ACLU-MO History Spotlight: School Desegregation

Ending Segregated Education

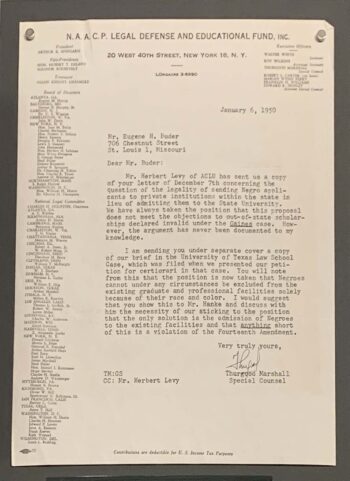

Starting in the 1940s, the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee began working with the local NAACP and Urban League chapters on civil rights efforts. This followed the pattern established by Roger Baldwin in founding the ACLU, ensuring that work on “inter-racial questions” was done in coordination with African American-led organizations. These early efforts focused mostly on reforms in criminal justice and segregated housing.

By the late 1940s and early 1950s, these efforts expanded to address the growing movement toward ending segregated schools.

Speaking Out

On October 15, 1948, St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee executive secretary Eugene Buder spoke to the Missouri House of Representatives’ Equal Rights Committee. He began simply: “Equal rights mean the same thing as equal protection of the laws… But education in Missouri is not equal.”

Then Buder laid out facts drawn from the annual reports of the St. Louis Board of Education:

“In the 92 white elementary schools there are 46 libraries; in the 26 Negro elementary schools there are three libraries (Report 1946-47, p.110).

Exclusive of maintenance and fixed charges, the Board of Education spends per year for the education of Negro elementary pupils on average $20.00 less per pupil than it spends on white elementary pupils (Report 1946-47 p. 190)

The average amount spent by the Board of Education per year for a white high school pupil is $219.77,… while the average amount the Board of Education spends on its Negro high school pupils per year is $177.09 (Report 1946-47, p.190)…”

Eugene Buder, Oct. 15, 1948

A Study of Race Inequalities

Many of these observations were subsequently published in a full report that the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee helped compile. Written by John J. Kessler, the 1950 report The St. Louis Public Schools: A Study of Race Inequalities also includes a broader “review of educational opportunities for White and Negro students in Missouri” with sections on discrimination by private schools and in higher education.

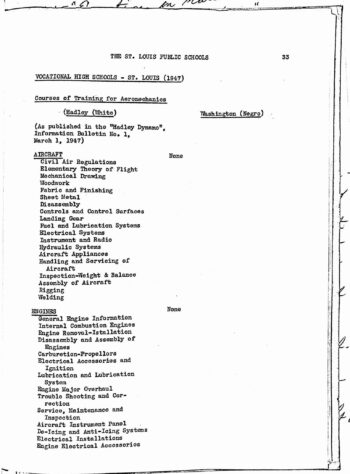

Page after page in the report offered concrete examples of how vastly unequal education was in St. Louis. For instance:

- Adult Education in 1947 — Hadley, for white students, had five auto-mechanic, eight graphic-art, four electrical, and nine business programs. At Washington High School for African-American students, only “barbering and power sewing” were offered, with all others ended for lack of space. (page 35)

- High school technical programs in 1947 — Hadley, for white students, had 19 aircraft and 14 engineering programs. Washington high school for African American students: none. (page 33, pictured below)

The report also considered the location of public schools for African-American students, noting that African-American families in the south portion of the city had no high school nearby, and as a result, if they wished to have opportunities for their children, their most readily available option would be moving north.

Today this map and report are but one of many pieces of historic evidence shining a light on St. Louis’ current demographic split between African Americans and whites along a north/south divide.

