Gardner and Gass: A Friendship in Letters

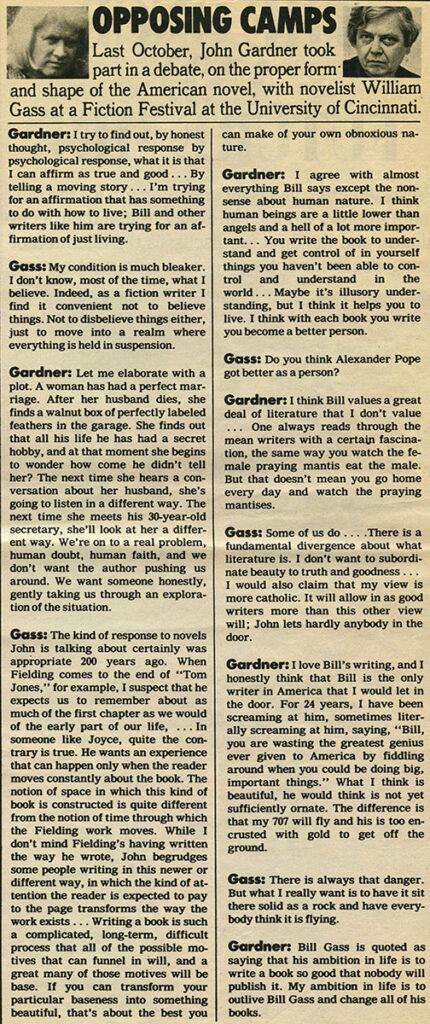

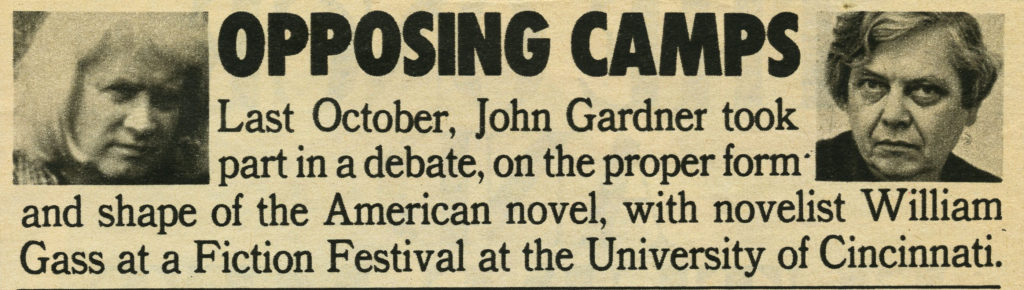

On the evening of October 24, 1978, William H. Gass and John Gardner stepped onto a stage at the University of Cincinnati. For two hours they held forth in debate on a topic close to the heart of both men: the nature and purposes of fiction. Those in attendance, and those reading and listening later, would be forgiven the impression of two passionate enemies facing off in anger with the fate of the soul of fiction hanging in the balance, but this would be far from the truth. What’s really being witnessed in this debate is the late stage of a long-running conversation between two friends who happened to disagree about some finer points of fiction and philosophy: Gardner believing that the aesthetic excellence in a work arose from its support of true moral values, and Gass that aesthetic beauty was a high value in and of itself. While this formulation is a grossly reductive simplification, it serves to illustrate the basic principles that led Gass to write the reviews and essays establishing “metafiction”–first and foremost in the 1970 collection, Fiction and the Figures of Life–and Gardner to write the 1978 book On Moral Fiction, largely in response to this new literary genre and all its practitioners.

Audio recordings of Garnder and Gass’ October 27, 1978, discussion are available through the University of Cincinnati. To get some of the highlights, see our scan of the following clipping from the William H. Gass Papers:

Though one might expect writers with such divergent philosophies to dislike each other’s work, the truth is Gass and Gardner formed something of a mutual admiration society. In just one example, Gass wrote of Gardner’s second published novel, that “The Wreckage of Agathon is one of the finest contemporary fictions.” For Gardner’s part, his often direct and scathing critiques of other writers often left some room to spare Gass–or at least to critique Gass’ philosophy while praising his fiction. He specifically credits Gass in the acknowledgments page of On Moral Fiction as someone who inspired some of the ideas in his book by being someone with whom he “usually disagrees.” In the debate clipping above, Gardner says he loves Gass’s writing “and honestly think Bill is the only writer in America that I would let in the door.”

