosis deaths in St. Louis were “four negroes to one white,” the committee found that influenza deaths were of roughly equal proportions, refuting, the committee noted, “the theory that negroes are immune.”

Takeaway Lessons

This report shows us that the largest number of deaths were among women—mothers, wives, and domestic workers. The majority of individuals who cared for sick family members at home were mothers. Jobs such as maid, laundress, nanny, and so on were almost exclusively held by women. For many African-American women in the early 20th century, these jobs were the primary work available.

Closing entertainment venues, schools, and even churches did nothing for people who provided the rest of society with food and daily essentials. Women could not avoid exposure as they cooked, cleaned, and cared for the ill. Large commercial laundries were mainly staffed by women and girls, who picked up and delivered bundles of clothes to households.

And yet, a few days after the report was published, a Post-Dispatch editorial (“One Thousand Flu Fatalities”) seemed to miss this obvious fact. Instead, the editor lamented that household workers had clearly disregarded the health department edict to “avoid crowds.” The editor’s takeaway was that “neighborly calls, domestic errands, other communications between households would appear to be important… [and] prompt isolation for their individual patient seems to be indicated as a sound preventative measure.” To the white-collar men of the editorial staff, these “domestic visits” were foolish gossip sessions that should just be avoided. Out of sight and mind were the laundry work and trips to the grocer for food.

The fact that deaths by race seemed evenly distributed between Black and white would also need more exploration. For the 1919 committee, this “equality” of death showed simply that African Americans had no special protection from the illness. Modern historians have found this pattern across the nation, and yet this does not mean there was equality between racial groups in 1918. What it shows is that without the full context, numbers alone can provide an incomplete story.

Mathematical models are one way to understand the past, and yet, when we see only numbers on a tidy chart, it can be easy to forget the people behind the numbers.

Citations

- “Influenza Worst Among Homeworkers,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1919 Feb 2, page 10

- “One Thousand ‘Flu’ Fatalities,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1919 Feb 8, page 12

- “Flatten the Curve,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flattening_the_curve (Accessed 2020 Nov 17)

- Gamble, Vanessa Northington. “”There wasn’t a lot of comforts in those days:” African Americans, public health, and the 1918 influenza epidemic.” Public health reports (Washington, D.C. : 1974) vol. 125 Suppl 3,Suppl 3 (2010): 114-22. PMID: 20568573

Explore More

If you are interested in delving into the archives for more information about St. Louis and the 1918 pandemic, you can access the Influenza Encyclopedia online for newspaper articles, vital statistics, photos, and essays about St. Louis and many other U.S. cities.

Full-text access to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch is provided by subscription through the Washington University Libraries (WUSTL Key required).

For more history related to Washington University during the 1918 influenza pandemic, consult the WWI Archives LibGuide.