Norman Rockwell and Race: Complicating Rockwell’s Legacy

If you were to ask someone today what they think of when they hear “Norman Rockwell”, their answer will most likely involve simplicity, sentimentality, and “traditional” American values. They might even mention his highly famous “Thanksgiving picture” (more formally known as “Freedom from Want”), one of his most well-known paintings and a piece that effectively illustrates the nostalgic sentimentality for which Rockwell is best remembered.

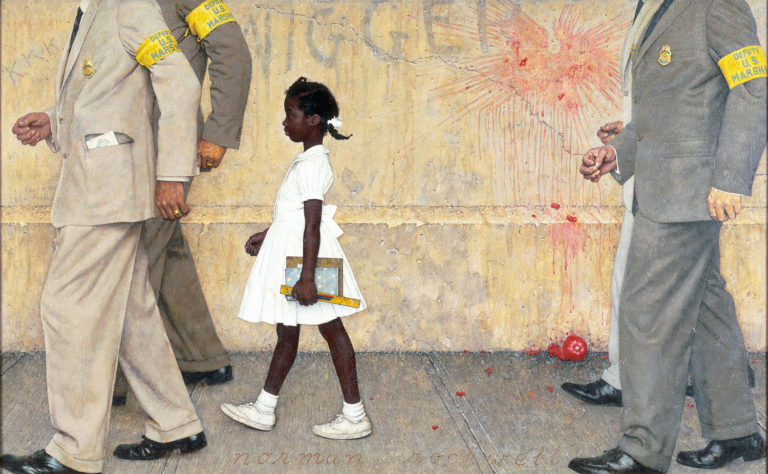

However, it’s unlikely that many people would mention Rockwell’s equally seminal painting, “The Problem We All Live With”, in which a 6-year-old Ruby Bridges and a team of U.S. Marshals walk past walls covered in thrown vegetables and racial slurs on their way to her first day of classes at an integrated school.

Race, and specifically issues of racial discrimination and violence, are not commonly associated with our contemporary understanding of what is “Rockwellian”, but perhaps they should be.

As one of the best-known illustrators of the 20th century, Norman Rockwell has come to occupy a very specific space within modern America’s collective memory. While Rockwell’s name is most-often evoked as a symbol of an idealized, conservative, white American past, looking at Rockwell’s actual career reveals a more complicated truth. The evolution of Rockwell’s depictions of race over the course his career demonstrates not only changes within his own personal ideology, but changes within American culture itself.

