Why Do Comics Get Banned?

Comic books have sparked controversy and prompted censorship for almost as long as they have existed. The most consequential case occurred in the 1950s when the psychiatrist Fredrick Wertham investigated what he saw as the negative effects of comic books on children. In his book on the topic, Seduction of the Innocent, Wertham claimed that there were direct correlations between children reading comics and juvenile delinquency. His crusade against comics led to the 1954 formation of the Comics Code Authority—a set of rules created by the publishers and distributors themselves in an effort to avoid government intervention. The code was in use in some form for the better half of the twentieth century. With the eventual suspension of the code, and with authors and illustrators pushing the creative boundaries of storytelling, comic books have been experiencing a backlash of intense criticism in recent years.

At the same time, comic books have also become increasingly visible and integrated into libraries and learning environments. This trend has made them regularly vulnerable to challenges and bans. They are denounced for all of the same content reasons that other books are, such as containing profanity, violence, sex/nudity, and drug or alcohol use. However, comics are uniquely susceptible to criticism because of the medium’s visual nature.

The purpose of the D.B. Dowd Modern Graphic History Library at Washington University Libraries is to preserve and provide access to important works of modern visual culture, including comic books and graphic novels that have been scrutinized, lauded, overlooked, and dismissed. We believe strongly that these works support the serious research of American history, culture, literature, identity and so much more. The three comics featured here are in the DMGHL’s collections and have been challenged in libraries and schools by community members. But thanks to the diligent efforts of librarians and advocates of free speech, they were ultimately kept in circulation.

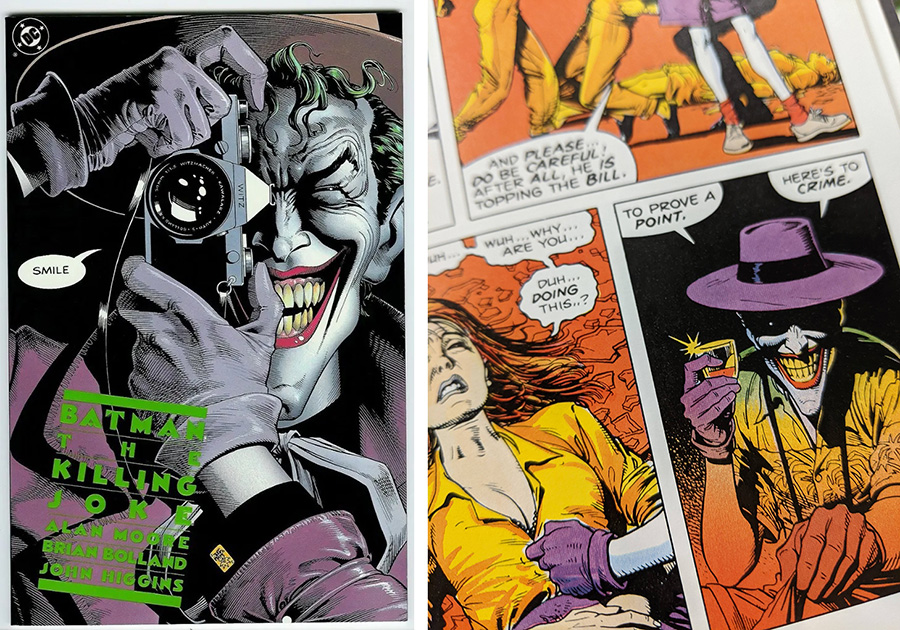

Batman: The Killing Joke, Alan Moore, Brian Bolland, John Higgins. DC Comics, 1988.

Batman: The Killing Joke is a comic that features the Joker’s violent torture of Commissioner Jim Gordon and his daughter Barbara. It is widely recognized as the Joker’s origin story. The villain’s portrayal influenced later adaptations in print and on screen, yet the story’s treatment of Barbara Gordon has been widely criticized as exploitative.

In May 2013, a patron of the public library in Columbus, Nebraska, requested that the book be removed from the collection, claiming that it “advocates rape and violence.” The challenge was brought to a library board meeting where members voted unanimously to keep the book on the shelves.

