‘Liberating the Spoken Word Project’ Gives New Life to Rare Poetry Recordings

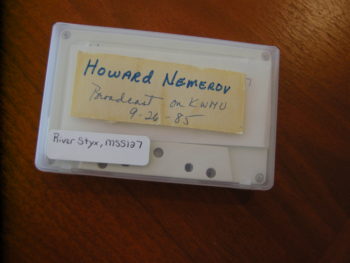

The National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) has awarded a grant of $34,433 to WU Libraries to fund the project “Liberating the Spoken Word: Poetry Readings and Literary Performances in St. Louis, 1969-2005.” The grant will allow the Libraries to digitize and create metadata for 947 audio recordings from three archival collections: the River Styx Archive, the Jan Garden Castro Papers, and the Michael Castro Papers. Selected recordings will be made available online.

During the late 1960s and early ’70s, WU alum Michael Castro, St. Louis’s first poet laureate, and Jan Garden Castro, a noted author and arts activist, were instrumental in starting the River Styx Poets radio show and the literary journal River Styx. They also helped establish St. Louis’s renowned River Styx poetry series, a program of regular public readings by prominent regional, national, and international writers, with an emphasis on diversity.

Held at Duff’s Restaurant, the monthly readings featured guests such as South African poet Dennis Brutus and Native American writer Joy Harjo, as well as a host of local poets. A second program, the River Styx PM reading series, which started in 1981, featured the likes of James Baldwin, Adrienne Rich, Robert Bly, and Margaret Atwood. More than 700 poets were recorded through the radio show and reading series.

A wealth of archival material connected to the literary organization can be found in the River Styx Archive, the Jan Garden Castro Papers, and the Michael Castro Papers, which are housed in the Manuscripts unit of Special Collections at WU Libraries. The collections contain small-press publications, correspondence, and ephemera, as well as audio recordings, and provide an intriguing overview of St. Louis literary history.

A classic collection enters the digital age

The NHPRC awards funding each year to select archival projects. WU Libraries’ were one of seven institutions selected for a grant from a pool of 48 applicants. The two-year grant started on March 1.

“The funding from the grant will allow us to provide complete public access for the first time to the recorded River Styx performances,” says Joel Minor, curator of the Modern Literature Collection and Manuscripts at WashU Libraries. “The recordings will deliver the authentic, immediate experience of hearing some of the most important literary voices of our times perform their own work.”

The recordings include cassettes and reel-to-reel tapes, most of which are in good condition. Minor believes that 60 percent of them consist of poetry and literary performances. Migrating the recordings to digital format through an outside vendor will take between four to six months. Quality checks and metadata creation—identifying who’s on the tape, and when it was recorded—will follow. Additionally, about 2,300 leaves of ancillary materials—flyers, letters, and other paper items—will be scanned and made accessible online to complement the listening experience.

The digitized performances and accompanying ephemera should be available via Washington University’s Digital Gateway by March 2019. Enhanced finding aids and complete metadata for all 947 recordings will also be available online.

A conversation with Michael Castro, St. Louis’s first Poet Laureate

Michael Castro lives by this rule: Never read your poetry unasked. If asked, never refuse. He can’t recall where he came upon these words of wisdom—in a fortune cookie, maybe, or the Analects of Confucius—but the concept made a lasting impression.

For Castro, the invitations to read have been on the upswing since 2014, when he made St. Louis history by being selected to serve as the city’s first poet laureate. A beloved figure in local literary circles, he was chosen from a pool of 64 candidates in a unanimous vote by the City of St. Louis Poet Laureate Taskforce. He was officially inaugurated to the two-year post on January 31, 2015, in a ceremony at the Regional Arts Commission.

From the early immersion in Native American cultures that led to his groundbreaking book Interpreting the Indian: 20th Century Poets and the Native American (1983) to more than four decades of teaching, translating, and composing poetry (not to mention a brief stint in the ‘70s as secretary to Allen Ginsberg, with whom he collaborated on a poem), Castro’s past primed him for the position of poet laureate. He came to St. Louis from his native New York in 1967 to attend Washington University, earning a doctorate in American literature. He went on to teach at the University of Missouri-St. Louis and Lindenwood University.

He was an early advocate for diversity. In the 1970s, Castro helped shape the arts scene as a co-founder of River Styx, a St. Louis-based literary organization that promoted multiculturalism before the term was in use and advocated for an inclusive approach to poetry. The group put out the first issue of its award-winning journal, River Styx, in 1975 and is still publishing today.