John Gardner’s papers are primarily held by the University of Rochester, though his materials do appear in various holdings of the Modern Literature Collection, including The Lord John Press Collection. Gardner had a long association with Washington University, where he received his BA in 1955, and where he wrote, for Jarvis Thurston’s fiction class, the first stories that would eventually become his 1973 novel Nickel Mountain. His ongoing association with Gass and Thurston, as well as Donald Finkel, Mona Van Duyn, and Stanley Elkin, produced a wealth of correspondence, which is held in their respective papers. Perhaps most illustrative are Gardner’s letters to Gass, which offer a portrait of literary friendship in the best sense of both words, by turns admiring, playful, jovial, and cutting.

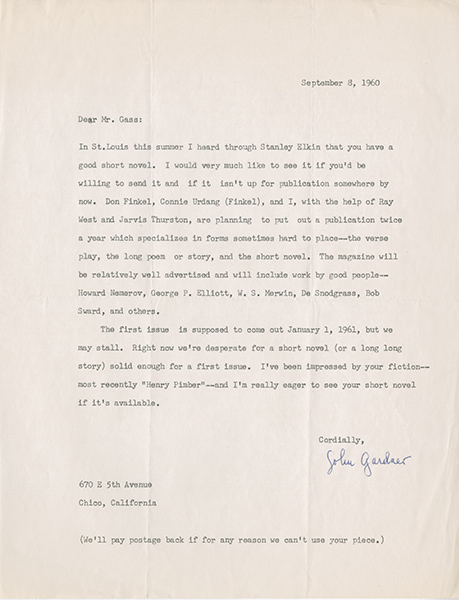

The two seem to have first come in contact when Gardner sent this request for a short novel he’d heard Gass had written, to publish in the first issue of his upcoming literary journal MSS (the letter also mentions other present and future Washington University writers involved with or being published by MSS–Elkin, Finkel, Urdang, Thurston, Nemerov, Elliott, Sward):

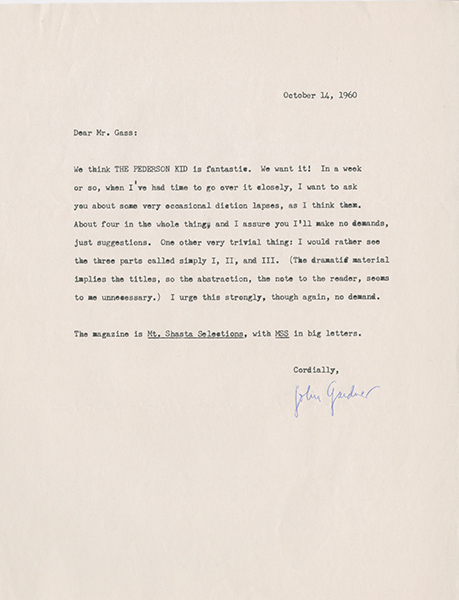

The story Gass provided, “The Pedersen Kid,” was enthusiastically received, as shown in the following letter. Gardner would frequently refer to it as a favorite story in coming years.

Unfortunately, The Pedersen Kid became the downfall for MSS. It was forced to cease publication in 1964, after only three issues, under the threat of a lawsuit by the United States Post Office on thirty charges of obscenity counts for publication of the story–including, amazingly, use of the word “nape.” The magazine could not afford the burden of the fines.