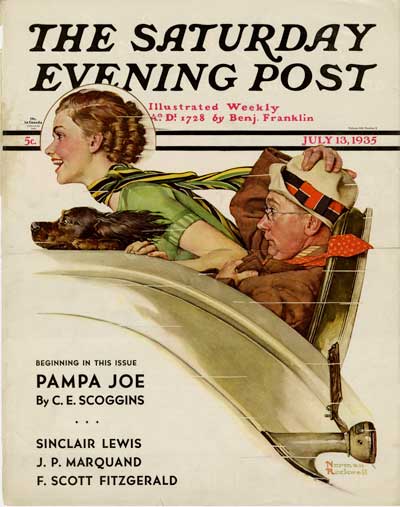

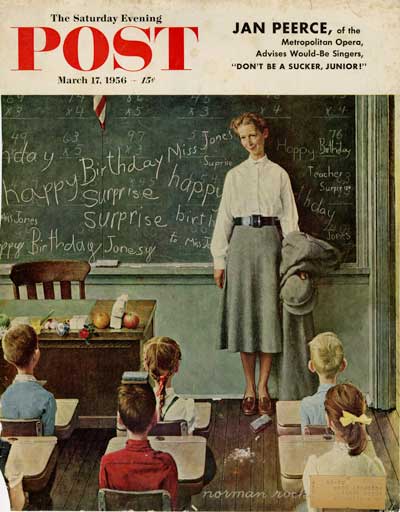

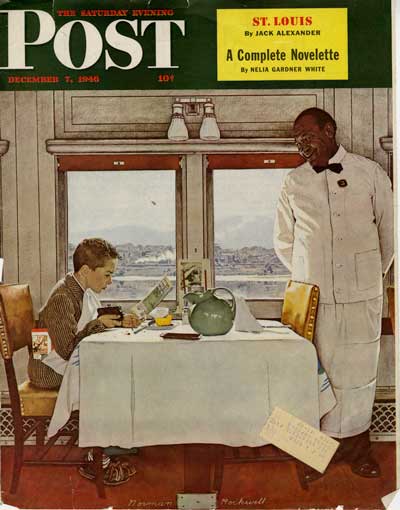

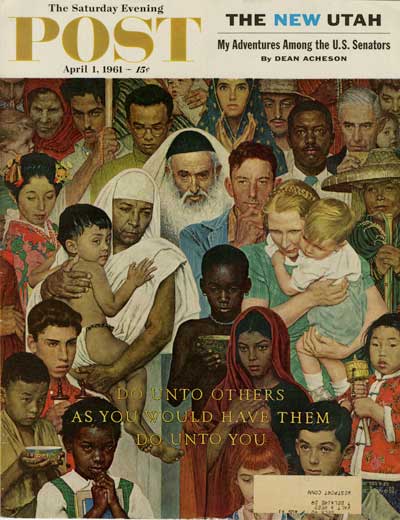

In 1916, Rockwell started working as a cover illustrator for The Saturday Evening Post, a position that he held for nearly 50 years. During his time with the Post, Rockwell became famous for his sentimental portraits of American life, and his covers depicted a simpler, more wholesome version of America. However, it is important to note who was missing from these illustrations. Due to the rules of the Post, Rockwell’s America was almost exclusively white, and minorities were only represented if they were in servile positions. While the Post seemed to relax their rules a bit by the 1960s, publishing Rockwell’s multi-ethnic “Do Unto Others” cover in 1961, their pace of change was not quick enough. In 1963, Rockwell traded his position at the Post for one at Look magazine, a publication that was more comfortable discussing and illustrating the racial realities of the time.

Typical Post covers illustrated by Norman Rockwell over the years:

One of the few images of an African-American by Rockwell while he was working at the Post. This cover demonstrates the “servile position” requirement of representations of minorities:

Rare illustration of ethnic and racial minorities in non-servile positions on cover of Post, April 1 1961:

It is clear that Rockwell was deeply affected by the racial violence of the day, and it was his move to Look magazine that finally allowed him to publish artwork that responded to these racial realities. His most famous work for Look magazine was also one of his first, and was published in 1964, a year after he started working at the magazine. “The Problem We All Live With” – a painting so powerful that President Obama requested it for the White House in 2011 – effectively illustrates both the progress of, and resistance to, the Civil Rights Movement, and serves as a clear departure from Rockwell’s previous depictions of race.

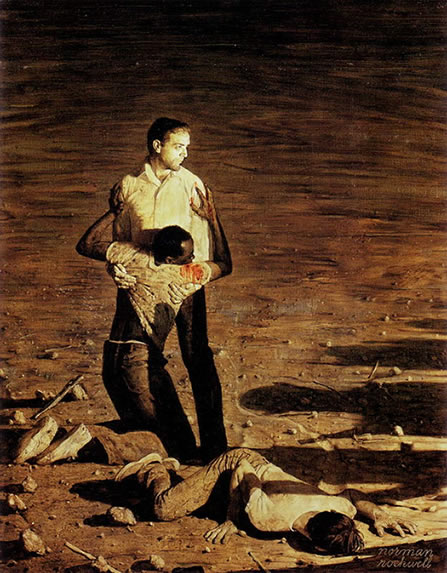

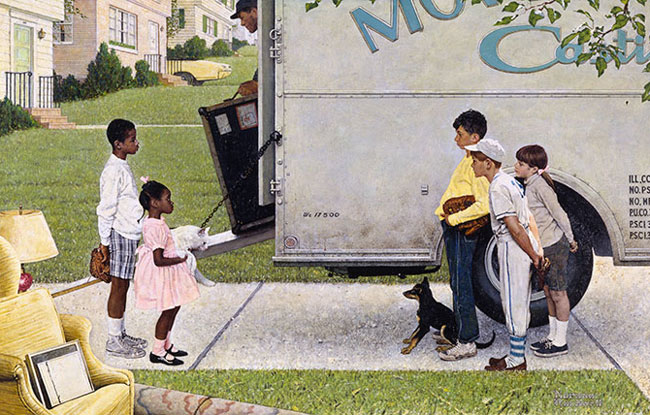

Look continued to encourage Rockwell’s exploration of racial issues, and over the next four years, Rockwell produced two more illustrations that tackled racial tension and violence head-on. “Southern Justice”, published in 1965, was painted in response to the murder of three civil rights workers in Mississippi a year prior, and is one of Rockwell’s darkest and most striking pieces. “New Kids in the Neighborhood”, published in 1967, uses black and white children to highlight the tensions of housing integration. The painting is a visual representation of holding one’s breath – tense yet cautiously hopeful – and accurately captures the competing attitudes of the day.

With a career than spanned nearly six decades, Norman Rockwell was perfectly situated to witness perhaps the most rapidly changing era in American history. Rockwell’s changing depictions of race throughout his career directly mirror the larger cultural shifts that were happening at the time. Therefore, instead of reducing Rockwell to just one period of his career, it would be more accurate to view Rockwell as a symbol of 20th century American racial progress.

All Saturday Evening Post covers are from the Walt Reed Illustration Archive. To see more of Rockwell’s work with the Saturday Evening Post, schedule an appointment with the Douglas B. Dowd Modern Graphic History Library.

Image Sources

About the Author

Abisola Jegede is currently an undergraduate at Washington University, pursuing a degree in American Culture Studies with a concentration in the Construction of Race and Ethnicity in American Life. Her anticipated graduation date is December 2016.