Where Was That? : Using Travel Guides to Reconstruct LGBTQ History

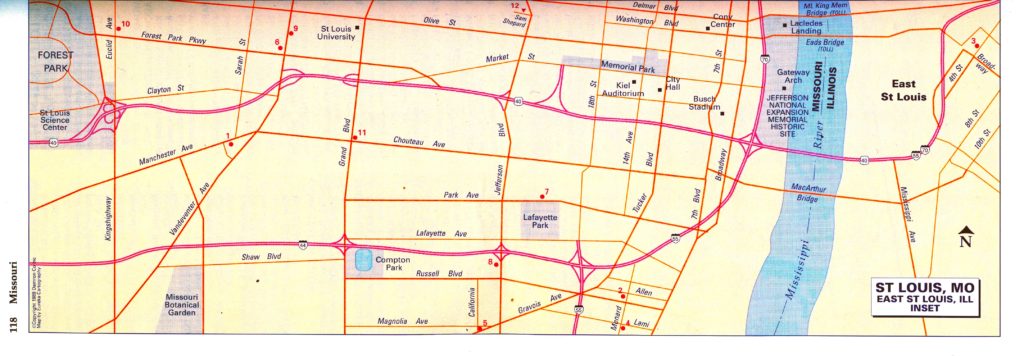

A key challenge as we researched Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis was locating street addresses. Since many bars and restaurants were well known to locals, our researchers often found only vague references to places, such as “PK’s across the river” or “Betty’s on the south side.” Few people now, let alone from 30 years ago, remember the street address of their favorite bar. However, Graphical Information Systems (GIS) need precise data — a street address or intersection of cross-streets, city, state, and zip code.

Enter the Travel Guides

A key source for this specific data were small guidebooks originally published for gay and lesbian travelers. These books functioned in a similar way to the Green Book which helped African-American travelers find welcoming hotels, restaurants, and services in the 1930s-1960s. While no one source of information provides an accurate picture of the past, for anyone conducting a mapping or place-based history of LGBTQ life in the USA, travel guides are an invaluable and highly recommended source of data.

Damron’s Legacy

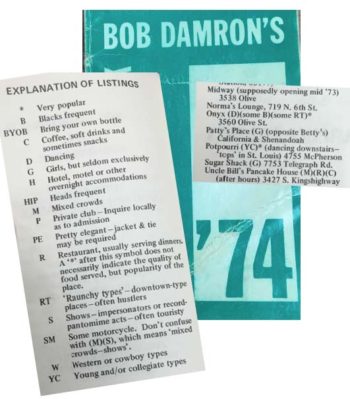

In 1964 Bob Damron’s Address Book became the first published yearly directory listing establishments frequented by and friendly to gay men. The concept was popular and often copied by other publishers. Online access to digitized copies at the ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archive in California is available at the library via the LGBT Thought and Culture database (on-campus or proxy login required). The St. Louis LGBT History Project also provided PDF copies of the illustrated Damron Travel Atlas.

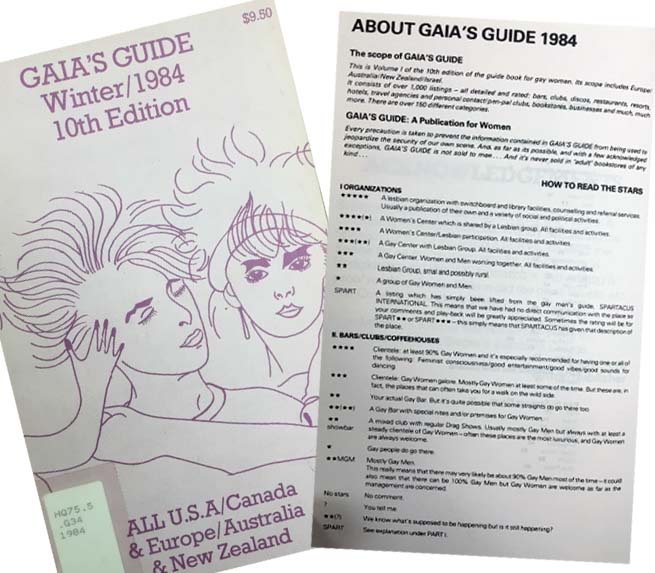

Courtesy of the Gerber/Heart Archives in Chicago, we received PDF copies of pages for Missouri and Illinois (excepting Chicago) for the Guild Guide (1965, 1968, 1970), Eros Gay Guide (1974), and Gaia’s Guide (1977 – 1992). These first two were direct competitors to Damron. The latter, Gaia’s, focused on locations of interest to lesbians, including identifying women-only spaces.

From Guide to Data

The guides are organized by city, so locating our needed street addresses was fairly simple. They are yearly, allowing us to determine when a bar or tavern was in operation. They also had errors, which we discovered as data was compiled and entered into the spreadsheets. Most commonly, the location would continue to be included in the next year’s book, despite closing. In a few cases, there were just mistakes — such as several years of Damrons listing “Betty’s” at Shenandoah and Compton, several blocks away from the correct location at cross-streets Shenandoah and California. In these cases, we relied on newspaper accounts, telephone book listings, and oral histories to confirm the correct data.

Adding Context

We carefully evaluated the descriptions and classifications provided in the guides. Publishers used an elaborate system of codes to indicate the type of people, activities, and general atmosphere travelers would encounter. Since the publishers presumed the majority of readers would be white, race was only indicated if a place had African-American patrons. Similarly, while Damron did include some mentions of bars “popular with girls” it was, until the 1990s, directed at a male (white) reader. And complicating this were yearly changes to the meaning of abbreviations and stars.

Deeply considering the meaning of what was, and was not, listed in these descriptions allowed us to extrapolate even further data.

Look for announcements and updates about the project on our Mapping LGBTQ St. Louis blog.

Questions or looking for more information about the project? Email Miranda Rectenwald (mrectenwald@wustl.edu).