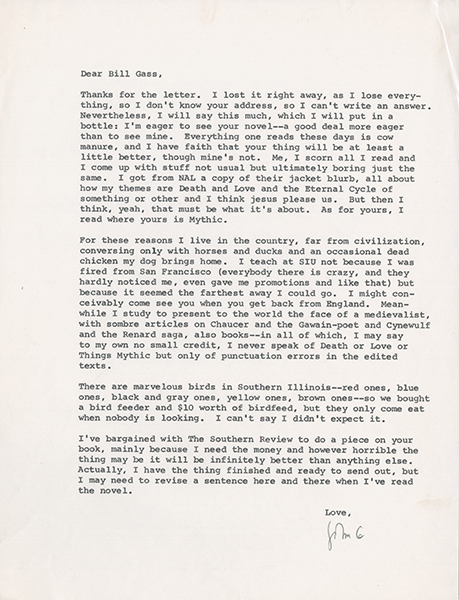

Later letters reveal a burgeoning and trusting friendship, with Gardner alternating self-deprecation for his own works—in this instance referring to the jacket blurb for The Resurrection, as well as a novel-in-progress that may be The Wreckage of Agathon or The Sunlight Dialogues— with praise for Gass. In the following letter Gardner (addressing it to “Bill Gass” rather than “Mr. Gass”) is anticipating the publication of Omensetter’s Luck, and peppers his missive with a kind of rural pastoral whimsy, as he has just moved to the country in Southern Illinois:

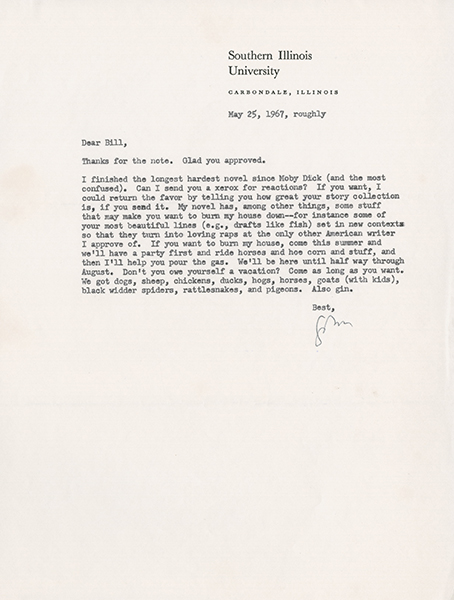

Gardner, known for being direct and unsparing in his criticism of others, was also unafraid to solicit criticism of his own work, as long as it came from someone whose skill and taste he admired. Due to Gardner’s idiosyncratic working habits, often writing several novels simultaneously for years before publication, it’s difficult to tell in the following letter (now addressed to simply “Bill”) which novel he’s asking Gass to read, though his description of its length and ambitions suggests The Sunlight Dialogues, which would not be published until 1972.

The letter also highlights another of Gardner’s literary techniques, that of re-purposing the writing of others in new contexts, in this case a piece of description from Gass’ The Pedersen Kid, collected in In The Heart of the Heart of the Country (1968), which Gardner praises in the letter. He admits to Gass that he took “some of your most beautiful lines…set in new contexts so that they turn into loving raps at the only other American writer I approve of.” In typical humorous fashion, he invites Gass to vacation on his farm before Gass (with Gardner’s help) burns Gardner’s house down, as a sort of revenge.