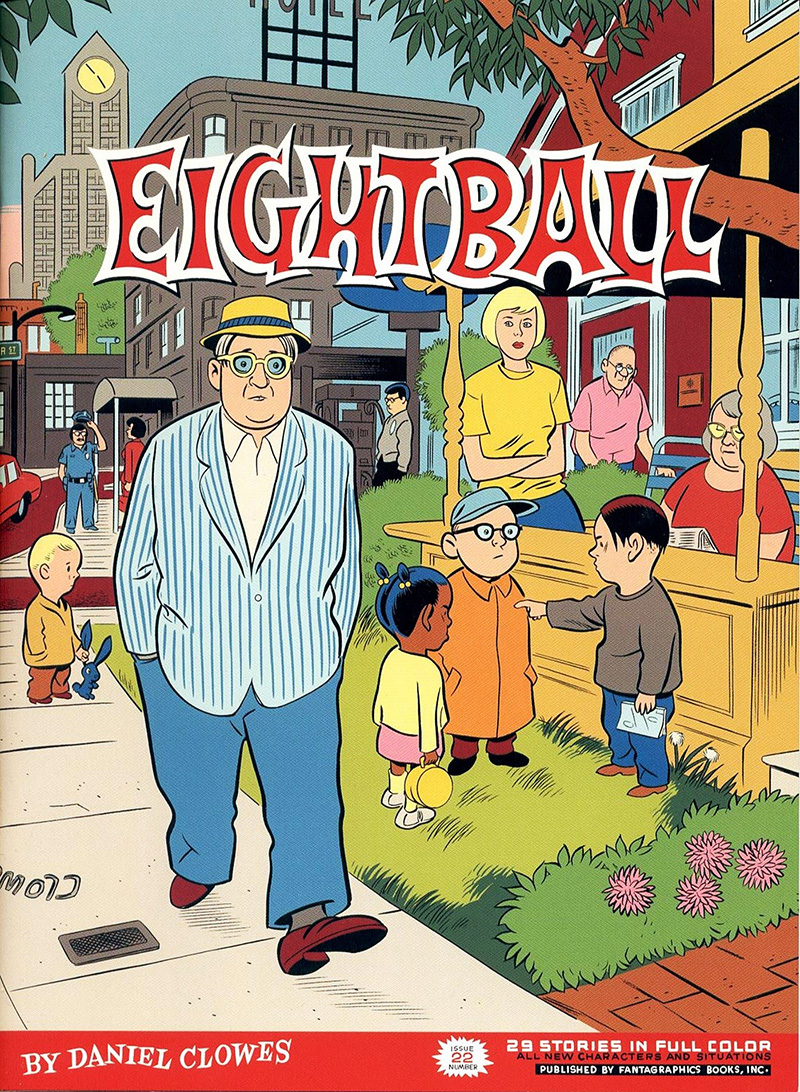

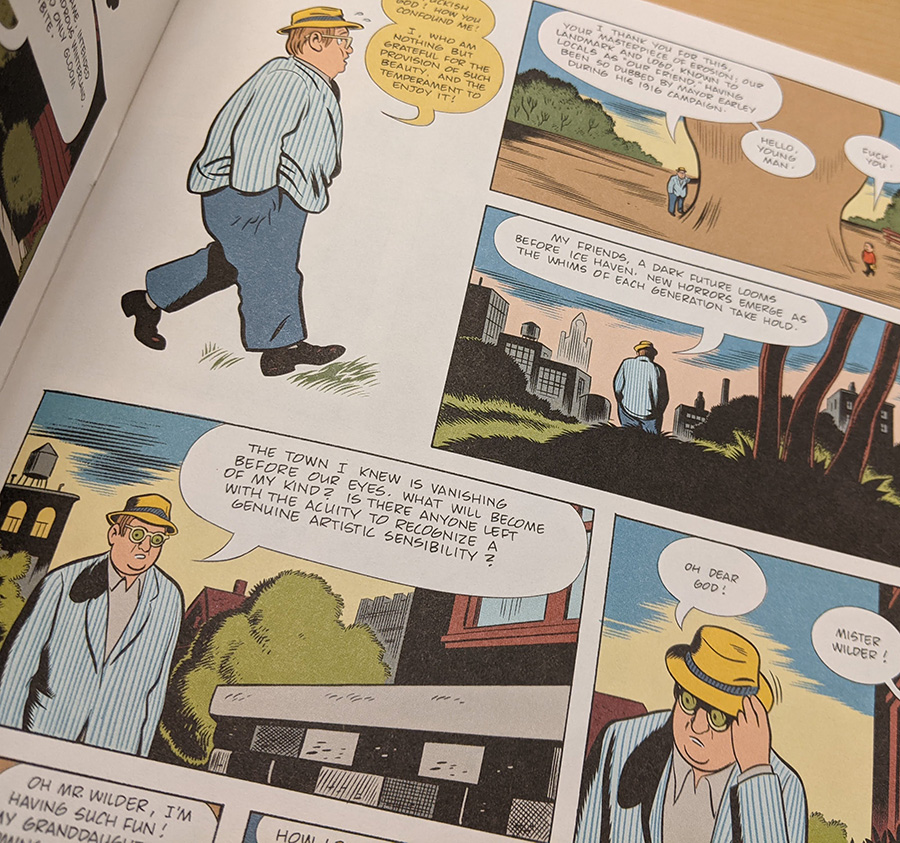

Eightball 22, “Ice Haven” by Daniel Clowes. Fantagraphics Books, 2003.

Eightball 22 contains a series of comic vignettes that together tell a story about the characters’ interrelated lives. The uniting plot line of the book describes the disappearance of a local boy named David Goldberg. The work explores the emotional lives of the small-town citizens, in a darkly humorous examination of alienation, regret, and desire.

In 2008, Guilford, Connecticut, high school teacher Nate Fisher was forced to resign from his job after a parent filed both a formal and a police complaint against him for lending a high school freshman a copy of Eightball 22. Despite the fact that Fisher resigned, investigators did not find evidence to back up claims of wrongdoing.