During his 32-year tenure at Lindenwood, Castro established the MFA program in creative writing. Now 71, he has published ten verse collections. His tenure as poet laureate ended in January, but he continues to act as a sort of literary prime minister for the city of St. Louis, speaking at civic events and mentoring aspiring writers.

Acclaimed poet and St. Louis native Eugene Redmond, who has known Castro for 50 years, spoke at his inauguration in 2015. “Michael Castro has no equal in this country for his service to poetry and poets,” Redmond said. “Wherever poetry can grow, you’ll find Michael Castro.”

The Washington University Libraries sat down with the poet for a Q-and-A.

Interviewer: You moved to St. Louis in 1967 to attend Washington University and never left. How has the city influenced you and your work?

MC: One influence has been my exposure to all of the wonderful music here in St. Louis. Over the years, I’ve done a lot of performing with jazz musicians, and as a result, the rhythms of jazz and the notion of improvisation are central to my poetry. The foundation of listening, which is important in jazz, is also important with my poetry. I’ve been fortunate to be associated with many great musicians in St. Louis who are open to poetry and really get it.

You’ve been involved in the St. Louis poetry scene for about five decades. How has the literary landscape changed over the years?

When I was a grad student here in the 1960s, I found that the only readings taking place were in academic settings, and they were staid, dull affairs. So I started meeting with other young poets and sharing work, and that’s how River Styx came to be. We started the River Styx radio program with the notion that poetry should have a wider audience and not be limited to academics.

We also encouraged diversity and multiculturalism. Our readings were highly charged, electric events with energy. With music. We believed poetry could bridge diverse readers and audiences and could be a rich experience, and our model spread all over St. Louis. Today most readings don’t take place on university campuses. They’re held at coffee shops and community centers. They’re community-based events, and the people who attend—to read or to listen—are a more diverse group. River Styx pioneered these types of readings in St. Louis.

Could you comment on the potential of poetry—and of the poet—to act as a social force, to create connections and serve as a unifying influence, in light of divisive events like the 2016 presidential election?

Poetry can’t solve problems, but it can work as a consciousness raiser and put people on the same wavelength. It can have a ripple effect, spreading the ideas that need to be spread to produce healthy change. As a poet, I often write about social issues, and unity is a theme that dominates my work. But I respect many poets whose work is more hermetic, because that, too, establishes unity, by taking the reader out of the prison of his own consciousness and establishing a connection, which is very healthy and very important.

What were your goals as poet laureate? Do you feel that you were able to achieve them?

My goals have been to promote the art of poetry, to unify the poetry communities, to expose poets to new audiences and new audiences to them. Another goal was to contribute to the healing process in the region in the wake of the killing of Michael Brown.

I think I’ve been successful in promoting the art of poetry. I’ve made over 100 appearances in the past two years and launched two reading series with the help of the Unity Community team [a group of regional writers, curators, artists, and organizers] I’ve assembled. In 2016, the five-day St. Louis Brick City Poetry Festival featured Missouri’s poet laureate, Aliki Barnstone, St. Louis’s first youth poet laureate, Bisa Adero, and the poet laureate of the United States, Juan Felipe Herrera. We’ve held readings in the Old North neighborhood, the Central West End, the Cherokee neighborhood, Maplewood, East St. Louis, and University City. All of these events have promoted the Unity Community theme. We’re still working on the healing of the region.

More and more U.S. cities are appointing poets laureate. What do you think is spurring this trend?

There’s a reason that poets have been called the unacknowledged legislators of mankind. Institutions are objective, and poets are subjective—they interpret, they bridge gaps and build connections. I think that poets can provide an in, they can penetrate communities and populations that might otherwise be off-limits. They can build trust, raise consciousness—political and otherwise—and open people to an awareness of the unity of humanity and all levels of life.

What writing projects are you working on now?

I’ve got a manuscript close to completion that deals with my heritage as a Sephardic Jew, and I’ve put together a collection of selected poems from 1970-2016 that will be published this year by Singing Bone Press. A collection of Sephardic proverbs that I’ve gathered and in some cases translated will also be published this year, by Coolway Press. I have journals going back to 1969 that have made me think of doing a memoir. They’re a little sporadic but pretty representative of the times. I have a lot of raw material to work with. I’ll just keep on trucking.