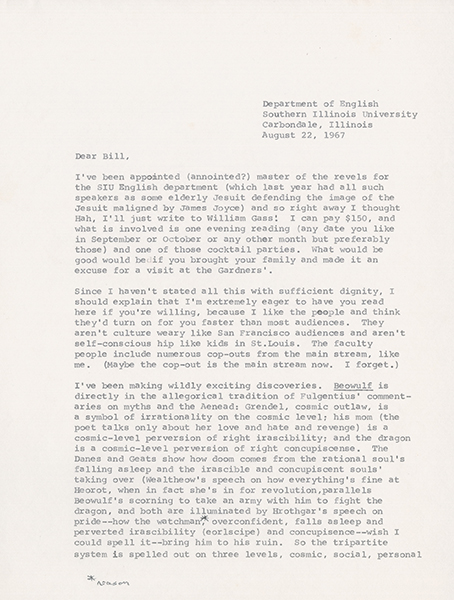

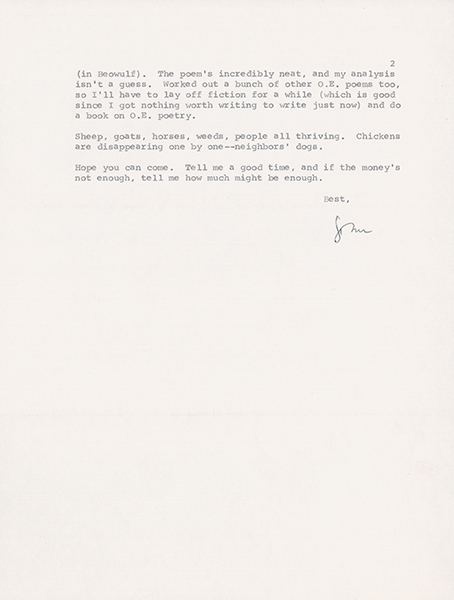

By August 1967 Gardner had been placed in charge of securing the visiting readers for the Southern Illinois University-Carbondale English Department, and he used the opportunity to invite Gass to speak. The letter also contains an explanation of Gardner’s ideas on the philosophical underpinnings Beowulf, which reads like an outline for what would become Gardner’s breakthrough 1971 novel Grendel, a retelling of the Anglo Saxon epic through the eyes of its monstrous villain.

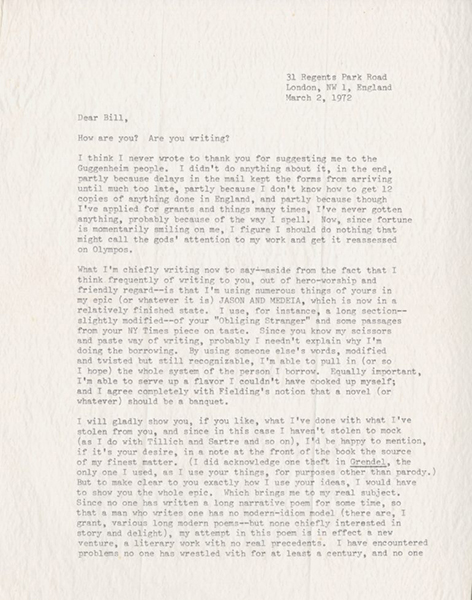

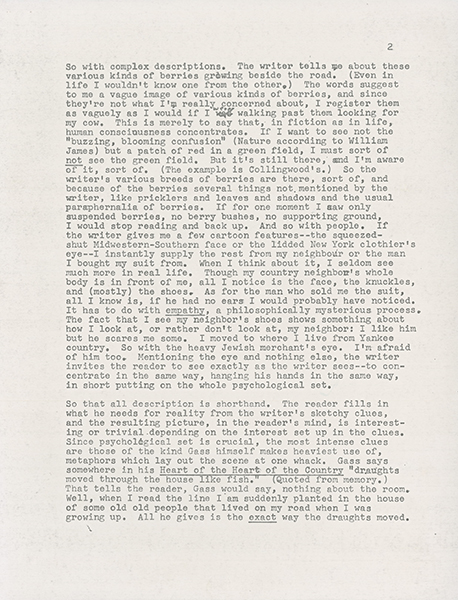

The following letter, from 1972, finds Gardner thanking Gass for “suggesting me to the Guggenheim people.” He then solicits Gass for input on an ambitious text, an epic verse poem, Jason and Medea, which in addition to adapting The Argonautica of Appollonius Rhodius and Euripides, appears again to incorporate reworked elements of Gass’ essays and journalism.

On the second page of the letter, Gardner admits he only has “small objections” to Gass’s literary theory, and that Gass and John Barth are establishing “a whole new direction for literature.” He is speaking of fiction when he observes, “The only way left open to true nobility is the way of the serious clown,” and later cites Omensetter’s Luck as the ultimate example of this. He declares the “evil of modern poetry…is that it took itself too seriously.” However, he still believes in realism, even if Gass does not. Thus, Gardner is out to “destroy the whole effect of Pound and Eliot” and write the new Arabian Nights for housewives, mathematicians and philosophers alike. One must admire his ambition, if nothing else.