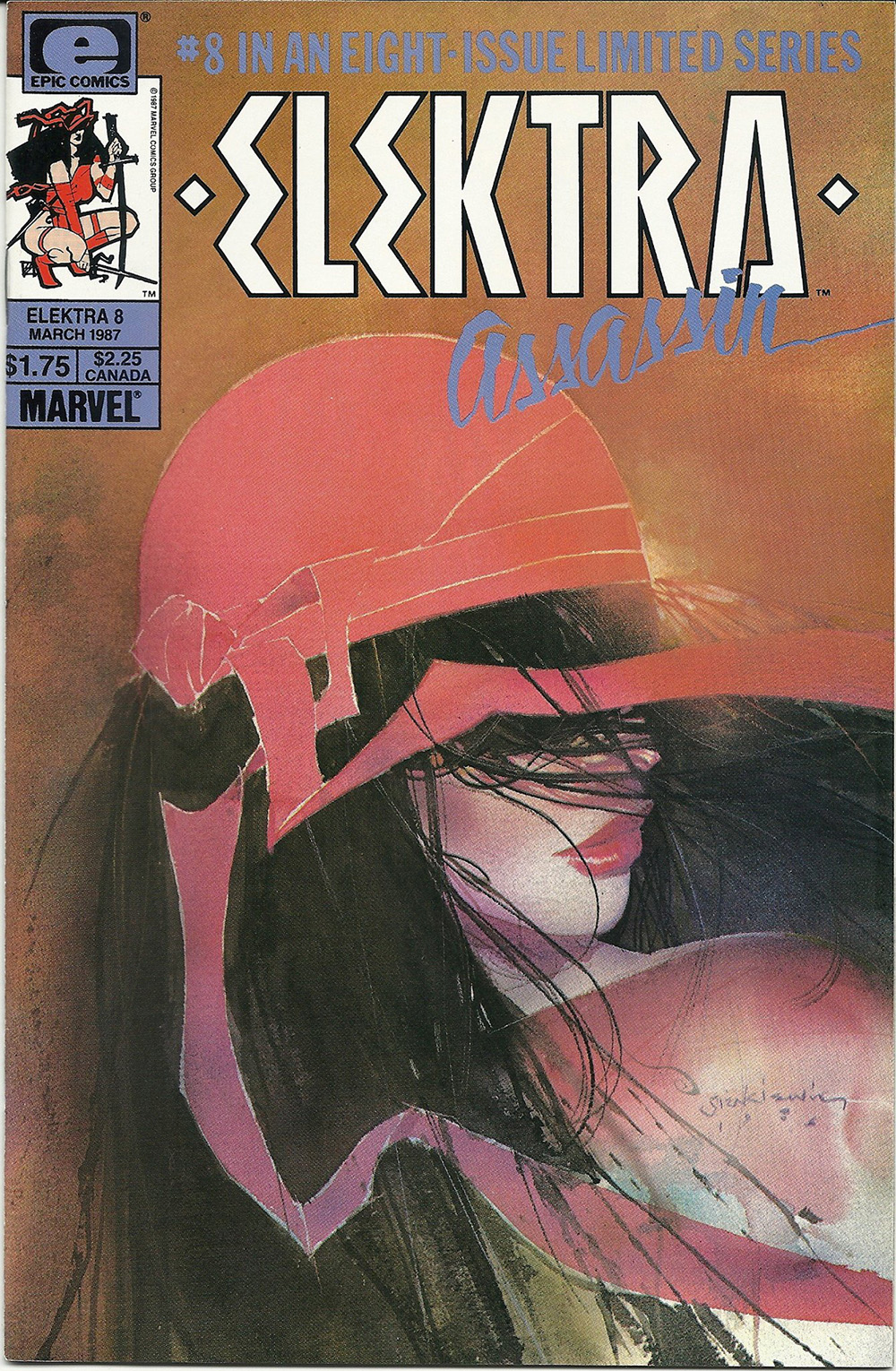

Elektra, Assassin, Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz. Marvel Comics Group, 1986-1987.

Elektra Assassin tells the story of an innocent young woman driven to a life of violence as a martial arts assassin. The series is universally known for being uniquely dark and complex and is admired for artist Bill Sienkiewicz’ experimental treatment and skillful, expressionist painting style.

Elektra Assassin found itself at the center of an obscenity case that lasted from 1986 to 1989. The display of these books in Friendly Frank’s comic book store in Lansing, Illinois, led to the arrest of its manager, Michael Correa. The works were said to be obscene and full of satanic influences. Correa was found guilty of obscenity, but the verdict was later overturned by an appeals court. The incident led to the formation of the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, which protects the First Amendment rights of comics and its community of retailers, creators, publishers, librarians, and readers.

All images courtesy the D.B. Dowd Modern Graphic History Library, Department of Special Collections, Washington University Libraries.

The article was originally published by the Center for the Humanities at Washington University.