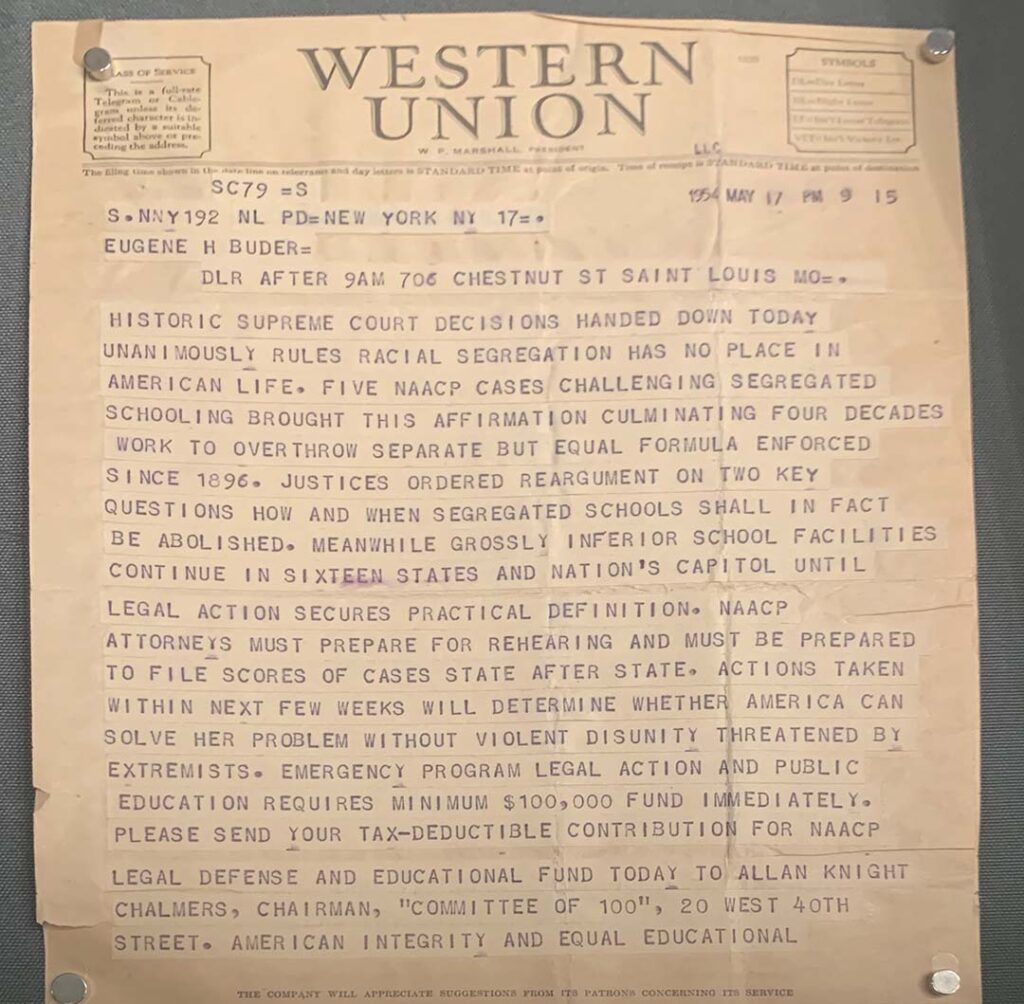

Brown v. Board, 1954

The Supreme Court ruling known as Brown v Board ended the legality of segregated education in 1954, but really it marked the start of work to implement this desegregation in Missouri. It was work the St. Louis Civil Liberties Committee would embrace then and continue to fight for now.

From ACLU-MO Records (wua00355) series 1, subseries 2, box 4.

More

- Colin Gordon, Citizen Brown: Race, Democracy, and Inequality in the St. Louis Suburbs (University of Chicago Press, 2019) [ebook available with WU Key]

- Citizen Brown: Race, Democracy, and Inequality in the St. Louis Suburbs companion website [open access online]

- For the Sake of All, Segregation in St. Louis: Dismantling the Divide (2018).

- Lloyd Gaines and the 1938 case Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, a key case about segregated higher education

- Gerald W. Heaney and Susan Uchitelle. Unending Struggle: The Long Road to an Equal Education in St. Louis. University of Nebraska Press, 2004.

- David Roediger, “What’s Wrong with These Pictures? Race, Narratives of Admission, and the Liberal Self-Representations of Historically White Colleges and Universities,” 18 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 203 (2005), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol18/iss1/9

ACLU-MO @ 100

This post is part of a series in recognition of the American Civil Liberties Union of Missouri’s centennial year (1920-2020). Read more stories at the following link: ACLU-MO @100 in Our News

If you have a question about this post or other topics related to St. Louis history, I can be reached at mrectenwald@wustl.edu or on Twitter: @mrectenwald

![A three-hole-punched slip of paper with a hand-drawn map and a typewritten key. The map shows St. Louis west of the Mississippi River with Forest Park designated as the western-most boundary, the cemeteries the northernmost; Tower Grove and Carondelet Parks are indicated as well. The typed key has numbers 1-4 denoting Public Schools and the sole letter, N, indicating African-American communities in South St. Louis. The schools are all clustered between Forest Park and the Mississippi River, a distance of approximately six miles according to the map's key. The map is further titled "[African-American] community in St. Louis and [indecipherable] available schools.](https://library.wustl.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ACLUMO-s6b10-1950p22-350x459.jpg)