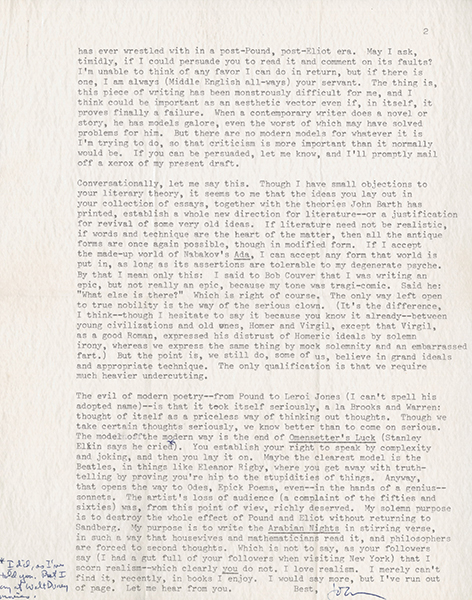

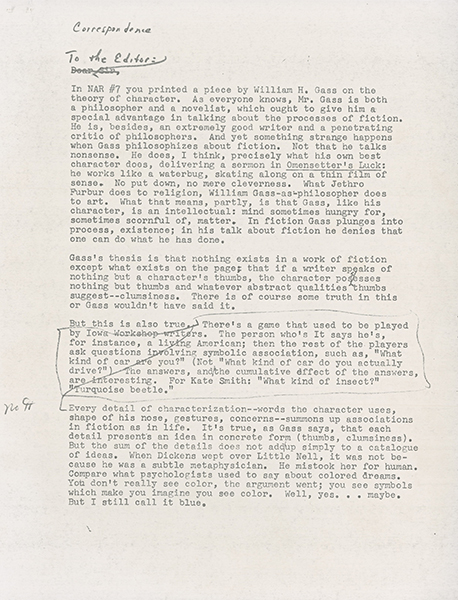

But friendship with Gardner and requests for favors did not exempt Gass from public criticism when Gardner thought he had gone astray, as demonstrated in this long letter to the Editor of the New American Review in response to a piece Gass had published there on the topic of character. Much as in their later public debates, Gardner engages in a vigorous refutation of what he sees as misguided in Gass’ thinking about fiction, while just as vigorously championing his gifts as a writer of fiction. Perhaps it’s a testament to their friendship that Gardner sent Gass a copy of the draft.

Gardner’s letters to Gass demonstrate a true friendship which never flagged, whatever their disagreements in public or in private. Listening to the recording of their 1978 debate you get a sense that the conversation could have continued for many more hours, if it wouldn’t have interfered with a reading Gardner was scheduled to give. In fact, one gets the impression that if these two writers were still with us, their debates still be going today. Mary Gass, Bill’s widow, tells us when Gardner visited St. Louis he and Gass would stay up until the wee hours of the morning, debating these very matters in private, over drinks. If only they had a recorded those conversations too! Sadly, Gardner died in a motorcycle accident in 1982, just as he was publishing his short-lived MSS journal again, this time at SUNY Binghampton.

The Department of Special Collections will be hosting a screening of Sunlight Man, a documentary on John Gardner, on Thursday, March 29, 2018, at 5:30 pm in Wilson Hall, preceded by an Open House in Olin Library at 4:00 pm.

The University will be hosting a tribute to William H. Gass on Friday, April 6, 2018, in Special Collections in Olin Library and in Holmes Lounge.

The materials in this post are taken from The William H. Gass Papers in the Modern Literature Collection. Unfortunately, Gass did not keep carbons of any letters he may have written to Gardner, and only one such letter shows up in a search of the online database of Gardner correspondence at the University of Rochester. They are also not present in the John C. Gardner Papers at SIU-Carbondale. See the link in the opening paragraph of this post to listen to the debate at the University of Cincinnati.

The information on MSS was taken from “John Gardner and MSS” by L.M. Rosenberg, The Missouri Review, Volume 7, Number 1, Fall 1983.